missed opportunity? what must happen for new roadway to live up to its name

Lisbon Avenue in Cleveland’s Forgotten Triangle -- the area bounded by Kinsman, Woodland and Woodhill on the east side -- takes “ruin porn” to a lurid new extreme.

The street resembles a dumping ground more than it does a community. It’s dotted with boarded-up homes and vacant, overgrown lots strewn with trash, old tires, TV parts and even a burned-out car. One house, sporting a roof with a hole punched clear through it, is likely to fall down if the city doesn’t get to it first.

Yet this still is a community, however forgotten it might be. It includes residents on half-empty streets, aging industrial businesses in squat brick buildings, and makeshift churches that might themselves need saving. For the most part, it's cut off from the growing sense of prosperity that one might find in University Circle or downtown.

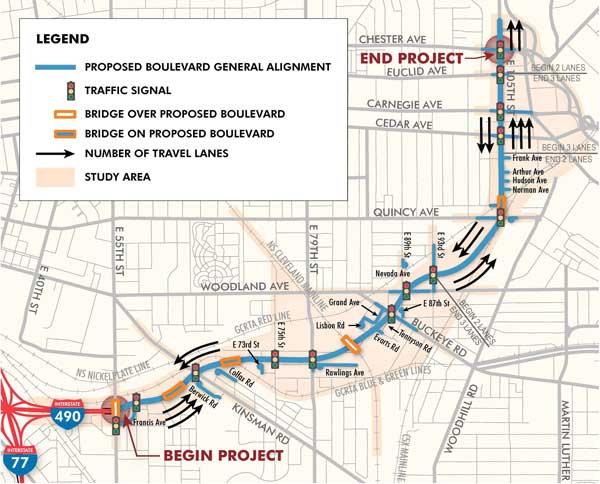

Such disheartening disinvestment exists along much of Cleveland’s so-called Opportunity Corridor, a 3.5 mile planned roadway that would connect I-490 with University Circle. The Corridor, which was conceived 30 years ago and has been in the works for over a decade, will extend the I-490 stub that dead-ends at E. 55th Street, shortening commutes to and from University Circle and boosting development along the way.

The 35 mph road, which requires the demolition of 90 homes and businesses, is being promoted as a bike- and pedestrian-friendly boulevard rather than just a way to zoom through the area. It features 13 intersections, a landscaped median, a bike trail, and new lighting, benches, bike racks and trash receptacles. Five lanes traverse most of the Corridor, but it narrows to four lanes near University Circle.

The Opportunity Corridor, estimated to cost $331 million, was recently awarded funding from the Ohio Department of Transportation. Phase I, running from E. 105th Street to Quincy Avenue, is scheduled to start in the fall of 2014 and be completed by 2016, while Phase II, stretching from Quincy to E. 55th, should start in 2015 and wrap up by 2019.

“We’re designing a road that could allow future development -- commercial, residential and mixed-use,” says Deb Janik, Senior Vice President of Real Estate Development with the Greater Cleveland Partnership (GCP), the business group guiding the effort. “We designed it so that it is well-connected, able to manage the speed that’s been conveyed to the public, and in a way that spurs neighborhood development.”

The question is whether the Opportunity Corridor can avoid the sins of the past -- when highways ripped apart Cleveland neighborhoods -- while delivering on promised economic development.

There still is a great deal of work to do and plenty of unanswered questions, even as the project barrels forward like an 18-wheeler on a highway.

Seizing the Opportunity?

Some aren’t so sure that the Opportunity Corridor will live up to its namesake. Critics cite displacement of local businesses and families, the gargantuan cost, lack of investment in existing roads, unclear benefits to the local communities and the lack of comprehensive planning -- including plans for transit-oriented development -- as reasons for skepticism.

“This could be a revolutionary investment in bike-, transit- and pedestrian-friendly infrastructure that would move the city forward huge steps, but instead we’re going to get a three-mile road,” says Angie Schmitt, a member of the Coalition for Transportation Equity and a vocal opponent of the road. “There have been a lot of negative comments during the public forums, but they’re going to modify a few things and march forward.”

The goal of the Opportunity Corridor, as its name suggests, is not simply to give Westsiders an "opportunity" to breeze through impoverished neighborhoods on their way to the orchestra, but to open up economic opportunities in those very communities.

A 2011 study by Allegro Realty for the Greater Cleveland Partnership says the Corridor could generate 2,300 permanent jobs and 3,330 temporary jobs with a payroll of $1.1 billion. This is in a part of town where average household income is under $20,000.

Yet Schmitt says the project could realize far greater economic and community benefits if the money was spent improving existing roadways or enhancing public transportation. She has not given up efforts to stop the project, yet she is also trying to influence the roadway’s design, pressing ODOT to make it more of a multi-modal road.

It appears Schmitt and other advocates are making some headway. Following several feisty public meetings in which project planners got an earful, ODOT is now considering reducing lane widths from 12 to 11 feet and reducing the number of lanes from three to two in sections. This would slightly reduce the distances between intersections, thus making it easier to cross, says Amanda McFarland, a spokesperson with ODOT.

The Environmental Protection Agency also recently provided comments on the draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Opportunity Corridor. In its letter, the EPA stated the need for a community benefits agreement, a plan for transit-oriented development and better storm water infrastructure, among other issues.

Yet questions raised by residents and advocates during recent community meetings are causing some to ask: Will community input be listened to and incorporated into final designs given that the Opportunity Corridor is being placed on the fast track to completion?

More Changes Needed

Although ODOT’s changes might be a step in the right direction, advocates say they fall well short of what’s needed for Cleveland to capitalize on this opportunity. Terry Schwarz, Director of Kent State’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative, argues that additional intersections, green infrastructure and transit connections all are critically important.

“This is located very close to the Red Line, and it’s one of those places in the city where we could get lots and lots of riders if the Opportunity Corridor lives up to its promise,” says Schwarz. “ODOT has talked about transit, but it doesn’t look at all like the connections on the roadway are made with mass transit riders in mind.”

For example, Schwarz believes that E. 79th Street needs a good streetscape design, the rapid station needs to be redesigned to be ADA-accessible, and a plan for transit-oriented development is needed. Unfortunately, the station might be forced to close if it’s not redeveloped to be ADA-accessible in a few years, according to a member of the Citizens Advisory Committee, who spoke off the record about the rapid station.

RTA spokesperson Mary Shaffer declined to comment on redevelopment of the E. 79th Street station, other than saying that it's not currently scheduled to close. Currently, the station suffers from low ridership numbers, but Schwarz says they could turn around with investment.

Others have raised concerns that the Opportunity Corridor is being oversold to the community and that the touted community and economic benefits just won’t materialize.

“If the roadway was done right, it could bring opportunity,” says Tim Tramble, Director of Burton Bell Carr Development, the nonprofit CDC in Central. “If it’s just an infrastructure project -- and by all indications that’s what it appears to be -- then it’s not going to do any good for the community, and we won’t leverage the highest and best use for Cleveland.”

Tramble would like to see the city, Greater Cleveland Partnership and other partners involved in the project fund a comprehensive land acquisition strategy. Although 400-plus acres of land could be available for development along the Corridor, there is no land acquisition taking place right now beyond the city’s land bank process, he says.

Instead, he’s seeing real estate speculators becoming active in the community, buying properties and then sitting on them or turning around and trying to flip them for a profit.

“A lot more work could be done to assemble those parcels,” says Tramble, citing the success of BBC’s assemblage of land for the Green City Growers greenhouse. “We could be doing more to ensure that it’s an economic generator for the community.”

City of Cleveland Planning Director Bob Brown defends the city’s efforts, stating that it’s now ready to begin land assembly efforts in collaboration with BBC and other groups. “The city has not started any active land assembly, but we are certainly poised to do that now that the project has finally become real in terms of its funding,” he says.

Slavic Village Sees Hope

If residents and community leaders in the Forgotten Triangle area are skeptical of the project’s benefits, members of the Slavic Village community are more hopeful. Long separated from commercial districts south of them by the unwelcoming intersection where I-490 bangs into E. 55th Street, they believe that the Opportunity Corridor could foster more pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use development within their neighborhood.

“We see this as an opportunity to right the design debacle of 490,” says Marie Kittredge, Executive Director of Slavic Village CDC. “ODOT could have said, ‘Oh, we’ll go under 55th Street and bypass your neighborhood completely,’ but instead they’re adding an access road and building a pedestrian bridge to reach the 55th Street rapid station.”

The Opportunity Corridor will in fact be built as an underpass here, yet this will make 55th more pedestrian- and bike-friendly, thus attracting development, Kittredge says. Slavic Village CDC has developed a plan for mixed-income housing and is trying to attract a developer. With plenty of land, the area could be ripe for a big makeover.

Resident Joyce Hairson, who lives in the Hyacinth neighborhood, owns a house directly in the path of the Opportunity Corridor. Her home will be bought by ODOT and demolished to make room for the roadway. However, she plans to buy another home in the Slavic Village neighborhood, which she says finally is on the upswing after hard times.

“This was a cute area, with kids playing, manicured lawns and the whole bit,” says Hairston, who has lived on Butler Avenue since 1995. “But the foreclosure crisis hit us really hard. The street I’m on had 17 houses, but by the time the scavengers got finished going through them, there were seven left. The rest got torn down.”

“I’m proud of my neighborhood,” adds Hairston, who supports the Corridor because she believes it will bring more people and economic development activity to the community. “I’m staying and it’s getting better every day. More people should come here to see it.”

Photos Bob Perkoski

Interested in learning more? Community meetings on the Opportunity Corridor will be held Dec. 14th-15th. More info here.