stories from the stove: cle's oldest restaurants have seen, been part of neighborhood change

We often don't give our old neighborhood restaurants a second thought, but they stand both as witnesses of and agents to change. As the world evolves all around them, they stand firm but flexible, preserving a delicious taste of the past while serving the ever-shifting needs of today's clientele.

From stories of fleeing war-torn homelands to street-level views of transforming neighborhoods, you'll never look at these beloved long-standing eateries the same way again.

From Hells Angels to Hipsters

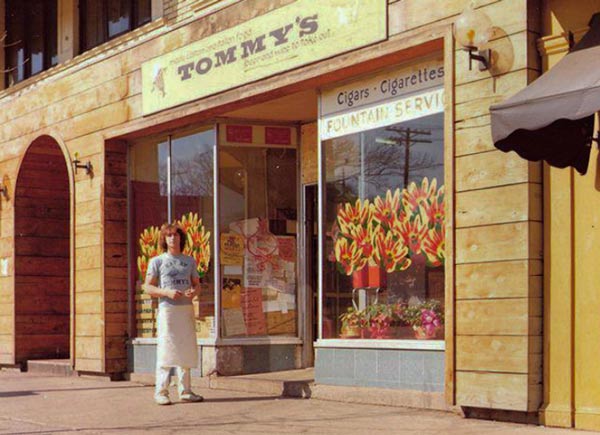

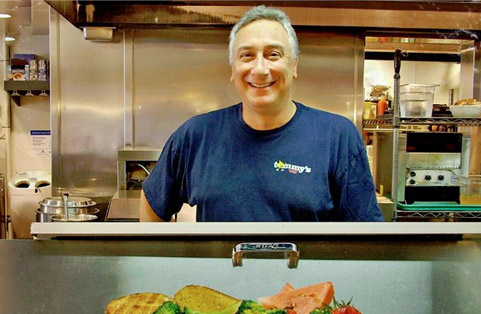

Back in the late '60s, Tommy Fello was just a teenage soda jerk -- but not just any soda jerk. The milkshakes he concocted at the Fine Arts Confectionary, at the corner of Coventry Road and Euclid Heights Boulevard, would eventually be dubbed by Rolling Stone as the "Best Milkshake East of the Mississippi," but only after the 18-year-old purchased the business in 1972 and changed the name to Tommy's (1824 Coventry Rd., Cleveland Hts).

"The neighborhood was calling it 'Tommy's' the whole time," Fello recalls. "I was working there every day and they sort of adopted me -- this young kid."

Fires and expansions moved Tommy's around over the years, but never out of Coventry Village. After all, this was home. And while Tommy's transformation from a declining drug store and soda fountain to neighborhood mainstay was primarily built on Fello's shoulders, he's quick to credit the community for his success.

"We grew up together and that’s how I became so enamored with the area and how they became so attached to Tommy's."

Fello describes the Coventry of his junior high days thusly: "There were two delicatessens, a bunch of fish and egg stores, a kosher chicken butcher shop, wholesalers, hair dressers (not like what we have today, but the kind that take care of your grandma), a couple of bars and an awful lot of ethnic people -- mostly Russian and Jewish immigrants."

Then came the hippies. Fello recalls how residents and police were leery of the peace-loving contingent. Could Coventry turn into a Cleveland-based Haight-Ashbury? To further complicate matters, the Hells Angels roamed the neighborhood.

"They were talking about running the rapid transit tracks up through here," says Fello. "There was a time when Coventry was going to be no more." The small business community decided to tackle the image problem and the Coventry Street Fair was born.

"[We wanted] to show the neighborhood and city officials: Hey, there are a lot of nice shops down here. We're family oriented. We're trying to give something to the community."

While the Fair's history has been rocky, the initial strategy succeeded and plans to turn Coventry Village into an RTA thoroughfare were derailed. The neighborhood has since evolved into a hipster haunt, although at least one Hells Angel lingers in spirit. The Beetle Omelet on Tommy's menu is named after Beetle Bailey, who was the treasurer of Northeast Ohio's "Dirty 30" Hells Angels chapter.

"He was really nice to me," recalls Fello. "He'd come in and eat every day." That was then. Bailey was shot and killed while riding his Harley through Iowa in 1975. The cold case is still open.

And so is Tommy's. While the original hippies may have since traded in their flowers for Golden Buckeye Cards, Fello cites free love as key to Tommy's longevity.

"You have to love what you're doing. You have to love the area and get love back from your customers."

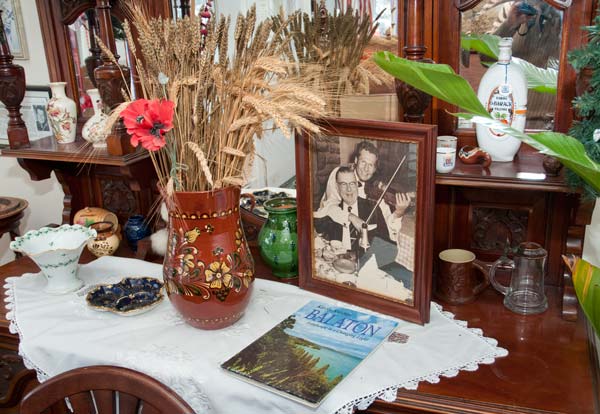

From Hungary, with Love

In 1957, Louis Olah was one of hundreds of thousands of Hungarians who fled the bloody aftermath of the Hungarian Revolution. Initially, he went to Austria where he was later joined by his mother and stepfather. Eventually, though, the family immigrated to Cleveland's Buckeye Road neighborhood, along with so many others.

"Buckeye Road was strictly a Hungarian neighborhood," recalls Olaf of what was widely regarded as an American Budapest.

"Basically," adds his niece Krisztina Ponti, "if you went to Buckeye Road in the '50s, you would think that you were in Hungary. Everybody spoke the language."

Olah's mother, Terazia, made ends meet by cleaning and doing odd jobs before she decided to put her cooking skills to use. After running a tiny carry-out restaurant and working for the legendary Gypsy Cellar, Terazia opened Balaton (13133 Shaker Sq., Cleveland) in 1964. Initially catering exclusively to Hungarians, the restaurant relied on authentic recipes from the home country -- the very same ones relied on today.

In the 1970s, the clientele began to change after the Cleveland Press ran a story about the popular Buckeye Road spot. Clevelanders at large began to belly up to steaming plates of lecso and paprikash alongside the Hungarians. By the early '90s, Krisztina, a formally trained chef, and her sister had immigrated to the States to work at the family restaurant.

Balaton's reputation continued to spread and soon hit the national stage, with write-ups in Bon Appetit and Gourmet. All the while, the neighborhood around them was changing. Second and third generation Hungarians were moving to the suburbs, and the ethnic businesses followed.

"We were almost the last [Hungarian business] to move away from Buckeye," says Olah. But where to go from there?

"We wanted to find a location that was not too far from the original location and had Old World charm," says Krisztina. "Shaker Square offers you that. It's very ethnic and very unique."

"It's very multi-national," adds Olah.

The restaurant opened at its current location on Shaker Square in 1997. Unlike 50 years ago, today's customer base is as varied as the surrounding neighborhood, though plenty of lifelong customers still drop in for stuffed cabbages and goulash. These days, they bring the kids and grandkids.

"It's still remains a family gathering place," says Krisztina, "especially during the holidays."

But does anyone still speak the native tongue?

"We still speak Hungarian in the kitchen," says Krisztina, "especially when we are angry."

Catering to a Vertical Neighborhood

When it comes to longevity, Pier W (12700 Lake Ave., Lakewood), adjacent to the swanky Winton Place, has serious street cred.

Having outlived legendary Gold Coast venues such as The Marius (housed in the once opulent Lake Shore Hotel), The Blue Fox (a notorious mafia haunt) and The Silver Quill, (last owned by the now-defunct Swingos empire), Pier W will celebrate 50 years of white tablecloth dining next year. It's also all that remains of the Stouffer's restaurant legacy in Cleveland, which included landmarks such as Top of the Town and John Q's.

"The other day we had a lady come in for her 100th birthday," says GM Mark Kawada, adding that she was different from the other centenarians he's seen celebrate at the lakefront eatery during his brief tenure. This young lady also had celebrated her 70th, 80th and 90th birthdays here. Another recent customer not only got married at Pier W, but also has enjoyed all 45 anniversary dinners here since.

"There's a history of memories here," says Kawada, "and I think that's what makes it great."

He credits the staying power to the spectacular views, attention to detail and maintaining that delicate balance between old and new. The vintage bell diver suit has welcomed diners for decades, while the recently updated interior is contemporary, with gleaming glass and blue accent lighting. And while the bouillabaisse recipe hasn't changed in 49 years, management's attitude toward its ingredients has.

"No one cared where fish came from 50 years ago," says Kawada. "Now all of our seafood is 100-percent sustainable."

The tony enclaves of the Gold Coast are notably different from more traditional neighborhoods, but the nearby customer base needs nurturing all the same. To that end, Kawada offers special discounts to residents of the nearby Winton Place, Carlyle and Meridian. Catering to private suites? No problem. And for Winton Place denizens, the interior walkway to the posh bar makes happy hour all the happier.

Despite the restaurant's longevity and reputation, Kawada says that a shocking number of Clevelanders have never even heard of Pier W.

"If you talk to people on the East Side, they have no idea who we are or where we are," he says, adding that the anomaly represents fresh opportunity. "It's exciting; I have a whole different market to captivate. All I need to do is get them in here."

"Where we were and where we're heading."

In 1975, Lebanon was thrown into a devastating civil war. By 1980, Joe and Sally Maalouf decided it was time to get their three young children out of the war-ravaged country.

"It was just a fearful place to be," says son Ghassan Maalouf of the Lebanon he left as a young child.

The Maalouf's immigrated to the United States, namely Cleveland, where they had a network of Lebanese family, friends and churches to rely upon.

Sally worked at three restaurants, including the unassuming Nate's Deli (1923 West 25th St., Cleveland), where she cooked alongside owner Nate, who was also Lebanese. When he decided it was time to sell, Sally persuaded Joe, a lifelong cabinetmaker, to take the plunge. He agreed and the venture turned into a family affair.

Ghassan, now the general manager of Nate's, was just nine years old when he started working at the restaurant in the mid-1980s.

"My dad wouldn't let me walk out on the street by myself," he recalls of Ohio City at the time. "There were drug dealers and drunks all over the place. It was quite a mess."

But the cornerstones of the neighborhood -- Lutheran Hospital, West Side Market, St. Ignatius -- were unwavering, and they bolstered small businesses such as Nate's. As the years passed, the Maaloufs watched Ohio City transform from a gritty urban pocket to one of Cleveland's most popular destinations.

"It's something that's been self-sustaining over the years, but the neighborhood is just getting the credit for it now," says Ghassan. "It doesn't seem like it's the next fad. It's somewhat of a renaissance."

He succinctly sums up his neighborhood's Old World-meets-New charm.

"Ohio City is where we were and where we're heading all in one shot, right here between a few street lights. It's pretty incredible."

Note for the grammar police: the Hells Angels do not use a possessive apostrophe in their name, so neither did we.

Photos Bob Perkoski