the 25th street shuffle: will success kill ohio city?

Ohio City is changing fast, and nowhere is that more apparent than along W. 25th Street. Now, you have sidewalk seating, fine food, and a craft beer cluster that rivals any in the country.

Back in the '80s, though, the neighborhood was more a place of necessity. For instance, people got eye exams there, they bought auto parts, they did their banking. But before long, there started to be less there there. Cleveland’s population decline in the '90s took many small businesses with it -- and W. 25th Street was dying. So was its necessity.

“Man, I remember how empty it was,” says Mike Kaplan, co-owner of the Glass Bubble Project, which he opened in 1999. “There was nothing. People were always getting robbed right here,” he added, pointing to a spot not far from his Ohio City glass-blowing studio.

Kaplan was right. The area struggled with disinvestment and its effects. Beyond crime, there was the desperation to fill empty storefronts regardless of fit or purpose. Take the infamous -- and now defunct -- Club Moda. Its crime-laden presence made it harder for existing businesses to hang on, or to entice new businesses to move in.

“On Sunday nights, we would traditionally duck behind the bar dodging bullets [from Moda]," recalls Old Angle Tavern owner Alex Gleason. "It was crazy!”

Things are different now, because thanks to a spate of new restaurants, breweries, and shops -- combined with other outfits that range from a Lebanese deli, to a barber college, to one of the largest urban farms in the country -- the area fills new needs, not the least of which is providing a place where residents of all stripes can once again experience community.

Asked about the changes over the last 10-plus years, Kaplan, who first joined the area during its "hardcore art co-op scene,” spoke matter-of-factly, neither resenting nor revering his neighborhood's evolution: “It’s overwhelmingly busy. It’s overwhelming, the change. I hate to say I don’t like it. I like it -- it happened.”

What exactly has happened here?

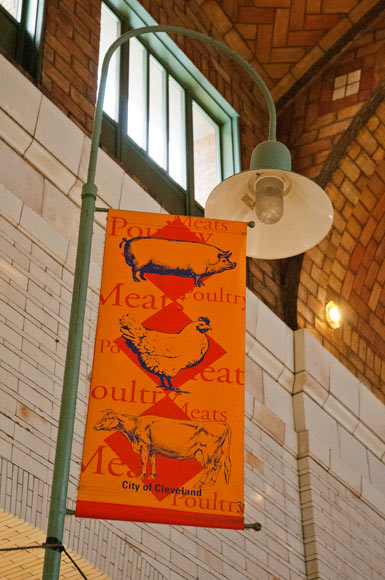

Well, the short answer is that the area grew from its one longstanding asset: the West Side Market, which is a distinguishing jewel in the stubbornly resilient, if tarnished, crown of Cleveland. When you carve down to the identity of the market, you find culture, food and a historical place of commerce.

Project for Public Spaces calls these areas Market Cities, where public markets “act as hubs for the region and function as great multi-use destinations, with many activities clustering nearby."

In all, it’s a positive time in the evolution of the street, as it is a success that still smells of Cleveland -- in its sights and sounds, at the bus stop, the bank, or the bar.

Of course, the big concern is whether or not success will sanitize the strip, taking the authenticity and diversity with it.

Urban areas that have been revitalized often do so at the expense of their distinctiveness. This is rapidly occurring in places like New York City and Portland. Jane Jacobs, the great city thinker, calls this the “self-destruction of diversity.” Put simply, an area becomes intriguing, spaces fill up, and higher rents begin “crowding out and overwhelming less profitable forms of use.”

Eventually, many of the local places -- the Lebanese delis and glass-blowing studios of the world -- can’t compete with the deep-pocketed chains. Before long, the real feel of the neighborhood gives way to a soulless corporate aesthetic that neutralizes why the area was attractive in the first place.

This issue is not lost on local business owners: They don’t want chains; they don’t want “cheese.” The only question is if it can be stopped. And if so, how?

Gleason, for one, thinks it comes down to the fact that the current local business community is one of owners who get along via a collective goal. He believes that teamwork and a shared vision -- along with help from city council and the likes of Ohio City Inc. -- can effectively guide long-term planning.

“I am all for the multiplier effect as long as it is a good multiplier," Gleason says. "All the owners feel that way. We want W. 25th Street to be kept as authentic to Cleveland as possible. We have to. That integrity is the reason we exist. It’s why people are coming.”

Gleason feels that much of the neighborhood's authenticity is driven by the character and working-class backgrounds of the people who operate businesses here. “Most of the owners are from the restaurant business," he points out. "We spent our life getting our hands dirty. I grew up here. Others have pasts here and histories of busting our ass in the business. That’s Cleveland, and so there is a lot of Cleveland pride.”

Sam McNulty, one of the biggest players in the area’s revitalization, is used to the uncertainty surrounding W. 25th Street. After opening the Bier Markt in 2005, McNulty added other establishments to the street, including Bar Cento and Market Garden Brewery, which utilized what once was a live poultry shop. The doubts back then had less to do with how to maintain success than whether or not success was even possible.

“I kept hearing that I was just going to be cannibalizing my businesses,” McNulty said, referring to the notion that the area had limited appeal, which could keep only a few establishments busy. But that didn’t happen. Instead, sales grew exponentially at all of his businesses once the cluster began revving.

So McNulty doubled down, recently opening a small-batch brewery called Nano Brew Cleveland that will act as a taste-tester for the bigger brewery down the block. McNulty says the chorus of whether or not success can happen on W. 25th has quieted. “When we announced [our latest projects], people finally stopped commenting on the cannibalization theory and realized that growing an authentic district increased business for all.”

Of course, questions remain. Specifically, can the street be kept authentic and diverse, or will gentrification and homogenization “eat the Cleveland” out of one of the city’s historically rich spines?

“Look, at the end of the day we live in a free market society, so of course there is a chance that any kind of business can come in,” explains McNulty.

To counter that, an unprecedented level of cooperation between business owners, developers and Ohio City Inc., notes McNulty, acts as a neighborhood steering committee of sorts. When a space does open up, locals often act as feeders to developers. This is precisely how the Ohio City Hostel came to be, with McNulty acting as conduit between hostel owner Mark Raymond and developer Ari Maron.

This organic “If you need space, I can get you space” redevelopment strategy is the antithesis to global city development, by which investors don’t have their ears to the rails -- not that they would heed the chatter if they did.

Can this vision and approach hold? Time will tell, of course. But the fact that we are even asking the question "Can success kill a part of Cleveland?" means both that good things are happening and efforts are being made to manage and maintain them.

After all, Cleveland has survived this long without exorbitantly selling its soul. Granted, there haven’t exactly been a lot of buyers, but that's changing.

Who knows? Maybe there is something in the Lake Erie water that makes how we do neighborhood revitalization different. If that’s the case, this Cleveland microbrew thing could really be a “win-win.” We just can’t get drunk with our desire to be wanted.

Photos Bob Perkoski