Inmates and CWRU students become colleagues in unique course

While most people form their opinions of the incarcerated by way of The Shawshank Redemption, "Orange is the New Black," or Cool Hand Luke, a group of students from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) is taking a course that will forever reframe such works.

"I think [Orange] is heavily based on stereotypes and that is one of the biggest flaws," says CWRU student Maddie Lyons. "By stereotyping people in prisons, we fail to see them so much as people. Instead they become these caricatures that are further and further removed from humanity and from ourselves."

While Lyons is one of the 16 students taking The Effects of Race, Class and Education: A Dialogue on Current Issues (course number 290M), she has not drawn that opinion solely from within the venerable walls of CWRU.

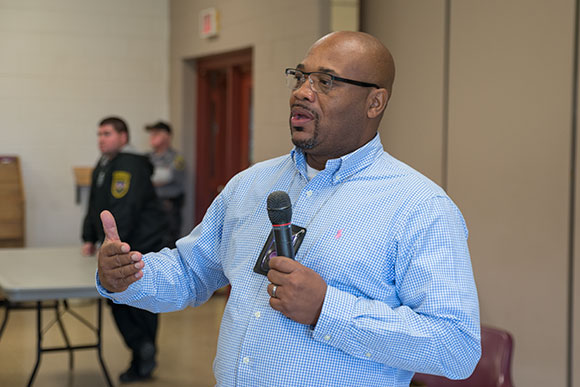

The course is a selection from the university's Seminar Approach to General Education and Scholarship (SAGES) portfolio, which endeavors to advance students' writing abilities and offer balance to an otherwise tech-heavy curriculum. That sounds innocuous enough, but instructor Benjamin Sperry pushes the boundaries of the class both ideologically and physically.

"We're meeting with the SAGES students Monday and Wednesday afternoons," says Sperry while seated on the bench of a crowded luxury limousine bus. "That's this group," he adds of the Case students riding along with him. "I meet with the prisoners Monday and Wednesday mornings."

And the bus is indeed en route to Lorain Correctional Institution (LORCI), a state prison located in Grafton, Ohio, about 35 miles southwest of Cleveland. The visit is the second of two unique face-to-face meetings between the CWRU students (outside students) and group of LORCI inmates (inside students) who have elected to take the course.

Taking it personally

When the group arrives at LORCI, there is copious processing with identification, sign-in sheets and metal detectors. Everyone is cleared and it's off to the chapel, which is a long walk amid institutional buildings that line a vast and neatly groomed lawn free of fallen leaves. Like the processing area, the chapel is immaculate (both are cleaned by inmates) and smells faintly of fresh laundry. The inside students are waiting within.

"Arrange in groups of three chairs," says Sperry, who then opens the session with a series of prompts for the groups to discuss: the perfect meal, a memorable possession and a description of students' families among others.

So it begins.

An inside student describes the first car he had, which didn’t run. "We would just sit in there: me and my little friends. I was really young, I couldn't drive."

"I remember my first car I bought," recalls another inside student. "I paid $100 for it. Somebody had it sitting in their yard."

The first inside student recalls a car a family member bought him. "It's still sitting in the garage because I never went and got a license."

"I have a car like that," adds the other inside student, who hasn't had a license for decades.

Animated by the memories, the inside students rattle off makes, models and year numbers. The trio falls silent and a few awkward beats pass.

"I drive a Camry," says the outside student, and the three erupt with laughter.

Another group discusses family.

"My mom's like really really goofy and my brother is too," says one giggling outside student. "It's just a lot of silliness. We're always laughing, which is awesome but sometimes it's just like, weird."

"Sounds like my sister," notes an inside student.

"My family sent me to the best schools and everything," offers another inside student. "I did the dumbest stuff."

Books are yet another topic.

"One time I read a biography of Al Capone and some of the things they went through," says one inside student, " … to know that one of the biggest influential crime figures of all time got syphilis, that just kind of threw me off."

"He died from that," adds another inside student.

Sperry notes the importance of starting these sessions with casual conversations.

"All of a sudden you've got all this common ground," he says. "All the stereotypes we have about prisoners - about everybody - those things melt away when you actually get to know the people. It's a wonderful experience for an educator to see that kind of energy."

Inside/Outside: two groups, one class

Sperry, who has been involved with education in prisons and jails for more than 15 years, pitched the course to CWRU two years ago. 290M is based on the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program, which originated at Temple University. While Sperry is trained in that program, he has adapted it into his own version.

The average age of the outside students is about 19. The inside students range from looking utterly boyish to grandfatherly. The Lorain institution is largely a reception facility, processing inmates such as Ariel Castro immediately after sentencing. Here they are evaluated and then placed in one of the state's permanent prisons. Hence, the average stay in LORCI is 30 days. The inside students, however, are part of a different "cadre" population within the prison, which includes about 250 men serving out their entire sentences here.

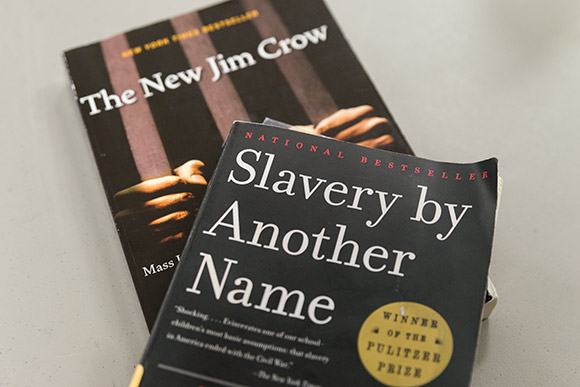

The 290M curriculum includes reading a number of books such as The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, the two in-person visits, a number of teleconferences including both groups of students and writing papers.

The 290M curriculum includes reading a number of books such as the ones shown here

The 290M curriculum includes reading a number of books such as the ones shown here

"They're building a little bit of this sense of scholarly conversation that's going on alongside the popular conversation on these issues of racial and social justice and so forth," says Steve Pinkerton, Sperry's writing co-instructor for the course. "They're getting smarter and smarter in the ways they're articulating their positions on these things, so that's great. I've been glad to see an increasing sophistication in the way they're talking about these subjects."

Carl Mansfield, LORCI correction specialist, sets criteria for the inside students. They must have a high school diploma or GED. They must be able to read and write on a certain level and have some math skills. This is the second such course at the prison. Mansfield has had a healthy response for both, with about two-dozen applicants for the 15 slots.

"It gives them feedback on what's going on on the outside," says Mansfield. "There's a lot of good communication between them. For both inside and outside students, it's such a different culture for them and it's amazing how the group came together."

Mansfield notes the class is pretty much like any college class, with all the students following the same 16-week curriculum. "Our inside students in the teleconferences, they held their own," he says. They're very intelligent."

One glaring difference remains between the two groups. The CWRU students are obviously earning college credit. The LORCI students do not, which Sperry is trying to change.

"I've been agitating for that," says Sperry. "For them to be able to step out of prison with their freshman year of college under their belt, or half a year of college - something like that would be great."

Until then, while the inside students get certificates documenting their efforts, the program serves mostly as a diversion for them.

"This is basically a program just to keep them going," says Mansfield.

"I grew up in it"

The main body of the visit constitutes a series of 10-minute conversations amid four breakout groups. Prompt questions, mainly about racism, oppression and incarceration, kindle evocative discussions.

A sampling of comments:

"I have no fears of discrimination and racism because I grew up in it," says one inside student. "There was a lot of racism going on in the family. They called me the n-word so many times, I thought it was my name."

"I'm a white male, so that has its privilege in this country," says an outside student. "I guess it is difficult having a dialogue about racism because I haven't really experienced that kind of difficulty in my life." He continues, "You're uncomfortable with bringing up the issue. You feel like you're part of the system that perpetrates that."

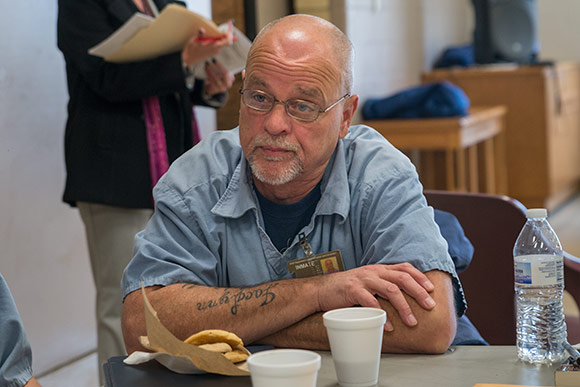

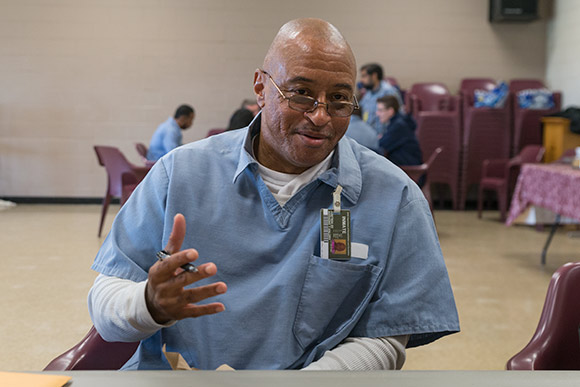

A CWRU students listens while an inmate discussus his life durring a breakout group

A CWRU students listens while an inmate discussus his life durring a breakout group

An inside students comments during a discussion on violence: "People don't understand that that type of behavior is a learned behavior," he says. "It's passed down from generation to generation to generation to generation." He continues: "It's synonymous with guys with recidivism coming back and forth to prison. Somebody has to break that cycle. Somebody has to be bold enough to stand up against that. You have to be bold enough to say: well I'm not going to participate in the things that got me in here and the things that others do."

An outside student recalls a security screening during a family trip. "We all passed through except my dad, whose name is Mohamed. He was in the airport for like, three hours."

She continues with a recollection from September 11, 2001: "From my school window, I could see the towers falling," she says. "We actually had a controversy where they thought they were teaching us how to build bombs. So they shut down the school for like, two days. We were kindergarteners. I was learning how to tell time."

Another inside student recalls a threat from a family member when he was about the same age. "He told me if I ever brought a black girl home he'd shoot me."

"I look white," notes an outside student, "but I’m actually Puerto Rican."

Other topics include discrimination against felons and inmates with mental health issues. One inside student recalls his tangle with the Aryan Brotherhood while serving time. Several of them concede they put themselves inside the walls of LORCI.

And while the inside students tend to dominate the discussions, it is clear that every interaction is fueled by mutual respect.

Reaching across barriers

On the ride back to campus, while the limo's champagne buckets contain no ice or bubbly, the outside students are animated and the din rises on high with laughter and excited chatter. They are fueled by the experience as well as the refreshments served by non-student inmates during the meeting.

When asked if the meeting was emotionally taxing, outside student Maddie Lyons laughs and says it was not. "(An inside student) took like eight cookies and I took like four and we sat next to each other and we took pictures."

When asked, however, what she would tell people who might criticize the program as too sympathetic to the inside students, Kyons responds very seriously.

"I would probably say what Ben said to us. He asked us how we would feel if we were judged for the worst thing we ever did. I think that was thought provoking for most, if not all, of us because that is what differentiates us from the inside students. They are in prison because they are being judged for what is probably the worst thing they ever did.

"We have all of the things that we regret - everybody has," continues Lyons, noting that inside students carry those regrets within the walls of LORCI and outside students carry them wherever they choose.

"The truth is they're people," she says, highlighting the subtle goal of 290M.

"As a university, as a society, we have a mission to reach across barriers," adds Sperry, "and that's what I'm trying to do."