reduce, recycle, refurbish, repeat: how cle is becoming a leader in deconstruction

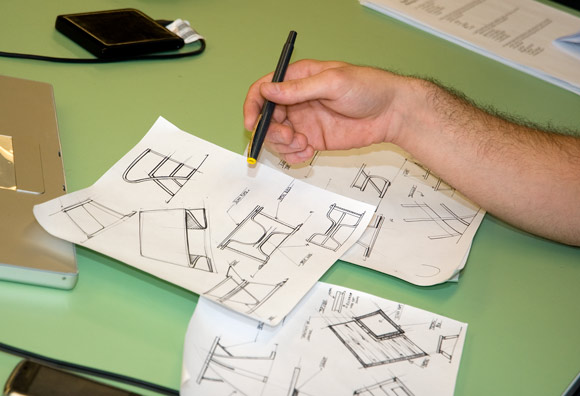

Jesse Hill is working quietly at his station, tucked away in a corner of the cluttered and bustling furniture design center at Cleveland Institute of Art, when Daniel Cuffaro approaches and asks Hill to show off his "magic box."

Roughly four feet by four feet, the box is constructed of wood. Some of the sides sport panels of fabric that resemble office-cubicle wallcovering. Hill wheels the box into an open area and begins taking it apart. Lifting the top off reveals a set of legs -- it's a small table. Next, he pulls out some planks that quickly assemble into a book shelf. What remains of the box now serves as a computer desk. The entire transformation, from nondescript box to personal office suite, takes about a minute.

As Hill reassembles the pieces, Cuffaro, head of the Industrial Design department at CIA, explains the backstory. The box is the result of a recent design project in which students were asked to create multi-function, easily stored pieces for various working, living and lounging spaces around campus.

Hill's box, Cuffaro notes, was constructed entirely out of wood salvaged from a condemned Cleveland house. So were many of the other desks, tables and chairs designed and built by CIA students, who more and more must be equally deft with both state-of-the-art design software and centuries-old lumber. In fact, today's design students are part of a broader experiment: an attempt to build a new industry out of the bones exposed by the foreclosure crisis.

Furniture making is taking off in Northeast Ohio. According to Cuffaro, there are roughly 400 furniture-related businesses in the region, and their work is getting noticed. The various lines produced by Jason Radcliffe's Forty Four Steel are selling well in New York. Designer Joe Ribic, owner of Willoughby-based Objeti, won the Editor's Award at this year's International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York. The second annual Cleve-centric design showcase F*SHO, held this past September, attracted three times as many visitors as the first installment. Plans already are under way for additional events in advance of next year's show. Designers, builders and support organizations are finding each other, sharing resources and ideas, and making noise.

All that would be cool enough in a region better known for the industries it has lost. But there's much more to the story. In a spirit reminiscent of progressive outposts like Seattle, Cleveland is becoming a national leader in deconstruction, a movement that treats vacant homes across the region not as an eyesore but a post-natural resource.

"We don't want to be another New York," says P.J. Doran of A Piece of Cleveland. "We want to be Cleveland."

Civic pride is at the heart of APOC, the furniture company Doran, Chris Kious and Aaron Gogolin launched in 2008. Relying on expertise culled from years in housing -- Doran and Gogolin in construction, Kious in community development -- the team systematically dismantles condemned houses. Working from the roof down, they harvest every plank, joist, beam and floorboard that appears reusable. The rescued and resurfaced lumber is then crafted into tables and benches, cutting boards and candlesticks. Each piece comes with a "rebirth certificate," which details the source of that particular material.

That unique backstory is definitely a selling point, says Doran. He knows of items purchased as gifts specifically to ship to Cleveland exiles. Those rebirth certificates also send a subtle message: This is something Cleveland can do that New York cannot.

"There's such a wealth of materials here," says Michael McMillan of North End Woodworks and Furniture, located in the Detroit Shoreway neighborhood. At F*SHO, he says, a woman approached him to say that the wood in one of his pieces came from her old house in Cleveland Heights.

Former professional musician Freddy Hill, owner of Bomb Factory Furniture, builds mostly high-end pieces out of walnut, but he says that Doran inspired him to add a line made from reclaimed wood. He recently acquired materials from a demolished bowling alley in Illinois, thanks to a tip from a friend who mentioned in passing that it was available. "You're definitely selling the story," he says. "This wood used to be somebody's roof, or somebody's front porch."

History is one reason the Cleveland Foundation is supporting deconstruction, but the future is a much larger factor. Lillian Kuri, program director for architecture, urban design and sustainable development, says the foundation has been funding and promoting "decon" for several years because of the sustainability element and the potential for job creation.

"We can decide that we're no longer going to dump 5,000 homes' worth of material into a landfill," Kuri explains. "It's about a continuum, and creating a whole new industry here." And that's where the Cleveland Institute of Art comes in. "CIA has stepped up in a tremendous way, saying, 'We should be part of the solution.'"

Here's how the ambitious plan will work: CIA is building new classroom and studio facilities on Euclid Avenue, in University Circle. Studio furniture for the facility will be designed by students and built by APOC out of reclaimed wood. Cleveland Foundation is offering financial support, says Cuffaro, with the intent of jump-starting a new local industry. If a fledgling operation like APOC can scale up to meet the needs of a large client like CIA, then the possibilities are endless. "Cleveland's version of Ikea," is how Doran puts it. "Great design for the masses" that is also affordable.

Deconstructing a house costs more than demolishing it, Cuffaro explains -- about $12,000 per house versus $8,000 to level it and haul it away. But decon employs more workers, sends less waste to landfills, and saves money for those who utilize salvaged materials.

"There's no such thing as waste," Doran says, "just resources mismanaged."

Like what you see? Subscribe to receive Fresh Water, Cleveland's fresh new e-zine, delivered weekly to your inbox.

- Cabinet made by A Piece of Cleveland