Lake effect: Four big Erie Hack ideas that can help keep our lake Great

As the Cuyahoga River draws closer to a momentous milestone with the Cuyahoga50 celebration on June 22, Lake Erie is also having its time in the sun.

On Thursday, June 20, nine teams from across the Great Lakes region will gather in Cleveland to compete in the finals for Erie Hack 2.0—an innovation challenge spearheaded by Cleveland Water Alliance. The data and engineering competition brings together tech types, water experts, and high school/college students to identify smart solutions to Lake Erie's most pressing problems.

On Thursday, June 20, nine teams from across the Great Lakes region will gather in Cleveland to compete in the finals for Erie Hack 2.0—an innovation challenge spearheaded by Cleveland Water Alliance. The data and engineering competition brings together tech types, water experts, and high school/college students to identify smart solutions to Lake Erie's most pressing problems.

Even more awesome? Four of the nine finalists are from Greater Cleveland. Meet the Cleveland folks who will be taking the stage at Erie Hack 2.0 and find out how their big ideas are making waves for Lake Erie's future.

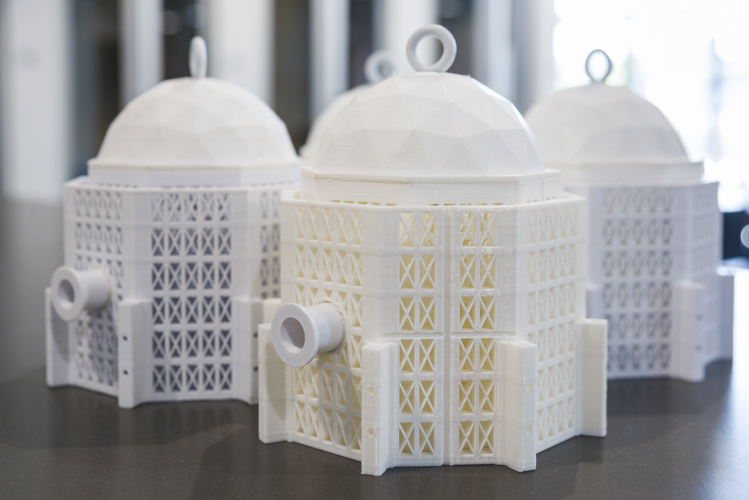

TACSO

With more than 300,000 geodesic domes around the world—from Epcot Center to Chile’s EcoCamp Patagonia hotel—Thomas Zung has made an indelible mark on the world of architecture, and now Zung wants to do the same for Lake Erie.

As one of the three principals for Buckminster Fuller, Sadao & Zung Architects. Zung was an integral part of the firm that popularized the geodesic dome concept. That concept is the inspiration for Zung’s Erie Hack project: TACSO (Trap and Contain Stormwater Objects), a octagon-shaped, cage-like structure that catches stormwater debris before it hits the lake.

As one of the three principals for Buckminster Fuller, Sadao & Zung Architects. Zung was an integral part of the firm that popularized the geodesic dome concept. That concept is the inspiration for Zung’s Erie Hack project: TACSO (Trap and Contain Stormwater Objects), a octagon-shaped, cage-like structure that catches stormwater debris before it hits the lake.

“Our motto is, ‘Let’s trap that crap,’” jokes Zung, who says this is one of four inventions he’s currently developing.

According to Zung, there are 86 lakefront communities in Ohio that do not have a combined sewer overflow system—leaving those areas of the lake susceptible to “plastic bottles, dead animals, condoms, and a lot of needles,” says Zung. “God bless NEORSD for doing these big digs, but what happens to [help] the smaller communities? That’s what compelled me to do this invention.”

The TACSO structures will be eight feet in diameter and nine feet high, with the capacity to hold half a ton before being emptied. As a nod to Northeast Ohio manufacturing, Zung plans to create the domes from polymer rather than metal.

Currently, Zung is working with two local students to realize his vision: Case Western Reserve University engineering student Joel Hauerwas and Cleveland Institute of Art student Jason Taft. “I’m 86 years old, and I wanted this [to be a gift] for the future,” says Zung. “The future is students.”

He’s hopeful that innovations such as TACSO can also help Cleveland continue to evolve in the right direction. Says Zung, “What can we do to facilitate the change from being an industrial city to an environmental city? TACSO is part of that.”

S4

Anyone who’s tried to swim at Cleveland’s various beaches during the summer knows these three dirty words: “harmful algal blooms.” 2019’s forecast looks no different—with the National Weather Service projecting a severity of 7 or higher (a number “much greater” than 2018).

That’s where S4’s Erie Hack project comes in. Since harmful algal blooms are primarily caused by agricultural runoff, S4’s project would stop runoff at the source via a robotic device. This automated device would use reflective light to analyze nutrient concentrations in soil—namely phosphorus and nitrogen (both culprits in algal blooms).

That’s where S4’s Erie Hack project comes in. Since harmful algal blooms are primarily caused by agricultural runoff, S4’s project would stop runoff at the source via a robotic device. This automated device would use reflective light to analyze nutrient concentrations in soil—namely phosphorus and nitrogen (both culprits in algal blooms).

That information would then be used to create a 3D map pinpointing the most effective types of drainage ditches and buffer zones—and allowing farmers to customize as necessary to minimize damaging runoff and keep the nutrients where they belong. (Win-win!)

“What’s most effective in one place may be different somewhere else due to factors like topography and crop usage,” explains David Perry, head of S4 and Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at the University of Akron.

The S4 team already has interesting proof-of-concept in other realms, as their device has been in use for archaeology teams on Native American sites, and they’re also finding an array of forensic uses because the device can detect clandestine burials and chemical residue underground.

Perry thinks that applying their device to helping divert runoff from Lake Erie could “potentially have the biggest impact” of all its uses, citing Governor Mike DeWine’s new H2Ohio program which will devote funding to improving state water quality.

“[In theory], the Ohio EPA could be a primary customer that ends up paying for these devices,” says Perry. “The H2Ohio program will be addressing water quality issues in Ohio, particularly Lake Erie, and algal blooms are high on that list.”

Cleveland AI

A Cleveland-based meetup group for artificial intelligence experts has spun off into a mini think-tank for improving Lake Erie, with five people from Cleveland AI teaming up for Erie Hack.

Their big idea? A faster, more nimble way to measure toxins in Lake Erie before the water reaches treatment facilities. According to Cleveland AI’s Jason Mancuso, the

Their big idea? A faster, more nimble way to measure toxins in Lake Erie before the water reaches treatment facilities. According to Cleveland AI’s Jason Mancuso, the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) currently measures toxin values with large aquatic machines that extract water for testing and then produce an image showing toxin concentrations.

“[That process] requires a human to sift through the images and label them in a certain way,” says Mancuso. “What we’re doing is automating that process without a human in the loop. The information can get turned around faster.”

Why does that matter? Mancuso says it can provide a faster reaction time as a game-changer for water treatment facilities. “[With the current approach], by the time the toxin value is figured out based on image technique, the water has already arrived at the treatment facility and it’s too late for the toxin count to be of value,” says Mancuso. “This automates and expedites the process.”

Eventually, Mancuso hopes to combine the technique with drone and satellite imagery to help widen the geographical capability and cut costs. “We want to create a better solution than these super-expensive machines the government has right now,” says Mancuso. “Our ultimate goal would be to take this technique and open-source it for researchers and academics and the government to use the technology beyond Lake Erie.”

Erie-Duction

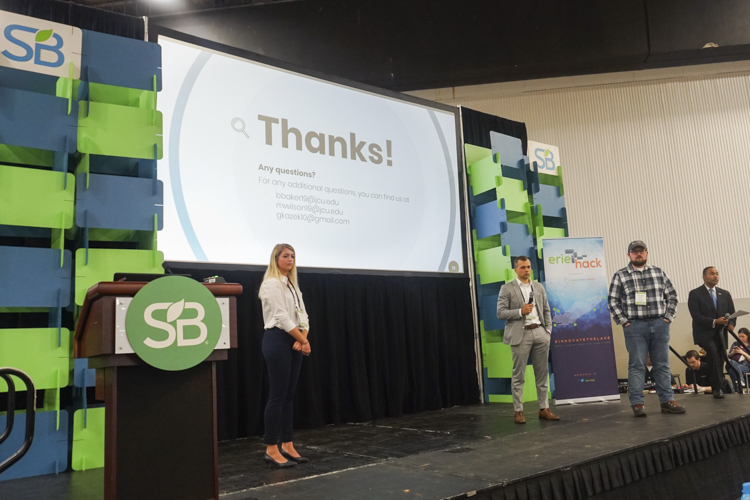

What happens when you combine three recent John Carroll University graduates, a passion for Lake Erie, and a unique type of natural clay earth pigment called ochre? A new solution for keeping algal blooms at bay.

Gus Kazek, Brooke Baker, and Matthew Wilson have joined forces to create Erie-Duction, a new method that incorporates ochre pigment into farm drainage tile systems to help absorb phosphorus while letting the water seep through.

Gus Kazek, Brooke Baker, and Matthew Wilson have joined forces to create Erie-Duction, a new method that incorporates ochre pigment into farm drainage tile systems to help absorb phosphorus while letting the water seep through.

In fact, Kazek estimates this method can reduce phosphorus floating in the Great Lakes by 20 percent, or “more specifally, the Maumee River, which accounts for a large portion of algal blooms,” says Kazek. “We plan to use our product to help mitigate the phosphorus before it enters the tributary and eventually into Lake Erie.”

Kazek believes this could not only benefit the Great Lakes, but also provide cost-effectiveness and efficiency for farmers—allowing them to reuse the phosphorus caught by the ochre to fertilize their crops.

For Kazek, he thinks all of these advances are coming at a critical time for Lake Erie's health, and he's grateful for opportunities like Erie Hack that can help further them.

"The big tipping point [with algal blooms] was in 2014 when Toledo was unable to drink water for three days," says Kazek. "It's like the Cuyahoga River—it caught on fire 15 times, but the 15th time triggered a whole environmental movement. People are paying attention now."