5 key takeaways about school improvement in Cleveland

Four years ago, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) was in pretty bad shape. “We had made it to ‘continuous improvement’ status [with the Ohio Department of Education], then fell back to ‘academic watch’ and then to ‘academic emergency,’” recalls CEO Eric Gordon. “We were essentially academically and financially bankrupt.”

Cleveland is home to the nation’s second school voucher program, which allows families to use public funds to attend private and parochial schools, even some outside the city. “The fact was people were choosing, and we had to get into the market so people would choose us as well,” says Gordon.

Leaders knew something had to change. “We did not have a systematic strategy,” Gordon explains. “In an effort to rethink what the schools would look like, we started the Cleveland Plan in February 2011.”

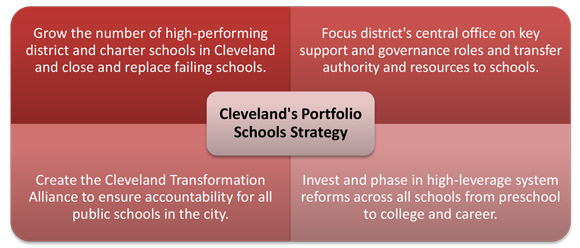

Mayor Frank Jackson was a driving force behind the plan, and he outlined to the public the need for drastic improvements in the district. After legislators were convinced to take action, Ohio Governor John Kasich in 2012 signed into law Cleveland’s Plan for Transforming Schools. The district moved to a portfolio model, based on research by the Center for Reinventing Public Education (CRPE). The Cleveland Plan outlines an agenda to provide school choices driven by demand, improve test scores and graduation rates, create more high-performing schools, and closes failing schools.

While Gordon says there are opponents of the portfolio model, which has been around for 20 years, it suits CMSD well. “There are critics of the portfolio model who argue that it’s not fully research-based,” he says. “But we had a model for years and years that wasn’t working.” The portfolio model provides a variety of school options and choices to suit each individual student’s needs.

The nonprofit Cleveland Transformation Alliance was created in 2012 to execute the Cleveland Plan and monitor the district’s progress toward reaching its goals. The Alliance, a collaborative partnership between CMSD, charter schools and nonprofits, aims to make sure CMSD students get the best education, suited for their needs, in the best schools. The Cleveland Plan ultimately will eliminate the system’s failing schools, improve test scores and graduation rates and implement system reforms across the board.

This past June, the Transformation Alliance released its first Report to the Community on the Impact and Implementation of the Cleveland Plan – tracking the progress made since 2012, looking at long-term goals and making recommendations for continued improvements.

The report is based on the most recent data available -- from the 2013-14 school year. Data from the 2014-15 school year data should be out in January, and the Alliance will issue another report then. The Alliance plans to continue to issue progress reports as more data becomes available.

The Alliance’s report indicates that while some progress has been made in improving the schools, there is still a long way to go. The infrastructure is in place and there are already signs of better management, better grades and better schools overall. While it may have taken some time to get rolling, conditions are now right for some faster changes.

“The first couple of years the district really spent time to put the right conditions in place to have the best schools,” says Gordon. “But with that initial slowness in getting conditions right we are now poised to move this system much more quickly.”

Here are five main takeaways from the report.

- Individual Schools Need More Autonomy

The central office was literally distanced from the day-to-day operations of schools. “It left very little decision-making capacity at the individual school,” says Piet van Lier, the Alliance’s director of school quality, policy and communications.

Instead of using a “one size fits all” approach, the central office is now moving into more of a hands-off role, giving individual schools the autonomy they need. “It’s not just autonomy, there is a really massive transformation here,” says van Lier. “The central office will have very little decision-making capacity at the individual schools. The district is trying to move into a support role.”

Gordon adds, "I don't think there’s a superintendent out there who can sit in this office downtown and know what the students need. We’re re-oriented. Instead of being a top-down directive organization, the schools deploy the resources and write the plans.”

This shift includes 48 percent of the district operating budget being controlled at the school level. Principals and teachers have greater latitude in determining school hours, programs and curricula. Nine schools piloted autonomy programs in the 2012-13 school year, and all schools were given autonomy starting in July 2013. Close supervision continues with schools deemed low-performing or failing. “Each school really knows its students and can react on the ground,” explains van Lier. “The district is putting that autonomy where people really know the student best.”

Campus International School

Campus International School

The autonomy has resulted in some unique alternatives, such as Campus International School, which is Cleveland’s only international baccalaureate school. Located on the Cleveland State University campus, the school teaches Mandarin Chinese to all students. This year Campus International houses students in kindergarten through seventh grade, and will add a grade each year until it runs through high school.

Another example is Tremont Montessori, which takes the Montessori approach in Pre-K through eighth grade, and Paul L. Dunbar School, which has begun incorporating an arts-infused curriculum. When Principal Sofia Piperis took the leadership reins last year, the school was using an enrichment model of learning to encourage critical thinking among a small group of gifted and talented students.

Piperis soon found that the model worked for the entire school but the students needed more engagement to get excited about learning. So she switched the model to the arts – from the visual arts to dance, music and writing. She took her student-based budget and, working with the Progressive Arts Alliance, implemented a 10-week program that combines sciences with the arts.

Progressive Arts Alliance CMSD partner workshop

Progressive Arts Alliance CMSD partner workshop

“We want our students to become engaged in learning,” explains Piperis. “We want to encourage lifelong learning.”Dunbar also received grants to help fund the curriculum. The school autonomy allowed Piperis to implement a curriculum most appropriate for the Dunbar students.

“It’s given us the flexibility to design a piece of what really works for our students,” she says. “This is the model we needed here.”

- Improvements Take Time to Reflect Success

While the latest numbers show an 11 percent drop in the number of students attending schools deemed “high performing,” there was also an 11 percent drop in the number of students in failing schools. Mid-performance schools saw a 39 percent increase, while low-performing schools saw a 29 percent increase.

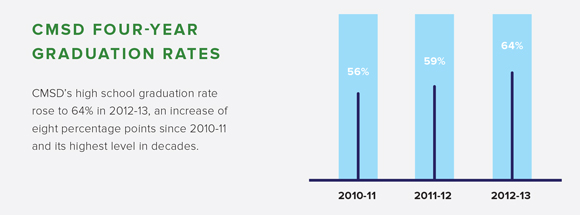

But van Lier stresses that it will take some time for the statistics to reflect the progress made in grades, graduation rates, and test scores. “It isn’t going to show up immediately in test scores,” says van Lier. “It takes a year or two for test scores to show up to where we’d like to see them. There’s a lag time between changes that are made and what we hope will show up in test scores and other state ratings. This is particularly true for graduation rates, since ninth graders entering new schools won’t contribute to improved graduation rates until four years later.”

An additional issue with reports reflecting any improvements is the fact that the Ohio Board of Education has changed its assessment methods three times in three years. As the assessments have become increasingly stringent, the improvements in test scores and graduation rates may not be as obvious.

Gordon points out that there is a five year lag time in state reports, especially in the high schools. “For high schools, one of the ways to improve their [state] grades it to improve their graduation rates,” he says, adding that this year’s incoming freshman obviously won’t be reported in the graduation rates. “But we have been making gains to show what to expect.”

Improvement could show up as early as the upcoming school year.

- The Alliance is Now Fully Functional, with an Eye on 2019

Of the nine high-performing CMSD schools, six were fully enrolled at the start of 2014-15. Of the two high-performing charter schools, both were fully enrolled at the start of 2014-15. “We’re making sure kids are going to the high-performing schools,” says van Lier. “We’re making progress in the right direction.”

CMSD identified two low-performing K-8 schools – Buckeye-Woodland and Paul Revere – for closure at the end of the upcoming school year, and is phasing out SuccessTech High School. In the 2013-14 and 2014-15 school years 23 of CMSD’s poorest performing schools were targeted for corrective action and added investment -- using an intensive community wraparound strategy that is supported by United Way of Greater Cleveland and in partnership with local service agencies.

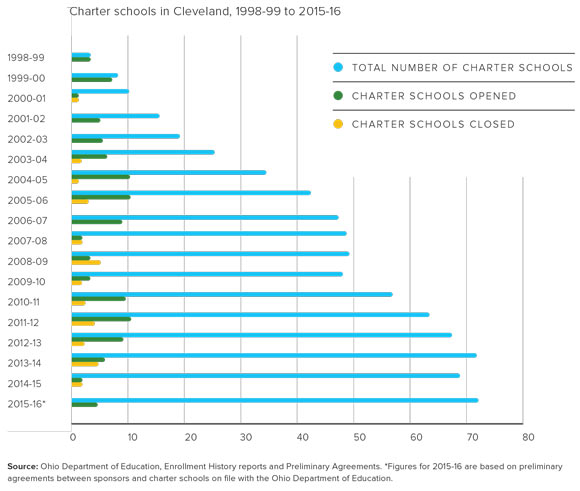

The wraparound strategy includes services like academic supports and enrichment, family engagement, parent leadership and adult education, year-round enrichment programming, access to social services and life skills training. Six charter schools have also been closed for academic or financial reasons.

“The fact that kids are filling up the better schools is good progress” says van Lier. “And the number of kids in schools rated as failing has dropped.”

The CMSD has added five new high schools and added grades and seats at some of the high performing school since 2012, and four new charter schools have been created based on high-performance models.

- CMSD and Charters Working Together

That collaborative approach has resulted in some unique partnerships. For instance, Near West Intergenerational School, one of the top-rated K-8 schools in Cleveland, operated for several years out of Garrett Morgan. Near West was the first charter school in Ohio to be co-located in a district school. Now the school leases space from CMSD in the old Kentucky School next door to Garrett Morgan.

Near West Intergenerational School

Near West Intergenerational School

And, starting with this school year, Citizens Academy Southeast is co-located in the south wing of Whitney M. Young.

Under CMSD’s open enrollment policy, parents and students can choose any school within the district. The idea is to get students into schools that best meet their needs, as opposed to the ones closest to their homes. Those charter schools that partner with or are sponsored by the CMSD only add to the portfolio approach to developing a good school district, says Alan Rosskamm, CEO of Breakthrough Schools and Alliance board member.

Breakthrough touts the highest-performing performance record among Cleveland charter schools. The charter schools under the district umbrella receive a portion of the tax levy money collected from property taxes and their performance numbers are included in state reports.

“What is unique about Cleveland and unique about the Cleveland Plan is the strong collaboration with the district and charter schools,” Rosskamm says. The cooperation between CMSD and the charter schools is so unique it earned the district a $100,000 one-year planning grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to expand the number of high performing schools in the district. The grant will also help improve education for special needs students and students who are learning English.

“The key is for parents to make good choices and use their resources,” Rosskamm explains. “Charters are designed to provide options and choice for families. It’s about getting children in schools that are right for them.”

- Ongoing Trust and Support Makes the Difference

The levy will be up for renewal in 2016, and passage will be critical to the Alliance’s continued progress. "The levy renewal is important for work on the Cleveland Plan to continue,’ says van Lier. “Cleveland Plan goals run through the 2018-19 school year, so the levy in 2016 isn’t the end, it’s a step along the way. Without levy renewal, it will be that much more difficult to keep making progress toward longer-term goals.”

Moving Ahead

While the Transformation Alliance has made significant strides in executing the Cleveland Plan, van Lier stresses it will take time. “We’d love every school in Cleveland to be an excellent school,” he says. “But that’s not going to happen right away. There are some signs of progress and some miles to go.”

The Alliance plans to push onward. “With the end goal of ensuring that all Cleveland children can attend quality schools, the Alliance’s top priority is making sure that all stakeholders intensify their work toward that goal,” says van Lier.

“More specifically,” he adds, “this work includes developing or strengthening targeted support and intervention strategies for all schools, both district and charter, depending on their current performance; closing or phasing out schools that are not improving; recruiting and training strong leaders and teachers for all schools; expanding the effective use of data and technology; increasing parent and community awareness of and demand for quality schools; and fostering district and charter collaboration.”