How Gordon Park could become Cleveland's 'Edgewater East'

Slowly but surely, the pieces are falling into place to reassemble the two sizeable halves of historic Gordon Park. To do so, plans feature the long-desired relocation of the Shoreway further south to open up the lakefront for prime recreational and residential development.

On Friday, Nov. 1, at 8 a.m. at Merwin’s Wharf, the Green Ribbon Coalition will conclude its 2019 Possibilities Forum series with “Bold Visions,” a panel discussion about turning Gordon Park into Cleveland's "Edgewater East" and building a lakefront trail across the county. The latter topic became real Oct. 17, when Cuyahoga County announced plans for a Lake Erie Trail to connect boardwalks, paths and trails across the lakefront from Bay Village to Euclid.

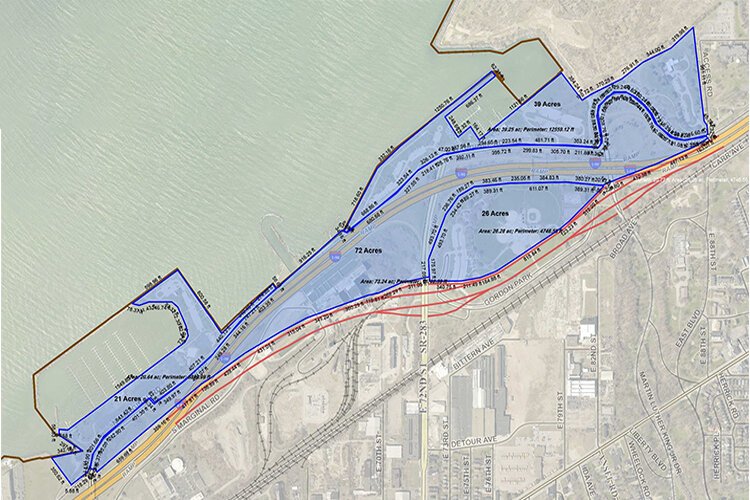

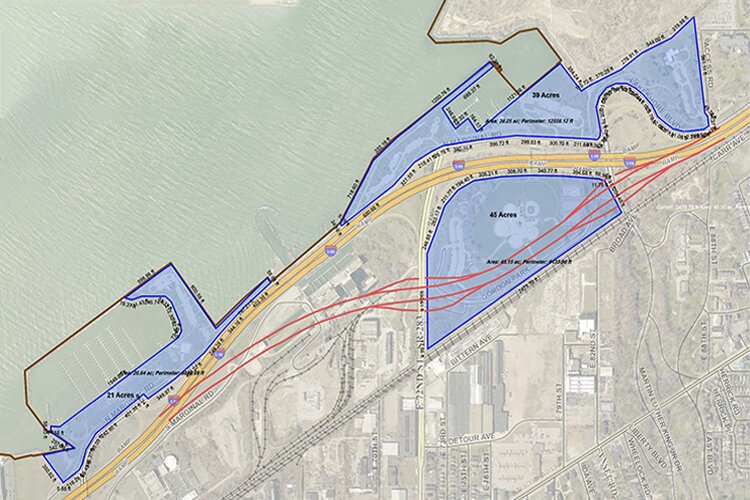

Gordon Park proposed acreage“The Lake Erie Trail and Gordon Park Expansion are transformational projects with huge economic potential for Cleveland and the region,” says Dick Clough, who runs the Green Ribbon Coalition and moderates the panel discussions. “The Gordon Park expansion will function as the cornerstone for Cleveland’s next big economic development zone, and perhaps the biggest.”

Gordon Park proposed acreage“The Lake Erie Trail and Gordon Park Expansion are transformational projects with huge economic potential for Cleveland and the region,” says Dick Clough, who runs the Green Ribbon Coalition and moderates the panel discussions. “The Gordon Park expansion will function as the cornerstone for Cleveland’s next big economic development zone, and perhaps the biggest.”

Opened as a natural respite for the public in 1893 at a time when downtown Cleveland burned as a noisy, smoke-belching industrial hotbed, Gordon Park was split in two in 1941 with the expansion of I-90 eastward from the western edge of the park to East 140th Street in Euclid. An expedient path for cross-town and cross-country motorists, the interstate created a barrier between the lake and downtown and the eastern neighborhoods that urban planners have wrung their hands over ever since. Today, the dream of a citizenry reunited with the waterfront attractions of Lake Erie’s shore continues to gain traction.

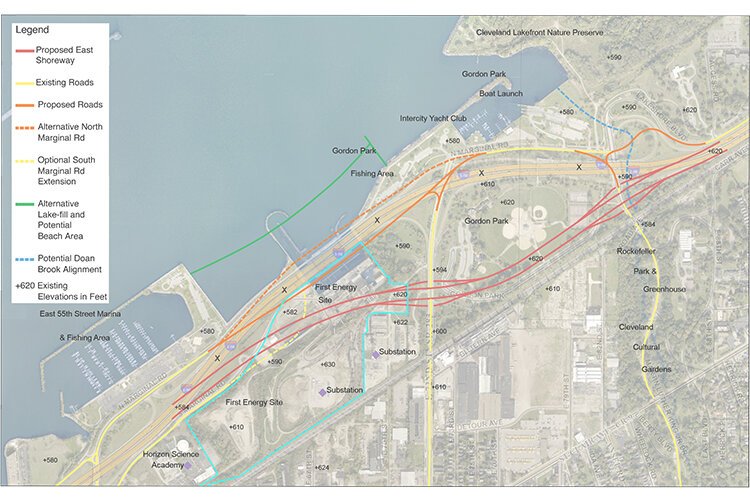

Bob Gardin, one of the Green Ribbon Coalition forum panelists and vice board chairman of lakefront projects for the coalition, has been tracking the relocation of the Shoreway and concomitant reconnection and revitalizing of Gordon Park for almost 20 years. The turning point, he says, came in the early 2000s, when Cleveland Tomorrow, now the Greater Cleveland Partnership, proposed “flipping” the Shoreway south behind the railroad tracks that run parallel to I-90.

Gordon Park existing acreageFirstEnergy’s more recent announcement of the closing of its 104-year-old coal-fired power plant in 2015 further fueled the potential to relocate the highway and redevelop the plant’s ideal–albeit brownfield in need of costly environmental abatement–lake shore location.

Gordon Park existing acreageFirstEnergy’s more recent announcement of the closing of its 104-year-old coal-fired power plant in 2015 further fueled the potential to relocate the highway and redevelop the plant’s ideal–albeit brownfield in need of costly environmental abatement–lake shore location.

Gardin and his colleagues began doing extensive research to explore the possibilities that had become available. He realized that although the plant was deactivated, the substations nearby would need to remain active, so he began to develop a different alignment that could work for the interstate roadway relocation.

“I started to look at what we could do considering the infrastructure that needed to remain,” says Gardin, who also serves as executive director of Big Creek Connects. “That’s how we came up with our first concept plans and narrative document that we published on March 10, 2017.” They updated the plan later that year and just completed another revision in early October that is now available online.

Gardin cites numerous benefits of this project, including the following:

- Pulling the Shoreway away from the shoreline would reduce the amount of water and ice that make road conditions slick during rainstorms and snowstorms, as confirmed by the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, Greater Cleveland’s transportation and environmental planning agency.

- The upper and lower halves of historic Gordon Park could be reconnected. The upper park is managed by the city of Cleveland Parks Division, and the lower half by the Cleveland Metroparks. Gardin estimates that the combined park space would total about 160 acres, which would exceed Edgewater Park’s 147 acres, and that doesn’t include the 188-acre Lakefront Nature Preserve, or Dike 14, connected to Gordon Park’s lower half.

- The north and south marginal roads could be connected to create a true lakefront road that would no longer require getting on and off I-90 to get to the park from downtown.

- Cleveland lacks a true beach on its East Side between downtown and the Metroparks’ Euclid Creek Reservation. This realignment would enable the building of a substantial beachhead, Gardin says.

- Doan Brook, which runs openly through the Cleveland Cultural Gardens along Martin Luther King Boulevard but goes underground as it approaches Gordon Park, could be daylighted near Dike 14, where it empties into Lake Erie.

- One of the most significant benefits of the relocation of I-90, according to Gardin, Clough and others, would be the potential economic development for the adjoining neighborhoods. Gardin believes the development occurring on the West Side from about West 58th Street to West Boulevard along Detroit Road and north with Battery Park and Gordon Square serves as a model that could be replicated.

“If you flip that over to East 55th Street and East Boulevard, you would have basically the same infrastructure, but you also have a lot of empty parcels like the old White Motors site between East 72nd Street and MLK,” he says. “That could become the Battery Park of the East Side and serve as a huge economic driver for those surrounding neighborhoods, particularly St. Clair-Superior and Glenville.”

The two concepts Gardin developed include possible tunneling under the railroad tracks to provide direct access for housing and commercial projects, as was also done near West 65th Street. Most importantly, unlike some of the Green Ribbon Coalition’s other proposed lakefront reconnection and development projects such as building a landbridge extension of Mall C or closing or redeveloping Burke Lakefront Airport, he believes it could happen reasonably quickly. He has seen buy-in and support from the city of Cleveland, NOACA and others key players.

A freeway runs through it

Another panelist, Jeff Homans, vice president, Division of Buildings and Places, AECOM, Cleveland, knows intimately what can and can’t be moved along the shoreline and how Gordon Park could be expanded. In recent decades, Homans led studies and development of plans to relocate the Port Authority facilities that were not implemented.

“The universal truth of that area of our lakefront is that we have a freeway that separates the neighborhoods and the people from the waterfront,” he says. “We would all like to see that remedied.”

Allisson Lukacsy-Love will focus on discussing the Euclid Waterfront Improvements Plan that she oversees in her role as community projects manager for the city of Euclid’s Department of Planning and Development.

“This project started about 10 years ago because our slogan is that we are The Lakefront City,” she says. “We have just under 50,000 residents, but very few of them actually have access to our regional greatest natural asset because 90% of Euclid’s shoreline is privatized, and we have two public parks.”

On Dec. 16, with the completion of a $6.8 million construction phase started last November, Euclid plans to open the first part of the trail. That section represents roughly half of the final trail. The estimated total cost of the project is $12 million. Euclid recently received the final approval for a $2.67 million fund from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, because of the shore erosion repair and protection required to build part of the trail; they will break ground on that in 2020. The city is working to raise the additional funding required.

Nearly 100 stakeholders participated in the negotiation process, and the majority were able to achieve easement agreements so that the city could build and maintain the trail, but it will remain the private residents’ property. They did acquire some parcels, and K&D Co., one of the largest apartment managers in Ohio, donated land to Euclid for the project.

“We’ve been fortunate to receive interest across the Great Lakes region and nationally with this project because of the unique public and private partnerships that have gone into making this a reality,” Lukacsy-Love says.

About the Author: Christopher Johnston

Christopher Johnston has published more than 3,000 articles in publications such as American Theatre, Christian Science Monitor, Credit.com, History Magazine, The Plain Dealer, Progressive Architecture, Scientific American and Time.com. He was a stringer for The New York Times for eight years. He served as a contributing editor for Inside Business for more than six years, and he was a contributing editor for Cleveland Enterprise for more than ten years. He teaches playwriting and creative nonfiction workshops at