a conversation with scott raab, bona fide product of Cleveland

David Lee Roth once sang, “You got it tough? I’ve seen the toughest around.” He might as well have been talking about Cleveland. Strong and silent, this city keeps its cuts, bruises and dirty laundry to itself. Of course, a few japes have been known to land: Borscht Belt-styled gags and the occasional Hollywood cheap shot. Cleveland has always managed to shrug it off.

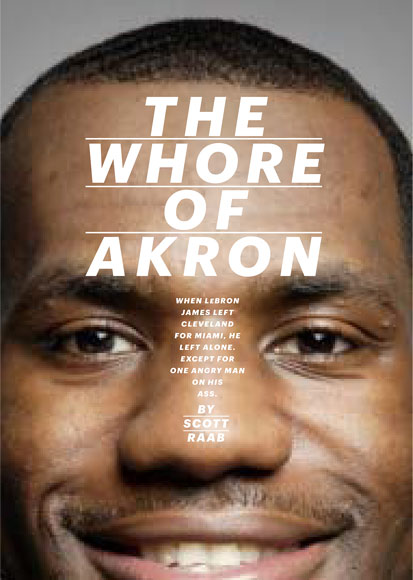

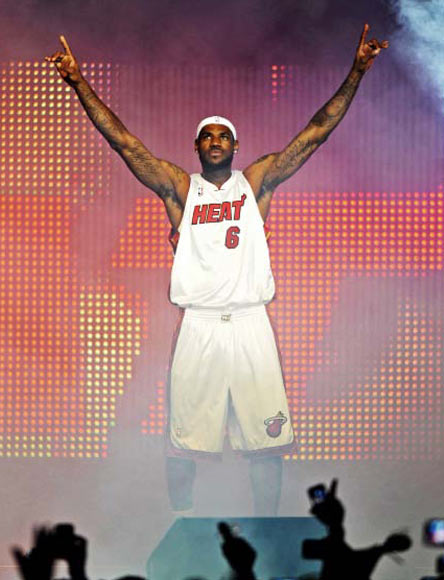

Yet not so long ago, our civic woes were aired worldwide when a certain LeBron James, the self-appointed King of the NBA, bobbled his crown and missed out on a 2010 championship ring. Following this flop was “The Decision,” the media madness that, to borrow a LeBronism, lit the pop-culture world up like Vegas. Like some jilted lover’s plight made public, Cleveland’s long history of the Eternal Stick and Its Short End made worldwide headlines. The whole fooferaw made for some sweet sympathy -- but it also made for a lot of rubbernecking. It made a lot of proud Clevelanders stick up for their home; it also made a lot of them mad as hell.

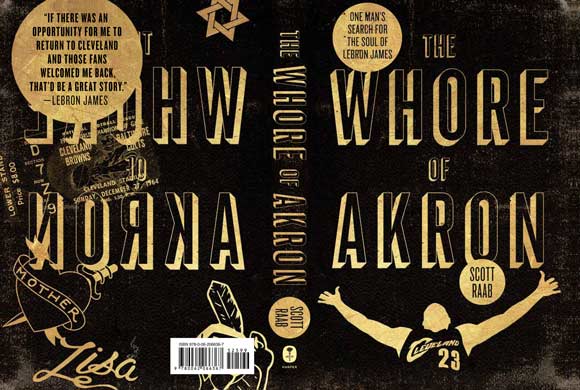

One of those Clevelanders was (and is) Scott Raab, whose book on LeBron James and his aftermath, The Whore Of Akron: One Man’s Search For the Soul Of Lebron James, is unleashed upon the world next week. In this bitingly funny, personal book, Raab follows the fall of the man who would have been King, while exploring the notions of victory, defeat and fanhood. And the fact that you just don’t (can't, really) mess with Cleveland.

Eons ago, Raab was a Cleveland State grad who got into the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop. In the early 90s, he began writing for GQ and Esquire. He’s been widely anthologized, wrote a bunch of celebrity profiles (which became a book, Real Hollywood Stories), and still cranks out prime content for Esquire, for which he is writer at large.

Even longer ago, Raab witnessed the Cleveland Browns whomp the Baltimore Colts in the ‘64 NFL Championship -- the last time a major sports team in this town won the ultimate prize. That experience -- Raab carries his ticket stub from that game at all times -- plus a lifetime of others -- he has Chief Wahoo tattooed on his skin -- makes him classically, permanently Cleveland.

That’s why Raab was so struck -- and enraged -- by Lebron’s failure and flight. How could you just up and leave home? A resident of New Jersey, Raab rhapsodizes over Cleveland like a Biblical prophet tossed out of Jerusalem. It’s a home tarnished by time, but burnished by hope. LeBron James, according to Raab, gave up on his home.

FW: When did you start to suspect that LeBron might leave?

SR: I started meeting with the Cavs’ front office after the 2009 playoff series, when Cleveland lost to the Orlando Magic. I figured GM Danny Ferry, coach Mike Brown, and LeBron, they were on their way out. The next season was going to be championship or bust, and I wanted to write a “happy” book about their eventual triumph.

Now, I had misgivings about LeBron, ever since that Yankees ballcap incident. I was pissed off, but I reconciled to root for him despite that. Time passed, and he kept getting better, and the team was getting better, too.

But as time passed, there were some strange things. There was no real relationship between LeBron and the Cleveland media. Some of the guys who covered the team waited years for five minutes of one-on-one time -- and didn’t get it. LeBron just did what he wanted to do. It was puzzling, everyone catering to what he wanted to do, and even Mike Brown saying, “I’m grateful LeBron lets me coach him.” I don’t know if I’d ever heard a pro coach talk that way.

So after LeBron fell apart in the 2010 playoffs against the Boston Celtics, I started blogging about where he might end up in July. Around that time, things started getting ugly. [Cavs owner] Dan Gilbert went after Tom Izzo, the coach from Michigan State, and LeBron refused to take any calls. It struck me as utterly bizarre. Clearly the behavior was of someone who didn’t care for the organization, someone who had no ties. I got increasingly bitter about it.

Are you still bitter about it?

I thought the end result of this story was going to culminate in one of the greatest athletes ever born in Northeast Ohio winning a championship... in Miami. He didn’t. And among my ideal scenarios is that LeBron plays 15 years and never wins a championship.

Sports generates a lot of strong emotions around here. Why do you think sports are so integral to Cleveland?

I think you could come up with some sociological reason for it. Northeast Ohio is so rich with football history; if you go to Cooperstown, [home of the Baseball Hall of Fame,] you see that the Indians have had a rich history here for over 100 years. But I think it comes down to this: Cleveland has lost an enormous amount of population and prestige. One of the last things that Cleveland has to hold on to, as a big city that makes a difference, is these teams.

On one of my last trips to Miami, I saw the Cleveland Orchestra during their winter residency. They were amazing. That orchestra is one of the greatest in the world, and that’s no small thing. But in popular culture, sports counts. These major league teams are a big way of how people inside and outside the city define Cleveland. I know stadiums don’t always bring jobs, but it can lead the way to making people feel good about their city.

Sports is a language spoken around the world. In terms of cultural currency, LeBron made Cleveland a place of note in China. People paid attention by the millions. I’ve got an admiration for Michael Symon and Harvey Pekar, but they just don’t have that kind of scale. The Cleveland Clinic is great, but I’m sorry, in terms of reach, it’s not the same. People remembered Cleveland because this amazing athlete plied his craft there for seven years. That’s just the reality of it.

If someone who isn’t from Cleveland reads this book, what do you hope they’ll get from it? Does Cleveland's tale possess some universal qualities?

That’s an interesting question. No matter where a person’s from, you try to figure out what are your values. How do you define yourself? How do you live your life? Those are important questions. And they transcend any one aspect of our day-to-day existence, but also embrace those aspects.

I feel strongly about Cleveland -- especially the history of Cleveland for the past 50 years. I’m a Cleveland State University grad. I was always a fan of the city, even though I saw the city and its image falling apart, and I saw the teams failing.

I often say that Cleveland taught me more than I could ever repay. It taught me lessons about resilience -- you know, all those clichés about heart, about not giving up, not pointing fingers, but to move forward to carve out a life, to do the right thing when people give you shit. Cleveland taught me all those things. It’s a wonderful place to be from.

While we’re on the topic of Cleveland, what memories do you have of it while you lived here? What were the places that, in your opinion, defined your experience of Cleveland?

I grew up as someone who grew up and went to Euclid Beach, stayed at Cedar Point at the Breakers in Sandusky. I went to elementary school and junior high in Cleveland Heights, and high school in Mayfield. Worked at Meyer Miller shoes on Cedar and Lee -- it’s gone now -- and I tended bar at a couple places on Chagrin, too. One was a Stouffer’s restaurant called the James Tavern, which had a colonial theme. I had to wear knickers.

I started as a freshman in the dorms at Case in ‘70 and ‘71, and dropped out of Case after my freshman year, because that’s when I started drinking and drugging very heavily. I wasn’t really college material at that point. I started at Case in 1970, and by the time I got my bachelor’s, it was 1983, from Cleveland State. One of my tours of duty at Cleveland State was during the Frankie Spisak years. He was a cross-dressing Nazi murderer, remember? I met my first wife at the Shire, the campus bar. Things have changed a lot since then, and for the better. I owe a lot to Cleveland State; it was a place I got to feel good about myself as a student of literature. I got out of it what I put into it.

Back then, Cleveland Municipal Stadium and Cleveland State were the only two places where East and West Siders actually had a chance to commune. From the age of 13 or 14, Municipal Stadium was the best place in the world for me. I didn’t have family around, screaming at each other, screaming at me. It was a place of refuge and relaxation. I spent so many of the best hours of my young life for baseball in Section 33 or 34, lower deck, left field line, down by the foul pole, in $2 general admission seats. I had an uncle who had season tickets to Browns games, and in those days, the Browns were a model of sports excellence. People said that it was always dank and windy, but to me, the Stadium was just home.