Should Cleveland declare racism a public health crisis?

Racism. A word evoking a wide range of both defensive and offensive emotions. It deeply divides our country, our states and even our city. Cleveland. A place where slaves fleeing bondage came for a taste of freedom. They called it “Station Hope.”

Yet, when slavery ended, racism prevailed. What is its impact today?

This year marks 400 years since the first Africans arrived on these shores involuntarily. Ronnie Dunn, interim chief diversity officer and associate professor of urban affairs at Cleveland State University, convened a committee to observe this momentous anniversary.

Ronnie Dunn, interim chief diversity officer and associate professor of urban affairs at Cleveland State University“The reason I called the planning committee together, I knew it was coming up, and nothing was being done. Something of this magnitude couldn’t go unobserved,” he says.

Ronnie Dunn, interim chief diversity officer and associate professor of urban affairs at Cleveland State University“The reason I called the planning committee together, I knew it was coming up, and nothing was being done. Something of this magnitude couldn’t go unobserved,” he says.

Most importantly, the committee wanted it to be a collaborative effort.

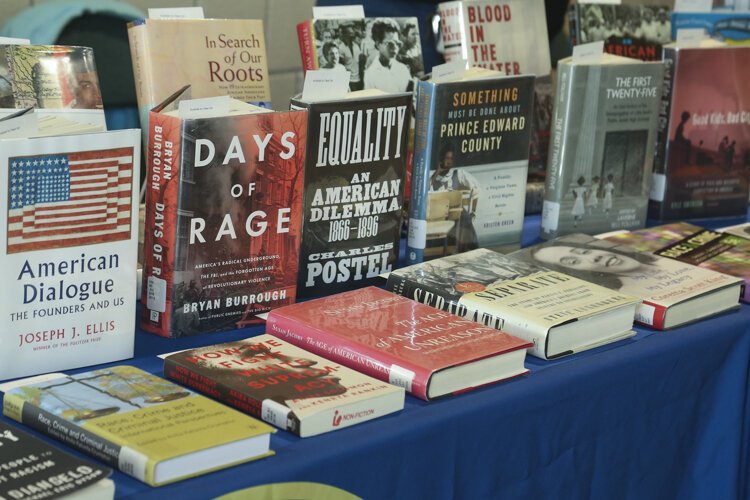

Dubbed Project 400, the commemoration kicked off in August with a series of events, including a conference at CSU. A Call to Action summit titled 400 Years of Inequity is slated for Friday and Saturday, Nov. 8 and 9, at Public Auditorium. Project 400 continues with the Kuumba Arts Festival on Saturday, Dec. 7, at Berkman Hall Auditorium on the CSU campus. Other events are being added to the calendar, Dunn said.

The notion of racism as a public health crisis will be examined at the 400 Years of Inequity summit, convened by the YWCA of Greater Cleveland and First Year Cleveland, an infant mortality reduction program. Guest speakers include renowned authors and lecturers Isabel Wilkerson, John A. Powell, Harriet Washington, Darrick Hamilton, and Dr. Gail Christopher.

“Structural racism is not going to be eradicated in our lifetime, but this is the appropriate time to make a concerted effort to have the important conversations,” Dunn says.

This notion isn’t new, he says. Milwaukee first declared it, and a study by the city of Seattle found racism embedded in every level of government. This summit is part of that legacy of work, Dunn says.

“The residual effects of slavery are apparent,” he says. Dunn hopes to enlighten and change the narrative in the dominant community and shift the focus to eradicating the existing structural racism. “Only in the last 55 years have we experienced full citizenship. This country has not had a sustained effort to eradicate racism. We’re experiencing a second reconstruction, and you see the backlash.”

Margaret Mitchell, executive director of YWCA Greater ClevelandDescendents of African slaves have experienced significant levels of disparities, says Margaret Mitchell, executive director of YWCA Greater Cleveland. “When you look, you see. Look at lead. This is a tragedy that has an effect.”

Margaret Mitchell, executive director of YWCA Greater ClevelandDescendents of African slaves have experienced significant levels of disparities, says Margaret Mitchell, executive director of YWCA Greater Cleveland. “When you look, you see. Look at lead. This is a tragedy that has an effect.”

She rattled off some of the determinants to make her case. “Infant mortality. The justice system. You see the impact.”

The YWCA and First Year Cleveland have been actively agitating in these spaces for a long time, Mitchell says.

“Racism must be addressed to improve birth outcomes,” she says. “We have a long history, but we’ve come to that point where it’s clear, systematic racism is affecting everyone.”

The summit will address how slavery’s legacy continues to impact America’s legacy, she says. “Why are we still experiencing what we see in 2019? Look at the number of police brutality cases in 2019, 2018, 1919, and 1918. And we know this has been systemic, and it keeps people afraid, disempowered, and confused.”

Cleveland is prime for this summit because some powerful work is already happening here, Mitchell says. “In unusual places, people are talking about race,” she says.

“Cleveland is a city of haves and have nots. You can look at the social determinants scales and rates of the impact of racism.”

Housing. Redlining. Education. Lead. Infant mortality, she said. “We perform poorly. We can easily build a list. The fact that we’ve normalized these poor outcomes, it’s unreal.”

What do we stand to lose? Mitchell says. “There’s a big economic cost to all this. Bridging the wage gap alone would have a positive impact on Northeast Ohio.”

This summit isn’t about being angry or threatening, it’s a time of truthful reckoning, she says. She asks attendees to bring a high level of humanity, to honor the ancestors.

“It’s time to get results. It’s time to build new systems that have equity,” she says.

Cleveland community leaders have made it clear they believe racism, both historical and contemporary, contributes significantly to the racial disparity in birth outcomes, says Dr. Arthur James, who heads the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University. They have been in talks with city and county leaders to consider declaring racism a public health crisis.

Project 400: Our Lived Experience Conference at the Wolstein Center in September 2019.In December 2018, the Canadian Public Health Association made such a declaration, James says, as did Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, in May 2019. As a consequence, First Year Cleveland and the Greater Cleveland YWCA invited representatives from Milwaukee County to the summit to discuss their declaration on a plenary panel.

Project 400: Our Lived Experience Conference at the Wolstein Center in September 2019.In December 2018, the Canadian Public Health Association made such a declaration, James says, as did Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, in May 2019. As a consequence, First Year Cleveland and the Greater Cleveland YWCA invited representatives from Milwaukee County to the summit to discuss their declaration on a plenary panel.

“We live in a research-oriented society that not only challenges us to ‘provide data’ but to also respond to what the data tells us,” James says.

“Just as a large body of knowledge informs us of the connection between poverty, unemployment, homelessness, undereducation, food insecurity, etc., and health outcomes, that same body of knowledge informs us that marginalization and racism adversely influence our health. The data is there, yet we have elected not to act on it, not to declare that racism harms many of our citizens, and that it has been doing so for centuries. It is my hope that making such a declaration brings more attention and focus on the harmful effects of racism and results in the implementation of many more laser-focused efforts to eliminate racism as part of our efforts to improve the public's health.”

To learn more about The 400 years of Inequity Summit, visit here. Registration closes Oct. 31 at 11:59 p.m.

Black Lives Matter protest in ClevelandCalls to Action

Black Lives Matter protest in ClevelandCalls to Action

What you can do to learn more about racism’s impact on public health and become more culturally sensitive:

1. Attend the 400 Years of Inequity Summit and other Project 400 events.

2. Research how the disparities mentioned in this article are impacting minority communities.

3 Support the work of The Diversity Center of Northeast Ohio.

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.