the cutting edge: three cleveland medical innovations bound for great things

Modern medicine is constantly innovating ways to improve the length and quality of human life. An aging population has made the need for new medicines and medical technology even greater, even as suit-and-tie types in Washington squabble over the reformation of health care.

In Cleveland, researchers at the Cleveland Clinic are working with medical manufacturers on treatments and technologies that can blast a brain tumor with a laser, detect a concussion using an iPad, and test for prostate cancer by way of genetics. These innovations are at various stages of progress, but the minds directly involved with their use are certain that these Cleveland-centric innovations are destined for great things.

Testing for a better way

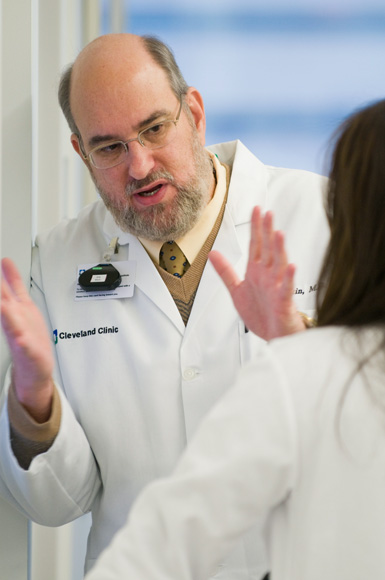

When a man is diagnosed with prostate cancer, the first question he likely will ask is, "How soon can I be treated?" That query can be misleading as treatment is not always the answer, particularly for low-risk cases, explains Dr. Eric Klein, chairman of the Clinic's Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute.

About 90 percent of low-risk patients immediately undergo radiation therapy or have their prostates removed even though the chances of their cancer becoming deadly is less than three percent, says Klein. These radical treatments come with life-altering side effects, including impotence and incontinence.

Klein believes he's found a better way for patients to answer that crucial question about their disease. The Oncotype DX Prostate Test is a new genetic-based assessment that can help doctors more accurately determine how aggressive a cancer is, and whether surgery or radiation therapy truly is necessary, he says.

The test measures gene expression in prostate cancer tissue samples from small needle biopsy specimens. Genetic information is translated into a Genomic Prostate Score (GPS) that ranges from 0 to 100. The score is combined with other factors to determine the level of prostate cancer risk before any serious treatment is begun.

Using genetics, even a tiny tissue sample can tell a larger tale. "A regular biopsy may find one low-grade tumor," says Klein. "This [test] can measure the biology of the entire prostate."

Active surveillance through periodic visits and annual biopsies is a better option for lower-risk cancers than radiation or prostate removal, Klein says. The Oncotype DX test is not yet the new norm, but studies conducted with manufacturer Genomic Health on 700 patients at Cleveland Clinic identified genes important in both low- and high-grade tumors.

The often slow growth of prostate cancer means the effectiveness of surveillance will not be known for years, says Klein. Still, the genetic test that has gained traction in Cleveland at least gives men that all-important power of choice.

"If the cancer isn't killing you, there's no reason to go through the side effects of treatment," says Klein. "This test has no side effects."

Blasting brain tumors with heat

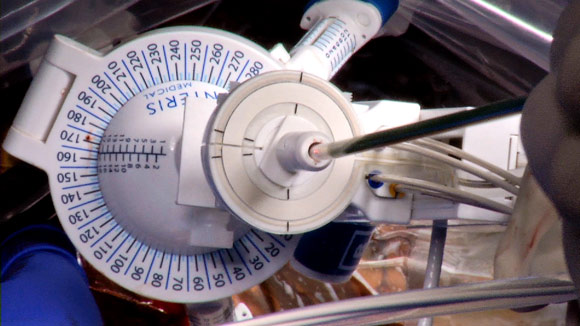

Recent years have seen Cleveland Clinic neurosurgeons pursue cutting-edge brain tumor surgery technology. An innovation called NeuroBlate takes "cutting" out of the equation, instead using a concentrated laser that destroys cancerous cells while sparing healthy tissue.

"It literally cooks the tumor from inside out," says Dr. Gene Barnett, director of the hospital system's brain tumor and neuro-oncology center.

The Clinic's Rose Ella Burkhardt Brain Tumor and Neuro-Oncology Center was first in the world to test the NeuroBlate in humans. The process -- in medical parlance called laser interstitial thermal therapy (LITT) -- involves a slender, high-intensity laser probe inserted through a small hole in the patient's skull. The tip of the probe emits 30-second pulses of laser energy, heating and coagulating the tumor while protecting normal tissue in neighboring areas. A surgeon controls and monitors the four- to five-hour procedure via computer screen, steering the 160-degree heat to eliminate the diseased cells.

NeuroBlate is best suited for malignant tumors situated deep in the brain or deemed too risky for surgery, says Barnett. Unlike conventional surgery, the therapy is minimally invasive, and allows patients to leave the hospital in just one or two days following the treatment.

Barnett has performed about 80 procedures since the Canadian-developed technology came online in 2009. It's too early to determine how effective NeuroBlate is in terms of survival rate, but the technology has effectively put cancer into remission at higher rates than more common treatments, he notes. As for side effects, the most common risk with NeuroBlate is temporary swelling around the treated area, which is usually managed with medication.

The precision laser could have future applications in blasting tumors from other organs in addition to the brain, or treating patients with radiation injuries. For now, Barnett is pleased to have a superior technology right here in Cleveland that takes some of the time and risk out of a complicated surgery.

A knock-out idea

The National Football League recently settled a concussion lawsuit for $765 million, highlighting the dangers even world class athletes face after absorbing a vicious hit. Take that to the high school level, and it’s doubly difficult for coaches, trainers and even doctors to determine when athletes have a concussion, not to mention when it’s appropriate for them to get back on the field.

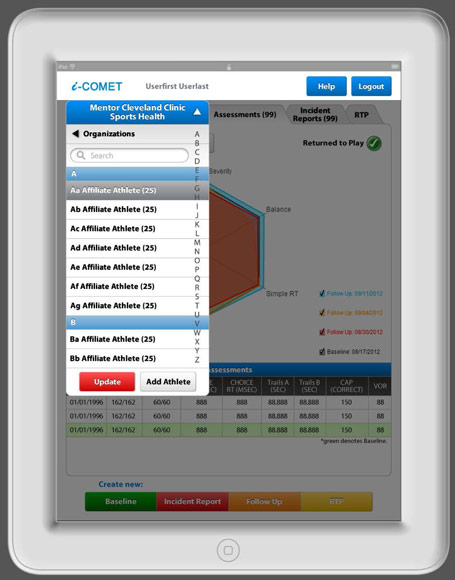

An iPad app developed at the Clinic is helping to answer those questions more completely by compiling an abundance of information in an easy-to-understand format. The Cleveland Clinic Concussion Assessment System (C3), created by biomechanical engineer Dr. Jay Alberts, measures concussion parameters including balance, posture and visual acuity.

"It provides objective data for all the major signs of concussion," says Alberts.

Testing balance is especially critical when monitoring for a concussion, maintains the app designer. Using the iPad's self-contained gyroscope and accelerometer, the app can measure and chart balance, capturing subtle movements that wouldn’t be picked up by an observer. With the tablet strapped to the athlete's back, a sideline clinician can view a detailed graphic that shows whether or not a player's vision and balance has sufficiently improved.

The app's best use will be to augment standard concussion testing, notes Alberts, who sustained a concussion himself as a defensive back in high school. "It just takes some of the subjectivity out of it," he says.

C3 is being tested by 56 local high schools as well as at a handful of universities in the eastern U.S. The app also is in use at a rural high school in Alberts' home state of Iowa. Alberts wants to prove that this system can be implemented anywhere, no matter how underserved, and he's thrilled that Cleveland is at the heart of the research.

"This isn't a 'Concussion 5000' app that will definitely tell you if you have a concussion," says Alberts. "But it can be used as a tool to get objective, quantitative information."