Giving food scraps a new purpose

About one-third of all the world’s food supply -- approximately 1.3 billion tons -- becomes waste every year. In America alone, 33 million tons of wasted food ends up in a landfill annually.

“The problem is assigning value to what is much more cheaply thrown away,” Dan Brown, co-founder of Rust Belt Riders, a Cleveland organic waste removal company, explains.

This summer Brown and partner Michael Robinson did in fact assign a dollar value to food scraps at the Gordon Square farmers’ market every Wednesday. At the Rust Belt Riders kiosk, shoppers were reimbursed with $1 in market credit for every two pounds of food waste they brought in. Shoppers could earn up to $10 in credits.

Michael Robinson and Dan Brown of Rust Belt Riders at the Rid-All composting bins

Michael Robinson and Dan Brown of Rust Belt Riders at the Rid-All composting bins

Rust Belt Riders successfully collected 2,000 pounds of fruit and vegetable trimmings for composting at community gardens in Gordon Square. All of the food waste collected by their commercial clients goes to Rid-All Green Partnership, an urban farm in Cleveland's Kinsman neighborhood. The Riders hope to expand the program to additional area farmers’ markets in 2016.

“People are very interested in a stall where no one is selling anything,” Brown says of his space at the market this summer, but quickly adds that aggressively educating shoppers about the food cycle and food waste was key to getting people to bring in what they would normally throw out.

The concept of saving compostable food from landfills, and instead putting it to good use, is a notion that is starting to catch on in Northeast Ohio.

An Education in food waste

Brown and many others from the area interested in diverting food waste from landfills came together last weekend at CWRU’s Squire Valleevue Farm for Food Waste: A Northeast Ohio Conversation, an event funded by North Central Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (NCR-SARE).

Brown stressed at the event that the road to reducing waste begins with education. “There needs to be education because not everyone thinks about food waste,” he says. “People need to know that it’s not like the garbage fairy comes and it disappears.”

According to Brown, the EPA estimates that as much as 24 percent of all household waste is compostable. Although recycling food waste through composting is a more expensive and more complicated than simply throwing it away, there is a growing interest as people increasingly focus on the food cycle as a whole.

Compost mound at Case Western Reserve University Squire Valleevue Farm

Compost mound at Case Western Reserve University Squire Valleevue Farm

For the last year Rust Belt Riders has transported food waste from farmers’ markets and restaurants in Cleveland for composting. In the beginning the company used only bikes and collected food waste from residential customers. But they are now focusing their efforts on commercial customers mainly restaurants.

“We still don’t pretend to compete with traditional waste management,” Brown says.

Brown thinks that the key lies in City of Cleveland taking charge by creating a mandate to reduce food waste – similar to what cities like Boston, Seattle, San Francisco and Austin have done recently.

“It is so cheap to throw things away,” Brown explains. “But people are beginning to care where the food is going and the consequences.”

Feed pigs, not the landfills

Abbe Turner, owner of Kent’s Lucky Penny Creamery and the Food Waste event coordinator, was just looking for something to do with the whey left over as a by-product from her farm’s cheese production when she decided to put together the November event.

After some research, Turner bought 10 pigs to help process, or consume, the whey that larger farms ‘evaporate’ using a high-powered, very expensive machine.

“There is a long tradition of using pigs to process whey,” Turner explains adding that her solution got her thinking about how much easier it is to traditionally dispose of something as nutrient rich as whey rather than find another solution.

“There are a myriad problems with dealing with food waste and they are interwoven,” Turner says. “Americans have a causal relationship with throwing away food.

“Food waste makes up 40 percent of modern landfills and two-thirds of that waste comes from people’s refrigerators,” Turner continues. “We are over-producing food in the U.S. It exceeds what is consumed in a timely fashion.”

An American family of four throws away $1,600 in food every year. As a country the United States throws out an equivalent of $165 billion in food annually, which costs $750 million to dispose of, according to a 2012 Natural Resources Defense Council report.

The problem lies in the extra cost or effort in re-directing food waste out of the landfill. Instead, consumers need to buy more often and not buy too much.

Composting, redirecting farm by-products to feed animals or fertilize fields requires a lot of logistics, Turner cautions. “It is one or more steps than just throwing it in the dumpster.”

Innovative concepts on CWRU campus

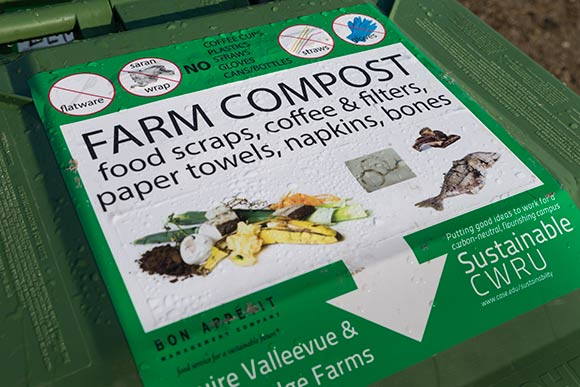

As the marketing manager for Bon Appetit Management Company, Beth Kretschmar is well aware of the extra work that goes into reducing waste and repurposing food that would otherwise not be consumed.

Also a speaker at the Food Waste event, Kretschmar saw it as a chance to share ideas and to find and form new partnerships or even a chance meeting in an effort tackle food waste issues.

Since 2004 Bon Appetit has provided food for students on the CWRU campus and as part of a national strategy to become more sustainable, the company purchases 24 to 25 percent of local food from sources within 150 miles of the dining facilities.

“Considering winter in Ohio that is pretty good,” Kretschmar, says.

Food waste from Bon Appetite’s kitchens and dining rooms are picked up weekly and transported to Squire Valleevue Farm. The farm receives 500 gallons of food scraps per week and creates 30 to 40 cubic yards of compost that is spread on the fields once a year.

“As of October 2015 Bon Appetite has taken 2,317 gallons to compost,” Kretshmar says.

The Bon Appetit kitchen also repurposes vegetable scraps for veggie stock and makes food to-order to reduce redundancy and waste. Pre-made food that has not been sold and maintains a current sell-by date is donated to local food banks.

Conversations spark new ideas

Due to EPA regulations, the farm can only receive food waste from university sources. “We have to say ‘no’ or else we would have to register as a waste facility,” Chris Bond, farm food program coordinator at CWRU and one of the hosts of the Food Waste event explains.

The 30 to 40 yards only covers about one-quarter of the three acres used to grow produce. “It is a small amount and not enough for the acres of food we grow,” Bond says.

Chris Bond, Farm Horticulturist at CWRU Squire Valleevue Farm checks the waste brought in for composting

Chris Bond, Farm Horticulturist at CWRU Squire Valleevue Farm checks the waste brought in for composting

Bond says the farm could use more food waste -- it’s a just a matter of having more compost material. But there is less composting material available in summer since school is out of session.

“It took five years to figure it all out and there are still problems,” Bond says. If there is any weak link it is in the chain and logistics. The problem is getting from A to B.”

Bond says he believes that commercial composting is catching on in Cleveland. “Supply is there and the demand is there,” he says. “You would think it would be easy.”

Conversations and meetings like the Food Waste are an important step changing the way the city looks at food waste. From educating people about the ill effects of sending food waste to a landfill to the misconceptions regarding composting, changing a system people are so used to will take time.

“Now more than ever people are concerned with where their food is coming from, they should also be concerned with where it goes,” Brown says. “Complete that loop and everyone wins.”