Follow the redlining to places the U.S. Census usually doesn't count

The U.S. Census Bureau makes it all sound so simple.

In preparation for the decennial 2020 U.S. Census, the federal government agency rolled out a comprehensive marketing plan this summer under the tagline of “Shape your future.” With new procedures that will allow citizens to respond online and by phone (as well as by the traditional standard of mailing back the form), the advertising describes the act of participating as “easier than ever.”

But not for everyone.

The facts are undeniable at the Undesign the Redline exhibit.Embedded in the census process is a population that is referred to as “hard to count”: geographical areas and population groups that have had previously low response rates. Want to find them? Well, that part is “easier than ever.” Just follow the redlining.

The facts are undeniable at the Undesign the Redline exhibit.Embedded in the census process is a population that is referred to as “hard to count”: geographical areas and population groups that have had previously low response rates. Want to find them? Well, that part is “easier than ever.” Just follow the redlining.

“Despite what some people think, redlining is still here and actively affecting people’s lives,” says Jennifer Lumpkin, civic engagement strategy manager for Cleveland Neighborhood Progress. “Without some serious action from a ton of stakeholders, it’s not going away anytime soon.”

Despite overwhelming evidence of Cleveland’s blatant history of redlining, a distinct lack of understanding and acceptance about this well-documented practice of inequity has hampered the needed remediation from taking place. Thankfully, a handful of passionate Clevelanders are working overtime to make sure each and every voice is counted, specifically those who have been historically left behind. With more than $675 billion set to be allocated for public services in Ohio based on the results of the 2020 U.S. Census, and with an undercount potentially costing the state a congressional seat, the stakes could not be higher for these individuals to succeed.

Redlining on Display

It is in your best interests to keep up with Devonta Dickey. With a boundless and youthful exuberance coupled with a keen command of the systems that have disempowered and disenfranchised underrepresented communities, Dickey has energy that is no less than infectious. Though his official title is advocacy and engagement coordinator for Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, these days his actual role is far more of guide. He has been working tirelessly to help people understand redlining’s impact in Cleveland as he ushers them through the “Undesign the Redline” exhibit at the Mt. Pleasant NOW Community Development Corporation.

“The evidence of redlining is irrefutable,” Dickey says as he gestures at the various sections of the exhibit covering the walls of the large conference room. “The trick is that it just needs to be translated in different ways for whoever walks into the room.”

To date, more than 2,000 individuals and 100 organizations have experienced the interactive displays, which cover everything from a timeline of redlining, to stories of those who have been affected by redlining, to alternative models of policies, practices, and entities that could undesign the legacy. The effects on those walking through the exhibit depend very much on the identity of the visitor.

“When people of color go through the exhibit, it can be a validating experience,” says Dickey. “They might not know the jargon or the terminology or the semantics of all of these systems, but they feel it and have been affected by it.”

For white people, Dickey describes a different reaction. To illustrate, he shares one example of a group of older white women from Shaker Heights who toured the exhibit a few months ago. When they arrived at the placard explaining the Underwriting Manual of the Federal Housing Administration that was specifically written with direct language that prevented loans from being insured to communities of color, one of the women resisted this history.

“She looked me in my face and tried to take race out of the equation, even though the language of the manual directly spoke to race,” says Dickey. “She was experiencing a form of cognitive dissonance as she needed a scapegoat to explain what she suddenly couldn’t unsee.”

By the end of the exhibit, Dickey relays that the woman was taken aback. She even apologized for her earlier comments, a testament to the sheer power of information on the walls.

By the end of the exhibit, Dickey relays that the woman was taken aback. She even apologized for her earlier comments, a testament to the sheer power of information on the walls.

That these walls are housed in the Kinsman neighborhood is no accident. Visitors need only look out the window between the first two sections of the exhibit to see a boarded-up, dilapidated house, visual evidence of the blight that redlining has enabled.

“Kinsman was not the ideal location by folks in power who wanted this to be closer to downtown,” says Lumpkin. “But we wanted to bring people of authority to this neighborhood who would not come here otherwise, so that they could see clear and illustrative examples of what redlining has done and continues to do.”

Mapping Inequality

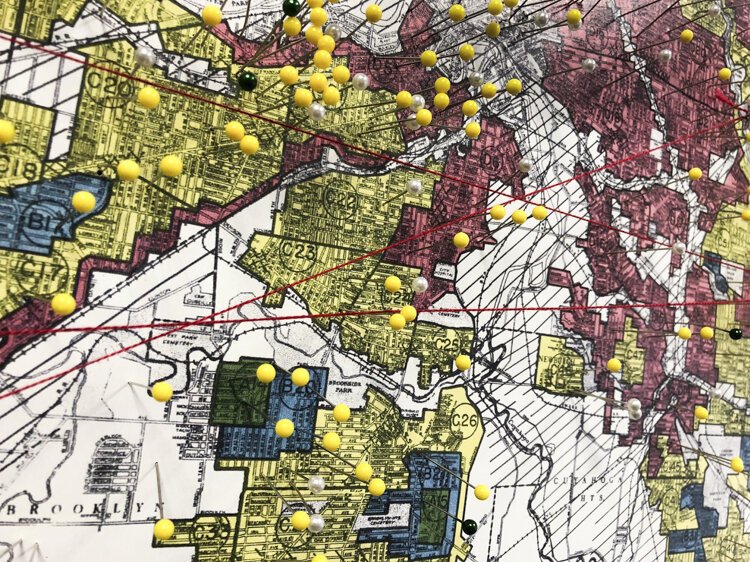

Perhaps the most stark and undeniable evidence of redlining at the exhibit are the color-coded maps. The sections where communities of color were segregated by redlining more than 80 years ago can be overlayed almost exactly with both low voter turnout and low census participation today. Whereas some might attempt to contend that redlining is a process of the past, the maps tell the story of clear effects in the present.

“A key part of this work is translating for people how redlining is still alive and well,” Lumpkin says.

Examples include a persistent lack of transportation, a higher sales tax in redlined areas when ordering things online, and businesses that simply will not deliver to certain neighborhoods. Lumpkin highlights that realtors continue to grade neighborhoods based on desirability, ratings that match up exactly with the redlining maps. She also stresses the importance of “digital redlining,” which she says is a key factor in maintaining the status quo.

“We were in the Buckeye area checking people’s voter registration, and I couldn’t get cell service,” says Lumpkin. “This is digital redlining, and it overlaps with the maps that have had historical redlining.”

Moving Forward

Though understanding the history of redlining is a critical prerequisite to understanding how to approach raising participation rates for the 2020 U.S. Census, knowledge of the past itself is not enough to accomplish this monumental task. Individuals must also understand the direct effects that the census can have on their day-to-day life.

“We have to be translators for one another on issues of funding, redistricting, congressional seats, and literal representation,” says Dickey. “From Medicaid to Head Start to school budgets to low energy housing assistance, there are a panoply of programs that use the census data to determine allocations, and we need to help people connect the dots so they understand the direct implications.”

Even with this understanding, barriers remain in place that prevent individuals in historically redlined neighborhoods from participating in the census. These obstacles are wholly less tangible. With a history of census data being actively used to restrict the equity of underrepresented communities (for example: the U.S. government’s internment of Japanese people during World War II), it should come as no surprise that many individuals are not leaping at the chance to partner up with an effort of the federal government. Messaging campaigns regarding the census aimed at the population-at-large simply may not resonate in these areas.

Even with this understanding, barriers remain in place that prevent individuals in historically redlined neighborhoods from participating in the census. These obstacles are wholly less tangible. With a history of census data being actively used to restrict the equity of underrepresented communities (for example: the U.S. government’s internment of Japanese people during World War II), it should come as no surprise that many individuals are not leaping at the chance to partner up with an effort of the federal government. Messaging campaigns regarding the census aimed at the population-at-large simply may not resonate in these areas.

“There is a real history behind this mistrust,” says Lumpkin. “There isn’t a physical impediment to mailing in the census. But there is a socio-emotional response, and we have to address it by making this work personal.”

With the participation period for the 2020 Census opening in just a few short months, Lumpkin and Dickey know they have their work cut out for them. They both acknowledge that the system cannot be changed overnight but also are quick to emphasize that nothing will change if people don’t act.

If they had their way, they would ask each individual and organization who visit “Undesign the Redline” to articulate how they supported—directly and indirectly—the process of redlining and what they will specifically do to undo it. But they also know that this approach can be seen as too “radical” an approach given that it’s an uphill battle to even convince many people that redlining still exists.

Still, Lumpkin and Dickey are undeterred. They know the history, and they keenly understand the colossal importance of the people counting that is about to take place in March. All they need is more people to stand with them.

“We need to be joined by more people calling out those things that people have gotten used to and then shouting out that they’re not normal,” Lumpkin says. “There’s so much more power sharing that could happen that would directly empower communities that continue to be affected by redlining. But it requires that people actually step up and make it happen right this second when it is so desperately needed.

“Undesign the Redline” is on display through the end of 2019 at Mt. Pleasant NOW Community Development Corporation. A traveling exhibit will open at Trinity Cathedral, 2230 Euclid Ave., Cleveland, on Monday, Oct. 7 and will remain open until Dec. 20. Private tours are available, and you can learn more by visiting http://www.designingthewe.com/undesign-the-redline/.

CLE Means We: Calls to Action

What can you do to learn more about redlining and how it affects the 2020 Census?

1) Visit "Undesign the Redline” and bring some friends with you.

2) Follow Cleveland Neighborhood Progress for the latest updates on Cleveland efforts to increase Census participation rates.

3) Read The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America for one of the best histories on redlining.

4) Use your newfound knowledge to introduce equity into the process via volunteering with the Census Bureau.

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.

About the Author: Ken Schneck

Ken Schneck is the Editor of The Buckeye Flame, Ohio’s LGBTQ+ news and views digital platform. He is the author of Seriously…What Am I Doing Here? The Adventures of a Wondering and Wandering Gay Jew (2017), LGBTQ Cleveland (2018), LGBTQ Columbus (2019), and LGBTQ Cincinnati. For 10 years, he was the host of This Show is So Gay, the nationally-syndicated radio show. In his spare time, he is a Professor of Education at Baldwin Wallace University, teaching courses in ethical leadership, antiracism, and how individuals can work with communities to make just and meaningful change.