skullpture artists: startup's implants restore patient's head shape following traumatic event

Perhaps nothing more intimately represents a person's identity and sense of self than one's face.

We look at it in the mirror every morning, its expression lets others know how we feel, and it subtly changes as we age to reflect our unique life experiences.

Now, imagine if a traumatic event like a car accident or shooting fundamentally changed the appearance of your face (think Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords). That kind of trauma can be both physically and psychologically destructive to the victim, and it often requires many delicate surgeries to restore one's looks and proper brain functioning.

A growing Cleveland-based startup, OsteoSymbionics, is working to improve that process by developing a range of craniofacial implants designed to help those recovering from skull trauma. These patient-specific implants have two basic functions: protect the brain and restore one's natural head shape.

"I don’t think there is more rewarding work," says OsteoSymbionics founder Cynthia Brogan, an entrepreneur with a deep background leading tech and medical startups. "In our jobs, we all work to support a bigger cause, but to work on something so specific, that gives such immediate feedback, you feel very directly that you are making a contribution."

Brogan’s professional history has long prepared her for this work. A graduate of Case Western Reserve University, she has an MBA in marketing from the school’s Weatherhead School of Management. She began her career as a senior accountant, moving on to business development in a partnership with Case, where she was Business Director for a development and commercialization center that incubated medical tech companies.

Before starting OsteoSymbionics, Brogan ran her own interim management and consulting firm. Clients included BF Goodrich and ValveXchange, a producer of minimally invasive heart valves.

Brogen says she "danced around" entrepreneurship for years, often helping other companies grow. When this single mom’s child entered high school, she decided to start her own company.

Brogan, a former Director of Business Formations at what is now BioOhio, started OsteoSymbionics in late 2006, after working to help turn around a similar but struggling business. That business eventually failed, but the idea survived.

"After the company went out of business, some of the people who worked there said, It didn’t fail because of you. Let’s give it a shot again," Brogan explains.

So she did.

More than five years later the company has developed two products, with several more in the pipeline. Trauma victims, soldiers and cancer patients all have benefited from these cutting-edge implants.

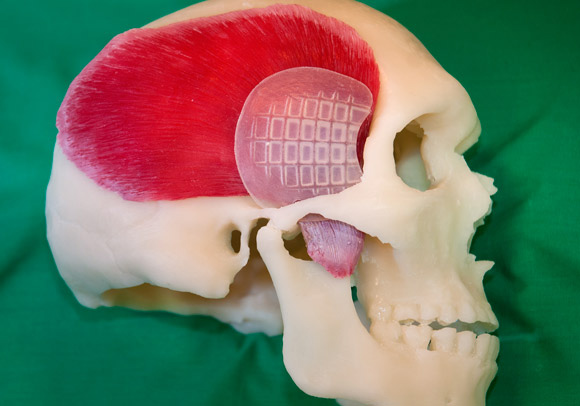

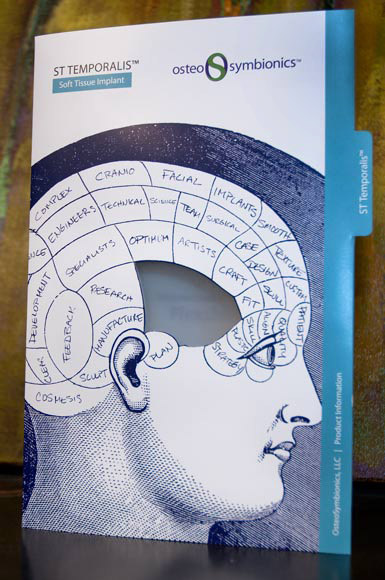

The medical startup's first product is the Clearshield craniofacial implant. It is sculpted to replace large portions of the skull that have been lost. A second smaller implant, called ST Temporalis, is designed to fill in the temple area, which can appear sunken after a trauma. That concave look is known as "temple hollowing."

These durable, permanent implants are designed to fit a patient’s skull and restore proper head shape. The custom implant is based on a patient’s CT scans and is developed in close partnership with the patient's surgeons. Made from a photoreactive plastic, the implants are designed by both computer and human -- a rarity, notes Brogan.

"We are the only company in the U.S. and possibly in the world to [design] both ways," she says. "It all starts with the CT scans that define the shape of the face and the skull. All the design work can be done with a computer model. But one of the limitations of that is that you are still designing a 3D implant with a 2D model."

That’s where the art of skull-making comes in. With more complex cases, such as an asymmetric skull or severe skull defects, where a patient doesn’t have an opposite side of the skull to mirror, the "old fashioned" sculpting model often works best.

Why does OsteoSymbionics take that extra effort in sculpting skulls?

"I’m a perfectionist. I want the best," Brogan says. "I want to feel we have done the best thing possible for that patient and for the surgeon."

The company's implants have been used by an impressive list of hospitals, including Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Cleveland Clinic, Vanderbilt University and Medical Center, and Stanford Hospital & Clinics in California.

OsteoSymbionics' implants are developed, designed and manufactured in-house. The company is located in Cleveland’s MAGNET (Manufacturing Advocacy & Growth Network) incubator, has nine employees and numerous consultants, according to Brogan.

The backgrounds of the employees are diverse, ranging from business to art to science and engineering.

"My employees use their right brains, left brains, and everything in the middle," Brogan says.

It’s the highly skilled workers and personalized service offered to surgeons that sets this company apart, explains Brogan.

"We provide the best service in the marketplace in terms of quality and the way we interact with the surgeon. We are truly partners with the surgeon and we make communication easy. When they call, they can talk to a tech person, not a sales person. We have very direct communication and are partners in planning the surgery," Brogan says.

Thanks to its track record, OsteoSymbionics is continuing to attract interest and grow. The company plans to release at least two new products in the next two years.

Photos Bob Perkoski