Meet the real-deal, long-time Old Brooklyn residents, whose stories matter more than ever.

Historical Society of Old Brooklyn

Historical Society of Old Brooklyn

Right now, members of the Historical Society of Old Brooklyn are busily preparing for the organization’s annual “Potluck Show-n-Tell” event in November—when local history buffs will get the chance to show off their favorite collectibles from the neighborhood. (In the past, totems have ranged from depression glass to a Mabel Footes opera cape to a Dr. Otto’s business sign to turn-of-the-century pharmacy prescriptions.)

Led by president Connie Ewazen, the HSOB is a dedicated bunch that has been meeting regularly since 1982—when a group of locals interested in forming a neighborhood historical society first met in the basement of the Glenn Restaurant on Pearl Road. Over the years, the group has taken on a number of ambitious initiatives in preserving Old Brooklyn’s legacy, including an intensive oral history gathering project resulting in two books.

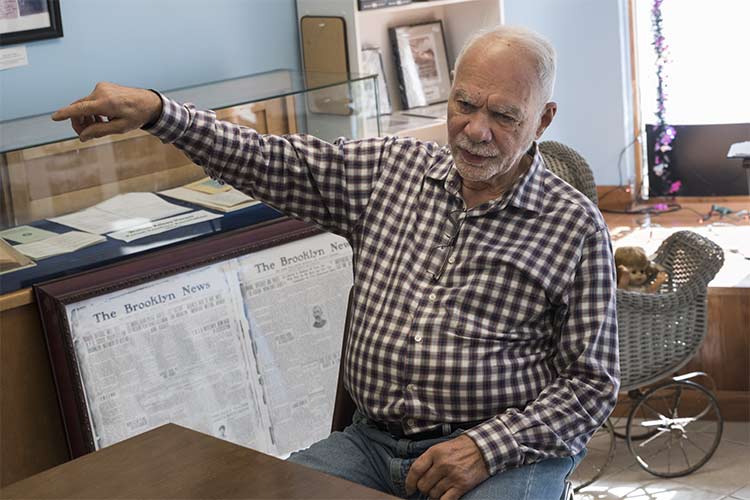

The heart of the operation is the tiny museum located at 3430 Memphis Ave., which has been open since 2016. The small but significant room plays host to a treasure trove of Old Brooklyn gems, from old James Rhodes High School yearbooks to framed copies of The Brooklyn News to a pram filled with baby dolls donated by an elderly resident.

“There was an old lady from the senior center who wanted to make sure her dolls would stay in Old Brooklyn when she was gone,” says Ewazen.

In light of the neighborhood’s momentum, Ewazen sees the society’s role as more pivotal than ever. “One of the objectives of the historical society is ensuring that, as the neighborhood flourishes and changes, the history continues to live on,” says Ewazen, who has been part of the group since 1986 (when the group became official).

Indeed, Old Brooklyn is in a period of immense change, but the rich legacy of the neighborhood is unlikely to be forgotten any time soon—and that’s in large part due to the hard work of the historical society. So we wondered: while the HSOB is busy telling Old Brooklyn’s story, who is telling their stories? We asked Ewazen to assemble a group of long-time HSOB participants so that they could share their own storied pasts, and their tales didn’t disappoint.

Riegelmayer-Kolodny homeThis Old House: Jill Riegelmayer-Kolodny

Riegelmayer-Kolodny homeThis Old House: Jill Riegelmayer-Kolodny

When any house is on the market for six years, it’s sure to attract attention—but for Jill Riegelmayer-Kolodny, the massive 18-room historic house on Schaaf Road was a constant source of curiosity. “I felt God was saving that house for me,” says Riegelmayer-Kolodny.

When Riegelmayer-Kolodny eventually bought the home, she became “obsessed” with learning more about its original tenants—scouring the fourth-floor attic of Pearl Road United Methodist Church (where the society’s archives were stored before the museum opened) for old articles from the Cleveland Press, death notices, and former editions of “Who’s Who in Cleveland.” She also found blueprints for the house, which were dated around 1925 and 1927.

What she learned was that the house was built by Samuel J. Webster, a renowned doctor who helped found Deaconess Hospital. (In fact, the same bricks were used for both buildings.) Webster’s medical practice included applying leeches, using acupuncture, and treating typhoid fever by immersing patients in ice-cold baths; he also delivered more than 500 babies during his career.

Riegelmayer-Kolodny also learned that Webster practiced out of his home, which explained why there were two entrances (one for patients and one for personal use).

“He chose that location for the house because he wanted to be close to the hospital; the western side of Schaaf was then known as Doctor’s Row,” explains Riegelmayer-Kolodny. “Webster used to start his office hours around 5:30 or 6 a.m. because the whole neighborhood was made up of greenhouses. He would get up early to take care of the farmers and go by horse-and-buggy to make house calls.”

Riegelmayer-Kolodny continued her quest for information by tracking down Webster’s great nieces and nephews, as well as finding Webster’s former scalpels and equipment at the Dittrick Museum of Medical History. Some of the relics can even be found within the home, such as the 1896 diploma that still hangs above the fireplace in the office, and the sitting room that was once Webster’s waiting room.

“I’ve always been intrigued by old homes, and the fact that I have one to live in with a great history is just phenomenal,” says Riegelmayer-Kolodny.

Vern ReckerSacred Ground: Vern Recker

Vern ReckerSacred Ground: Vern Recker

Sporting a curly handlebar mustache, a Bolo tie with an Ohio-shaped gemstone, and a trucker hat that reads “U.S. Navy Seabees,” Vern Recker just looks like a man with stories to tell—and he doesn’t disappoint. The 75-year-old can remember getting milk deliveries from Producers Dairy via horse and buggy, swimming in a round pool at the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, and buying a toy truck at Woolworth with a dime.

He also remembers being a first-grader at Our Lady of Good Counsel (now Mary Queen of Peace), where other students referred to the school as “OLGC - Old Ladies Gossip Club.”

But one of Recker’s most legendary stories revolves around his grandfather’s house and its unconventional origins. When his grandfather got married, he found the perfect house for him and his bride…but it was a church located at Pearl and Broadview. Sometime between 1900 and 1910, Recker’s grandfather promptly purchased St. Luke’s Church for $400 and paid $700 to have it moved to West 30th Street and Devonshire, where it was remodeled as a residential home.

“One of the first things he did was remove the steeple,” says Recker, whose middle name is “Louis” after his grandfather. “He also built the front porch with the help of my cousins, who were bricklayers. When his two oldest kids were married, he put two apartment suites in the back and remodeled for a second time so that the whole family could live there.”

“One of the first things he did was remove the steeple,” says Recker, whose middle name is “Louis” after his grandfather. “He also built the front porch with the help of my cousins, who were bricklayers. When his two oldest kids were married, he put two apartment suites in the back and remodeled for a second time so that the whole family could live there.”

Though the house was torn down around 1980, it continues to live on as part of local lore. Recker’s grandfather was also known in the area because he worked for Busch Funeral Home, where he was among the first in Cleveland to receive an embalmer license.

Recker is proud to be the historian of sorts for his family, and it shows in his effervescent retelling of his background. Says Recker, “I never liked history when I was in school, but now I think it’s the best thing ever.”

Good Eats, Great Memories: Michael Loizos

It’s easy for Michael Loizos to remember all the old stores and landmarks that have dotted the Pearl Road streetscape over the decades—after all, his family’s Glenn Restaurant was at the heart of it all. (Read more about Loizos and the Glenn Restaurant’s legacy here.)

Along with the very first Historical Society of Old Brooklyn meeting, “we had a lot of the community meeting there,” says Loizos. “It was a gathering spot for the Boy Scouts, Kiwanis Club, different church groups for Bible study, and American Legion.”

Loizos’ father also felt strongly about supporting local businesses in the area, sourcing from nearby Roy’s, Producers Dairy, and M&W Meat Shop. “We would run out of bread because we were so busy, so I used to make runs over to the bakery at night to get more,” remembers Loizos, who will turn 79 years old this year.

Loizos says his dad also took the meaning of “family restaurant” seriously, extending that meaning to their professional family as well. “He felt he had a responsibility to his employees—it wasn’t just a dollar tradeoff,” says Loizos. “This was their livelihood, and he wanted to make certain to keep it going.”

A Deep-Dive into the Past: Lou Goodwin

Where OH-176 now sits is the stuff of Lou Goodwin’s memories. “Literally, the whole street was our street,” says Goodwin, referring to her extended family’s stretch of farms across Jennings Road during her childhood in the 1950s. “I-76 took my Uncle Bill’s house, my grandpa’s house, and three other houses of our family.”

Though the street no longer exists, the greenhouse farming culture that permeated it and much of Old Brooklyn during that era continues to be a point of fascination. Goodwin can remember her grandfather taking his produce (mostly tomatoes and celery) to Central Market—where Quicken Loans Arena Stands now)—and her and her “dozens of cousins” helping to pick radishes.

Though the street no longer exists, the greenhouse farming culture that permeated it and much of Old Brooklyn during that era continues to be a point of fascination. Goodwin can remember her grandfather taking his produce (mostly tomatoes and celery) to Central Market—where Quicken Loans Arena Stands now)—and her and her “dozens of cousins” helping to pick radishes.

“As a kid, I remember making baskets out of cardboard, and we would each make five cents per basket,” says Goodwin. “Back then, you could get a full basket of tomatoes for a dollar and a quarter.”

One of Goodwin’s fondest memories of the farm is the swimming hole that her grandfather dug using horse-drawn machinery for her and her cousins. (“He dug a drain down in the valley to drain it,” she explains.)

For Goodwin and the rest of her relatives coming of age in Old Brooklyn, the pool was everything. “The pool was just the greatest thing growing up—it was the center of the neighborhood,” says Goodwin. “Four generations enjoyed that pool.”

For Goodwin and the rest of her relatives coming of age in Old Brooklyn, the pool was everything. “The pool was just the greatest thing growing up—it was the center of the neighborhood,” says Goodwin. “Four generations enjoyed that pool.”

When the greenhouse farms began to be displaced by OH-176 construction in the 1960s, efforts were made to save the homes, with Goodwin’s Aunt Betty even petitioning to get her 160-year-old home designated as a historical landmark so it wouldn’t be razed. When it became apparent that their efforts were for naught, Old Brooklyn residents started taking pieces of the home for posterity—from pieces of the slate roof to the fireplace mantle to the front door (now in custody of Ewazen).

“I took a spice bush, irises, and daffodils, and planted them at my own house in Brooklyn, where I’ve now been 27 years,” says Goodwin. “The plants are still alive.”

This article is part of our On the Ground - Old Brooklyn community reporting project in partnership with Old Brooklyn Community Development Corporation, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, Cleveland Development Advisors, and Cleveland Metropolitan School District. Read the rest of our coverage here.