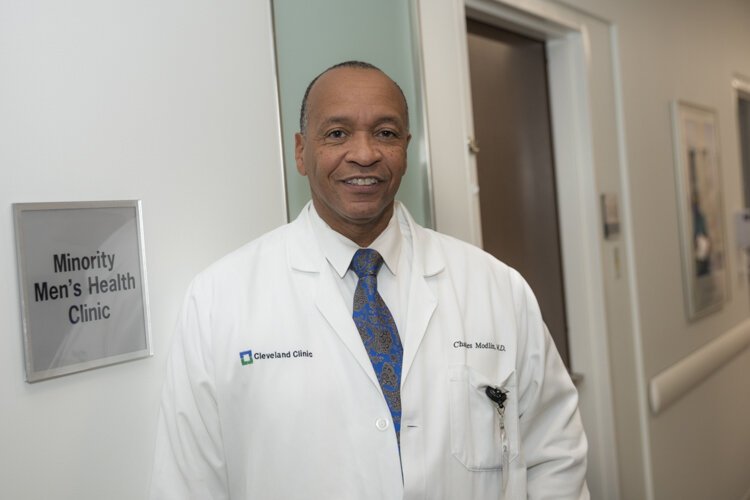

Cleveland Clinic doctor leads effort to reduce health disparities among black men

The health of black men worries Dr. Charles Modlin. The numbers are clear. They’re many times more likely to contract various serious illnesses than other Americans. So the Cleveland Clinic urologist is doing something about it.

In 2003, he launched the Minority Men’s Health Fair in Cleveland. Now he is bringing the Clinic’s 20-plus institutes together under an umbrella organization to address the glaring health disparities in a comprehensive way.

Dr. Charles Modlin launched the Minority Men’s Health Fair in Cleveland in 2003 to help eliminate health disparities among black men.“There’s a lot of helplessness and hopelessness that minority men feel,” Modlin says. “They may think that whatever happens to them, society doesn’t really care. Through this health fair and other activities, I think we’ve shown that we do care, they do matter to their families, their community and society.”

Dr. Charles Modlin launched the Minority Men’s Health Fair in Cleveland in 2003 to help eliminate health disparities among black men.“There’s a lot of helplessness and hopelessness that minority men feel,” Modlin says. “They may think that whatever happens to them, society doesn’t really care. Through this health fair and other activities, I think we’ve shown that we do care, they do matter to their families, their community and society.”

The annual health fair was a good start, he says. “The first disease we wanted to target was prostate cancer, which was twice as common in African-American men as white men and where the death rate was twice as high,” Modlin says. “A lot of it is delayed presentation. We know that if we can diagnose prostate cancer in the early stages, then we can cure black men at the same rate as white men.”

Now Modlin, an African-American kidney transplant surgeon who has completed more than 500 transplants at the Clinic in the past 20 years, is stitching together the Clinic’s new Multicultural Health Center of Excellence. It will help the Clinic’s diverse institutes develop their own programs and approaches to address the health disparities, building on the success of the health fair, as well as the Minority Men’s Health Center, which Modlin also helped launch in 2003.

“What we’re doing basically is getting ready to take this to the next level, amplify it and spread it across the entire Cleveland Clinic,” he says.

Dr. Charles Modlin talks with a patient at the Minority Men’s Health Center at the Cleveland Clinic.Many doctors are unaware of health disparities and how to address them, says Modlin, who is the only black transplant surgeon in the Clinic’s history. “A lot of times, poor communication may lead to poor patient compliance and follow-up,” he says. “A patient may think a caregiver doesn’t care about them or is not listening to them. At the same time, patients also need to be more health literate.”

Dr. Charles Modlin talks with a patient at the Minority Men’s Health Center at the Cleveland Clinic.Many doctors are unaware of health disparities and how to address them, says Modlin, who is the only black transplant surgeon in the Clinic’s history. “A lot of times, poor communication may lead to poor patient compliance and follow-up,” he says. “A patient may think a caregiver doesn’t care about them or is not listening to them. At the same time, patients also need to be more health literate.”

Several new programs already have been launched under the Multicultural Health Center of Excellence. One is the Clinic’s Minority Stroke Program, which is housed under the Cerebrovascular Center in the Neurological Institute. Its goal is to “increase stroke awareness among minority groups in order to lower stroke rates and improve stroke outcomes,” according to its website.

Another example is the Clinic’s Center for Multicultural Cardiovascular Care, which is housed under the Arnold Miller Family Heart and Vascular Institute. It aims to “research and understand the nature of heart and vascular diseases that are unique to special groups, identify appropriate testing for high risk populations, provide access to treatment, and understand how treatments differ among races and cultures.”

The list of other new Clinic programs under the umbrella is long. They include the Neurological Institute's Minority Stroke Center; the Glickman Urological & Kidney Institute Minority Kidney & Hypertension Center; the Orthopedic & Rheumatologic Institute Minority Center; and the Respiratory Institute Minority Lung Health Center.

The Clinic’s marketing department is working internally on creating standardized individual webpages for each of these "center" programs before going live externally.

The launch of this new initiative shows that the Clinic is committed to reducing health disparities, Modlin says. “The directive is for us to try to take care of patients even when they’re not in front of us in an exam room. One example is that it’s now built into physicians’ schedule every week that they have time to stop and manage patients. There may be patients that we know are not coming back, patients who missed lab draws or didn’t get that X-ray we ordered, and we proactively call them and remind them that they missed their appointment and ask, ‘What’s going on, what can we do to help you?’”

The launch of this new initiative shows that the Clinic is committed to reducing health disparities, Modlin says. “The directive is for us to try to take care of patients even when they’re not in front of us in an exam room. One example is that it’s now built into physicians’ schedule every week that they have time to stop and manage patients. There may be patients that we know are not coming back, patients who missed lab draws or didn’t get that X-ray we ordered, and we proactively call them and remind them that they missed their appointment and ask, ‘What’s going on, what can we do to help you?’”

Another mission of the Center for Multicultural Health Excellence will be to champion diversity in the field. Having more minority doctors is important because it can improve minority patient outcomes, says Modlin, who is one of only an exceedingly small number of African-American transplant doctors in the U.S.

The new center will also conduct more research into the causes behind minority health disparities, with the aim of identifying genetic variants that cause varying responses in disease and health. For example, the newly launched African-American Male Biobank houses a growing collection of blood and urine samples, accompanied by a database of donor demographics, including age, medical history and family history. The biobank, which is one of the only African-American biobanks in the nation, is approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Efforts to reduce health disparities across the U.S. are beginning to see results, but much more work is needed, Modlin says. “Since physicians have been taking a proactive approach to screening for prostate cancer, we have actually seen a lessening of some of the gaps,” he says, citing one example.

Yet he has seen firsthand how efforts to reduce health disparities can make a difference. “I can’t tell you how many times people say, ‘I never would have come in without this doctor,’ or how many times we’ve saved people’s lives at the health fair,” he says.

The Clinic’s Minority Men’s Health Fair, which takes place annually in April, has expanded to four Northeast Ohio locations and has reached more than 35,000 people with free early prevention screenings.

Three Calls to Action:

- Encourage the family and friends in your life to stay on top of their health, establish a relationship with a primary care doctor, and go to their annual check-ups.

- Know your family health history. Ask your parents or relatives about any past health issues that might be hereditary.

- Encourage the men in your life to attend the 18th annual Minority Men’s Health Fair at Cleveland Clinic on April 23, 2020.

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.