Boomers are now contemplating retirement amid uncertain economic times

Paul Hadley turns 70 next month, an agewhen most Americans are contemplating retirement, if they have not hung up their work boots already.

Hadley has spent the last few years downsizing his ironwork business, where he sketches and builds custom pieces for interior designers and contractors. Downscaling efforts aside, the lifelong entrepreneur is still contemplating when he will officially join the ranks of retired Americans—a figure that reached 48 million.

Though Hadley still works from a 1,000-square-foot space in Bedford Heights, his last employee left two years ago. Recent health issues, including major shoulder reconstruction, accelerated his retirement timeline.

Yet, the Lyndhurst resident can’t imagine himself spending the next months, years, and decades kicked back on the old Barcalounger reading the newspaper.

“I consider [metalworking] a profitable hobby—it’s kind of hard to sit around and do nothing,” says Hadley. “As I got closer to retirement, I talked to someone who said it’s like having six Saturdays and a Sunday every week. If you’re not doing anything, it’s kind of boring.”

Hadley’s story is reflected nationwide among fellow baby boomers—the generation born between 1946 and 1964. In recent years, these folks have put off retirement due to improved health, shifting industry patterns, and a decline in assets owing to a convergence of national emergencies.

Paul HadleyIn 2019, about 57% of Americans in their early 60s were still working—a jump of 11% compared to two decades earlier. Part of this shift can be attributed to an educated populace working longer in office jobs rather than in manual employment where physical limitations can hasten departure, says Jenny Hawkins, an assistant professor of economics at Case Western Reserve University.

“Those [education-based] skill sets are still valuable,” Hawkins says. “Also, having more education means people might be working in something that they’re passionate about without those physical demands.”

Simple economics are also keeping this demographic in the workforce longer, adds Hawkins. Boomers were in their 50s and early 60s when the economy first emerged from the Great Recession in 2009. Then came the one-two punch of COVID-19 pandemic and inflation, causing would-be retirees to question their golden-years financial needs.

“People were looking at how much they needed to live a certain way, then these different crises were laid on top of one another,” says Hawkins. “How much would COVID and other uncertainties impact those decisions?”

A complicated equation

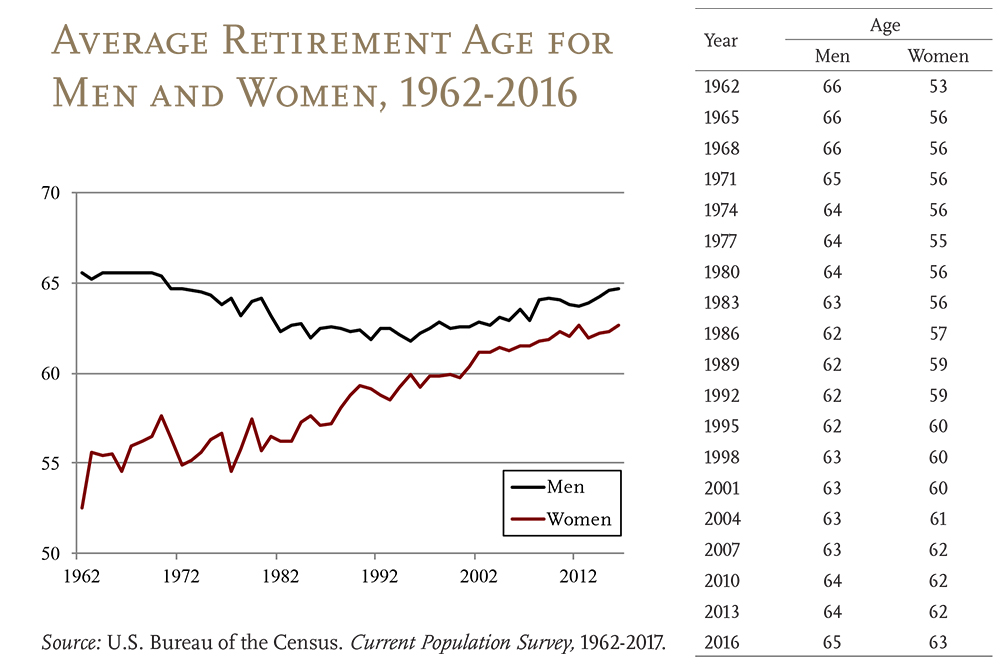

According to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, men are retiring at around age 64 ½, while women are exiting the labor ranks at 62 ½. Over the last 30 years, the retirement age for men has gone up one year each decade. Women have retired at a slower rate since 2011—a trend that slightly decreased from 2017 to 2021.

Even if negative factors such as age discrimination and poor health may motivate some people to retire sooner, life-cycle choices like delayed parenthood may be keeping people working longer, Hawkins notes.

JennyHawkins.JPGFurther complicating that retirement math is elevated wage growth derived from the ongoing structural labor shortage. Better pay could incentivize those near retirement to re-enter the workforce with hopes of building a larger nest egg.

“I’d argue that the most important factors keeping people from retiring are lack of savings combined with cost of living increases,” says Hawkins. “Social security benefits won’t cut it, so without enough savings for retirement, people must continue to work.”

Tom Jarecki, national head of financial planning at KeyBank, sees these trends among clients who had aimed to retire this year or next. Market volatility and uncertainty around inflation are two major factors driving people to delay those plans.

Economic fallout from the virus crisis is part of that equation as well, Jarecki says.

“Healthcare costs are not necessarily rising faster than before, but for so many families, the experience of seeing a loved one go through a serious case of COVID was a reminder that healthcare cost considerations in retirement are critically important,” Jarecki said in an email.

Tom_Jarecki.JPGA good financial plan

The aging population controlling what it can is perhaps the best advice Jarecki can give. That means saving money through increased 401k contributions, a Roth IRA, or a meticulous budget plan that allows you to sock away more funds.

“A good financial plan is only as good as the information we input,” Jarecki says. “So it starts with financial goals and priorities—both short-term and long-term. It requires us to understand how much we spend today, and how much we can afford to save. We need to consider investment risks and ensure we stick to the plan.”Hadley, the entrepreneur on the cusp of retirement, has long since paid off his house, while his wife, Carol, left the medical imaging field a few years ago. Pandemic stay-at-home orders allowed Hadley to continue working at his metal fabrication shop, even as he collaborated with a financial planner on a more restful future.

As some semblance of full-time retirement nears, Hadley is looking forward to extended family hangouts and summers of relaxing travel. Ideally, a stable stock market will fuel all his endeavors in the years ahead, he says.

“Some people have to work past retirement because of financial needs,” Hadley says. “But what everyone hopes for is to get to the point where they’re healthy enough to slow down and enjoy life.”