Inside MOCA's compelling new Alexis Rockman: The Great Lakes Cycle exhibition

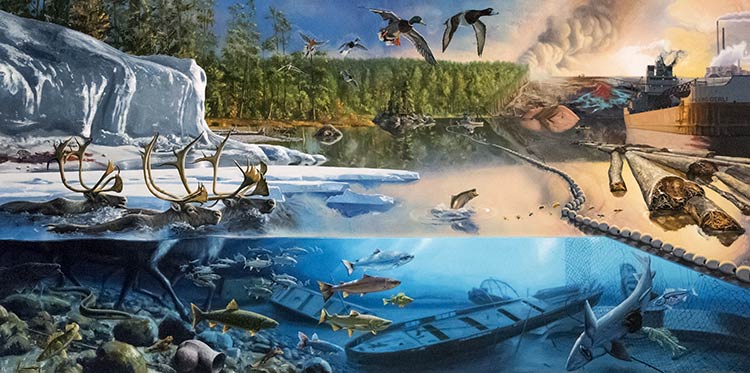

At the heart of Alexis Rockman: The Great Lakes Cycle—currently on exhibition at Cleveland’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA)—are five mural-sized paintings depicting the Great Lakes’ ecological history, evolution, and challenges.

The vibrant oil and alkyd paintings consume viewers, drawing them into colorful but concerning worlds devoid of continuity of time or specific place. It’s the past, present, and future makeup of the lakes on which the exhibition focuses: invasive species; mastodon bones left over from the lakes’ inception about 14,000 years ago; a genetically modified cow grossly mutilated; and byproducts from the agriculture industry feeding tributaries that will birth toxic algal blooms.

Every animal, drone, and glacier is an intentionally placed lesson or commentary, all of which is neatly outlined on informational keys that correspond with each piece.

“Even though I grew up in New York (City), I feel like it’s my own backyard,” Rockman says of the Great Lakes. “It’s one of those things we take for granted. There’s a lot to cherish in the lakes and what’s left of so-called nature.”

When the Grand Rapids Art Museum commissioned Rockman for the project in 2013, no one could have predicted the current political atmosphere—with attempts to end funding for The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, which aims to protect the lakes, as well as endless algal blooms and a statewide debate on whether or not to legally define Lake Erie as “threatened.” Deregulation of industry and a rolling back of environmental protections have become common themes nationally.

Megan Lykins Reich, MOCA’s deputy director, says that when the museum agreed to show the exhibition four years ago, the work hadn’t even been created yet.

“We sensed the relevancy for our community, knew that Alexis would produce something incredible, and estimated that the work—given its large-scale, figurative nature—would captivate a broad audience," says Reich. “We had no idea that the show would open just as climate change and environmental change have risen to such urgency in international political debate and policy-making.”

And who better to highlight those issue than Rockman? After all, the impact of climate change on what's left of the world's natural spaces has been a common theme in his work—which has been exhibited both nationally and internationally since the late 1980s. Through the lens of his extensive travels and unrelenting interest in science, Rockman connects the natural world with the systems of capitalism and consumerism, providing glimpses of where our culture might lead us, and from where we came.

The 2009 film adaptation of Yann Martel’s "Life of Pi” relied heavily on hundreds of sketches Rockman created, depicting real and imagined species that lurked in the sea on which the main characters' adventure unfolded. Bright against black paper, the sketches show luminous species and organisms silent in the deep sea.

Lake effect

Out on the Grand River, while immersing himself in research and a tour of the region, Rockman recalls he noticed endless ripples; large fish rolling around in the mud like fat, happy pigs. They were actually invasive carp that had taken over the river.

“There was nothing else there,” Rockman says. “I was shocked at how much of a desert it was in terms of biodiversity.”

It was small moments like these that inspired Rockman to pinpoint five subject areas, which would later become the exhibition’s main murals. “Pioneers” focuses on the water itself, and the plants and animals that have made their way into the lakes. “Cascade” looks at the effects of human activity, while “Spheres of Influence” looks at how globalism has affected the lakes. “Watershed” deals with land around the Lakes and its impact, and “Forces of Change” reflects on the challenges and possibilities for recovery in the post-industrial age.

A collection of large-scale watercolors and 30 field drawings created with organic matter collected from around the region are also featured in the show. “There were a lot of ideas that I didn’t have a place for in the paintings,” says Rockman.

These paintings—which could be considered footnotes of sorts—include a chimera made out of invasive species; an ice fisherman under the Northern Lights made from microscopic matter native to the bodies of water; and an Upper Peninsula moose.

“Everyone needs a moose,” Rockman insists.

Alexis Rockman discusses his work at MOCA on opening nightDigging in

Alexis Rockman discusses his work at MOCA on opening nightDigging in

As typical of Rockman's work, there are also more complex stories represented in the watercolors. In “Bubbly Creek,” fish-like creatures grimace upwards toward a grayscale landscape above dominated by a transparent rooster, hovering over the water. The piece references a tributary of the Chicago River that was so clogged with beef fat from discarded carcasses that a rooster could walk on its surface. According to Rockman, the creatures swimming are actually caricatures of the political power players in Chicago at the turn of the 19th century.

Much of what is depicted in Rockman’s work conjures the past, or what the future may look like as the result of current trends and policies.

His mother was an archaeologist, so Rockman grew up surrounded by natural history. Though Rockman wasn’t interested in following in his mother’s footsteps, he acknowledges that he “ended up doing something similar. I guess you could say these paintings are the archeology of the future, because most of these creatures will not be here; they’ll be either eaten or extinct for other reasons”—a fact that enrages Rockman.

He laughs when people comment on how brightly-colored The Great Lakes Cycle paintings are; how vivid his blues are.

“If you have blue water in the Great Lakes, it means it’s an ecological desert because all the life’s been sucked out of it,” he says. “It’s a red flag.”

The next wave

The exhibition, which came to Cleveland after being shown at the Chicago Cultural Center, will also appear at the Haggerty Museum of Art of Marquette University; the Weisman Art Museum at University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; and Flint Institute of Arts.

Rockman is already busy following new leads for follow-up projects—and even a few Cleveland-specific ideas “if the funding is there.”

There are scheduled lectures and educational events at MOCA throughout the length of the show, which runs through January 27. Visitors can enjoy the museum for free this Saturday, November 3rd, with “First Free Saturday” (sponsored by PNC Bank) from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on Saturday, November 17, local artist Ryan Dewey will share his thoughts on The Great Lakes Cycle exhibition during “Artists on Art” at 2:30 p.m.

MOCA’s Reich says that she hopes the exhibition and related programming will “create a sense of wonder and respect for the significance of the Great Lakes” and “remind us of the virtue and unparalleled value of the Great Lakes—one of the world's most precious natural resources—while also forcing us to acknowledge how our practices influence its evolution and often devolution. It is work that seduces you only to assert your culpability. You want to look away, but you can't. You are implicated. The question really becomes, 'What do you do with this awareness?'"