One in 11 Ohioans has a felony conviction. Isn't it time they received a second chance?

CLE Means We: Calls to Action

Three things you can do to advance equity and inclusion after reading this article

- Read the Policy Matters Ohio study.

- Support the restaurants featured on the tour: Swerve Bar and Grill, EDWINS Leadership & Restaurant Institute, EDWINS Butcher Shop, and Jewellz Fine Dining in Cleveland Heights.

- Read the Racial Equity Sketch shared by the Commission on Economic Inclusion below for a better understanding of the challenges facing reentering citizens.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

The Commission on Economic Inclusion has launched a year-long storytelling project called Racial Equity Sketches, in which they demonstrate how racial equity is interconnected with issues affecting both the business community and our larger community. These fictional stories are meant to imagine what making “an equitable decision” could look like. Through them, they hope to reveal that equity is not always a major comprehensive strategy, but rather the compilation of many small, informed & thoughtful decisions.

Read "The Interview" below:

A door. And behind it, a new beginning.

Khyree’s mind flooded with positive thoughts as he waited in the hallway for his interview. To quiet his nerves, he focused on the granite name plate next to the dark mahogany door in front of him.

Judith Stine, Managing Partner.

Khyree imagined the word “Partner” next to his name one day. The thought gave him the confidence he needed in the moments before he heard a voice saying, “Please come in.”

“Ms. Stine, it’s an absolute pleasure to—”

“Please, Khyree, call me Judy! It’s a pleasure to meet you. I was seriously impressed by your cover letter.”

“Oh, thank you. It was very sincere.”

“I could tell. I’ve never seen a three-page cover letter—especially not for a clerical assistant position! It’s clear that you’re motivated and enthusiastic. To succeed here, though, you’ve got to be good at putting out fires. It’s a fast-paced, high-pressure environment. Can you tell me about a time you were in a high-pressure situation, and how you handled it?”

Khyree gave a polite smile and cleared his throat. He had practiced the answer several times, but his mind still couldn’t help but wander to that day seven years ago, the sound of his buddy Roger’s voice…

“Khy, you haven’t been drinking, right? Can you do me the biggest favor?” Roger explained to Khyree how his mother would get upset if his car wasn’t in the driveway by the morning.

Khyree agreed to help. Life is Good had just dropped, and a friend at the party gave him a tape. The 20-minute drive to Roger’s house was the perfect opportunity to listen.

Two songs in, Khyree noticed the gas was nearly empty. He pulled over at the closest gas station. He hadn’t been sitting for long before he heard noises coming from the car parked at the pump next to him. He lowered the volume. He looked over. His heart dropped.

“Please, please don’t hurt me,” a woman wailed in the passenger’s seat, as the man next to her gripped her neck. Sweat formed at Khyree’s temple as he contemplated what to do.

“Great question, Judy. To be honest, I think high-pressure environments are precisely where I thrive. In my first job on the floor of Procurus Manufacturing, I learned valuable skills in time management and conflict resolution…”

Khyree answered the first question exactly as rehearsed.

Judy looked pleased and jotted some notes. “Seems like you have a determined work ethic. Is there someone who inspires you to be that way? A role model?”

“Let me go, let me go…” the woman pleaded. The man did, but only to get out of the car. He walked over to her side and jerked her out. Khyree flinched as the man screamed in her face and pushed her head violently onto the hood of car. The woman faced Khyree now, looking directly into his eyes.

Khyree thought of his mother. The hardest-working, strongest person on the planet, who raised him and his sisters with the most graceful love he’d ever known. The day he saw Wallace lay his hands on her was the worst day of his life. She escaped that horrible relationship, but the few weeks that Wallace was home, Khyree promised himself he wouldn’t let anyone hurt his mother, or any other woman, ever again.

He got out the car. He walked over. He punched the man once. Twice. Over and over and over, until the man’s screams were drowned out by sirens.

Khyree pushed the memory out of his head, responding to Judy’s role model question with the one he had practiced with his job coach.

Judy was enthusiastic at the answer. “What a coincidence…my high school Government teacher was one of my biggest sources of inspiration as well. So Khyree, from your cover letter, I sense you’re very passionate about justice. Tell me where that came from.”

“I’m afraid we’re looking at something like six to eight years here, Mr. Higgins. The victim is still in critical condition. You mentioned to the cops that you were defending his girlfriend against him, but his girlfriend refuses to verify this. And the security cameras in the area didn’t capture the scene. To make matters worse, a significant amount of marijuana was found in the vehicle you were driving. We know the vehicle isn’t in your name, but you’d still be charged with possession. You also resisted arrest. There are a number of charges here. Unfortunately, your chances don’t look so great if you decide to go to trial.”

“I didn’t do anything wrong,” Khyree whispered under his breath. He was tired and hungry and had been held in jail for nearly three days before meeting with the prosecutor.

“According to the law, you did, Mr. Higgins. But you seem like a good person. I can work things out with you here. If you plead guilty, we can drop some charges, reduce the sentence. You could even have an early release. If you decide on a trial, you might have to spend months here waiting. Your family has indicated they’re unable to make bail. What do you think, Mr. Higgins?”

“I didn’t do anything wrong.”

“Mr. Higgins, I’m telling you because I know how this goes. A jury won’t agree with you.”

Judy’s eyes lit up as Khyree explained the papers he wrote for his classes at the local community college. “It’s great to hear that your interest in justice is rooted in so much research and reading. Any legal scholar you’d consider your favorite?”

“You better read this, son. But don’t let anybody catch you reading it.” Mike, Sr. handed Khyree a copy of Michelle Alexander’s book as they were walking back from their shift at the prison notebook factory.

Mike, Sr. had earned a reputation as "Lawyer Mike," imparting legal advice to anyone who would listen. He was nine years into his 20-year sentence, spending nearly every day reading and writing in notebooks he would bring back to his cell from the factory. Khyree enjoyed talking to Lawyer Mike, who struck him as the most scholarly and intelligent man he’d met. It was through conversations with Lawyer Mike that Khyree became committed to learning about the American legal system. At the end of his two-year sentence, Khyree would do everything he could to follow a career pathway in line with his newfound calling.

This interview was that chance, and as Khyree finished responding to Judy’s last question, he felt strangely calm. He had given this his absolute best shot.

“Khyree, I’ve been absolutely delighted by the opportunity to talk with you today. Based on what you’ve shared, it seems like you are exactly what we’re looking for.”

Judy smiled.

Khyree smiled too. “That’s great to hear. Does this mean I’ve got the job?”

“Almost. The only thing left to do is draw up the official paperwork, which you’ll need to sign. Oh, right. And there’s also a simple criminal background check. We’ll send you the link to that in our follow-up email. Anyone that works to protect the law has to have followed it, right?”

Judy spoke with a faint chuckle. Little did she know, across from her sat a man about to be denied a second chance, yet again.

To read the afterword for "The Interview" and more information and recommended reading suggestions, please click here.

Your spirits will be instantly uplifted within mere seconds of sitting down with Karen McAlpine. The 38-year-old mother of three radiates a positive energy that is no less than supremely infectious. Currently, McAlpine is seeking an opportunity to channel her gift of an inspiring personality into a career where she can help people, make a difference, and somehow give back.

Her ever-present smile only falters when she reflects on her experiences trying to secure such a job. “Society just won’t let me,” sighs McAlpine.

Her ever-present smile only falters when she reflects on her experiences trying to secure such a job. “Society just won’t let me,” sighs McAlpine.

Back in 1999, McAlpine started hanging around with what she now calls “the wrong crowd.” She found what she thought was a quick way to make money, but was just as quickly arrested for trafficking crack cocaine.

The prosecutor opted to turn the possibility of one criminal charge into 15 against McAlpine, and the then 19-year-old was sent to the Ohio Reformatory for Women in Marysville. Upon her release two years later, she was determined to turn her life around.

“I never again want to be away from my children, from my family, from my religion,” says McAlpine. “I’m now on 15 years without a felony, but even though I try to be hopeful about finding a great job, the reality of constantly getting rejected has me feeling like I’m the hamster on the wheel.”

By the numbers

McAlpine’s experiences are not uncommon. In fact, in light of her steady—if low-paying—employment with a telemarketing company for years, she stands as a nigh-fortunate outlier to those attempting to return to employment after a felony conviction.

The latest research from a Policy Matters Ohio study paints a disheartening portrait of the job prospects for those returning to public life from incarceration. The most stark finding is that around one in 4 Ohio jobs is blocked or restricted for those with a conviction. (To be clear, these aren’t just 1.3 million random jobs, but ones that, on average, pay $4,700 more and are growing at twice the rate of other jobs.)

Toss aside the merits, drive, or personality of the applicant—even though recent research has found people with criminal records have a much longer tenure and are less likely to quit their jobs voluntarily. In conjunction with some 850 laws and administrative rules, myriad employment opportunities are deliberately put just out of reach of those with a criminal conviction.

The economic reality for the estimated one in 11 Ohioans with a felony conviction is often a lifelong debt to society that hangs over some of their heads long after society declares that their debt has “officially” been paid.

“The system itself needs to change,” says Crystal Bryant, Director of the Cuyahoga County Office of Reentry. “So much of understanding the idea of ‘reentry’ is focused on definitions. We need to instead be focused on generational poverty, structural racism, and a host of other issues in the ecosystem that can be a barrier to employment after individuals return from being away.”

“The system itself needs to change,” says Crystal Bryant, Director of the Cuyahoga County Office of Reentry. “So much of understanding the idea of ‘reentry’ is focused on definitions. We need to instead be focused on generational poverty, structural racism, and a host of other issues in the ecosystem that can be a barrier to employment after individuals return from being away.”

Celebrating momentum

In an effort to highlight the ways the Office of Reentry and various community partners are supporting successful post-incarceration, this week marks Cuyahoga County's second annual Reentry Week. Scheduled programming ranges from a Legislative Breakfast with local and state elected leaders to discuss removing barriers for returning citizens, to panel discussions on housing discrimination, to the third annual Breaking Down Barriers Hiring Event featuring on-site interviews and community resources for attendees.

“Reentry Week is about showing people that commit to the promises we make as a society to those coming home,” says Bryant. “We want people to see the week as an opportunity to come together, create changes, but also to celebrate. There are people doing really, really well out there. It’s not all doom and gloom!”

One of the highlights of Reentry Week was the Taste of Cleveland Reentry Restaurant Bus Tour, an opportunity to help raise the profile of local cuisine from businesses owned, operated, or staffed by returning citizens. Restaurants included Swerve Bar and Grill in Shaker Heights, EDWINS Leadership & Restaurant Institute and EDWINS Butcher Shop in Shaker Square, and Jewellz Fine Dining in Cleveland Heights.

Swerve Grille founder Tony Jones has no criminal background, but growing up in the inner city, he had a front-row seat to the employment struggles those with criminal records face. Jones has hired at least eight previously incarcerated men to help with dishwashing, food prep, and restaurant maintenance, and the restaurant is currently qualifying to be part of the county's reentry program.

“It’s about being fair, not shutting them out and providing a second chance,” says Jones.

Bryant agrees, “We want to bring recognition [to] and celebrate these owners and their successes. We have to acknowledge and recognize that people with a background can and do succeed.”

Taking legislative action

One familiar face on the bus tour was Representative Stephanie D. Howse of Ohio’s 11th District. The daughter of former State Representative Annie Key, Howse relays that she has been motivated to look at criminal justice reform by both the community in which she was raised, as well as her mother who always had a passion for people society considered “throwaways.”

“Through my lived experience, I’ve seen the devastating impact of criminal justice not rehabilitating people,” says Howse. “Families are taken apart without regard to mental and emotional impact, and then people are just expected to go back to employment after? It just doesn’t work like that.”

Representative Howse is passionate about the reentry process beginning when an individual is in the care of the state, assisting them to more solidly set up the outcome that they might be in a better position after incarceration than before. She cites the importance of Senate Bill 3—an attempt to reform drug sentencing laws, introduced in February and currently being debated in committee—as integral to a systems approach in looking at reentry.

“I have to remain encouraged—even with this new administration—at how people are looking at certain aspects of the criminal justice system,” reflects Howse. “If we try to take a more public health lens and have our sentencing aligned with the facts and science of addiction, it can be a thoughtful and intentional model for addressing, among many things, reentry.”

Moving forward

One of Cleveland's most trumpeted reentry success stories has come out of the kitchen of EDWINS Leadership & Restaurant Institute in Shaker Square. Founded by Brandon Chrostowski, the efforts to provide formerly incarcerated adults with hospitality and culinary training have been both widely covered and—in the case of a documentary on their work—Oscar-nominated.

The attention has also caused the unintended side effect of some community partners feeling like they need to provide the same all-encompassing level of reentry services provided by Chrostowski and his extraordinary list of sponsors.

The attention has also caused the unintended side effect of some community partners feeling like they need to provide the same all-encompassing level of reentry services provided by Chrostowski and his extraordinary list of sponsors.

As the EDWINS model is inspiring for all—but may be unrealistic for most organizations—Bryant suggests businesses and organizations to resist the urge to try to emulate this high-profile example and instead “stay in their lane” to provide the best possible model to support reentry.

“If you’re good at workforce, be great,” says Bryant. “If you’re a housing provider, perfect your process, include those who have experienced reentry in your facility, and create a continuum of care for them.”

For her part, Karen McAlpine is just trying to stay positive. She admits to sometimes feeling bitter about how she was treated by the judge 18 years ago and other times feeling extraordinarily discouraged by job opportunities that suddenly fall apart during the background check process. But she doesn’t let it stop her from wanting to make a difference, particularly for those who have been through what she has survived.

“If I can meet that one person like myself whom I can help, then it all will have been worth it,” says McAlpine. “People are perishing from a lack of knowledge, and not everyone is as strong as me. There has to be more that can be done to support those who are just trying to build a great life after their debts have been paid.”

Epilogue

In providing information for this piece, Karen McAlpine and Crystal Bryant met in person for the first time sitting at a table in Gypsy Beans in Gordon Square. As McAlpine described her difficulties with finding a fulfilling position, she expressed a desire for more networking opportunities.

Bryant immediately interrupted her.

Bryant immediately interrupted her.

“Are you on my e-mail list?” Bryant asked.

“I don’t think so,” McAlpine responded.

“I have the perfect job for you,” Bryant said without pause and immediately pulled up a position description on her phone.

McAlpine's already large smile somehow got even bigger.

“God is good,” she beamed.

“So is networking,” responded Bryant.

They both shared a laugh as McAlpine entered in her e-mail address to Bryant’s phone, promising to apply for the position straightaway.

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.

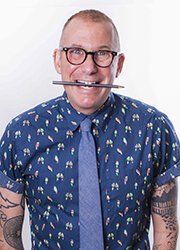

About the Author: Ken Schneck

Ken Schneck is the Editor of The Buckeye Flame, Ohio’s LGBTQ+ news and views digital platform. He is the author of Seriously…What Am I Doing Here? The Adventures of a Wondering and Wandering Gay Jew (2017), LGBTQ Cleveland (2018), LGBTQ Columbus (2019), and LGBTQ Cincinnati. For 10 years, he was the host of This Show is So Gay, the nationally-syndicated radio show. In his spare time, he is a Professor of Education at Baldwin Wallace University, teaching courses in ethical leadership, antiracism, and how individuals can work with communities to make just and meaningful change.