the talent dividend: how more college grads can add to cleveland's bottom line

Cha-ching!

What if Cleveland could attract a company that generated revenues of a billion dollars or more? Think along the lines of a megabank like PNC or a sizzler of a tech company like Facebook.

Well, what if we told you that Northeast Ohio could pull in even bigger numbers -- something on the order of $2.8 billion -- without landing a single new company? We can, simply by increasing the number of college graduates in our region by a single percentage point.

"The best way to measure the economic success of a city is per capita income, and the simple most direct connection of per capita income is college attainment," says Lee Fisher, president of CEOs for Cities, a civic lab and network of urban leaders across the country.

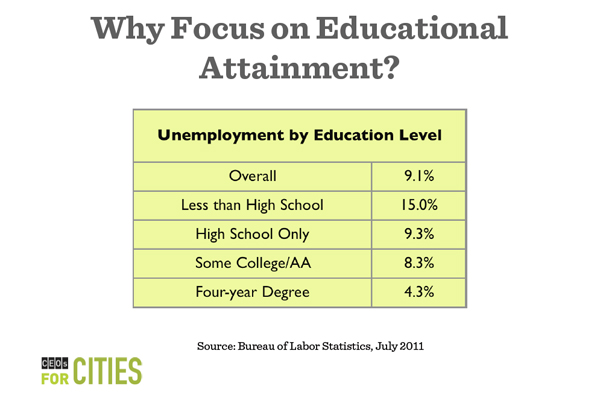

The Talent Dividend, an initiative out of CEOs for Cities, calculates that a one-percent increase in a city's college attainment level translates into a per capita increase of $763. In Northeast Ohio, that adds up to a whopping $2.8 billion of new income per year -- all by bumping up the number of four-year college degrees. That money, of course, would percolate its way through the entire local economy.

The more educated a city, the more robust its economy, reports Joe Cortright, author of the study. The percentage of college graduates in a city's population accounts for 58 percent of a city's economic success, as measured by per capita income. Simply stated: The most successful cities have the highest number of college grads.

If that's not incentive enough to boost college attainment, here's another. Thanks to support from the Kresge Foundation, Lumina Foundation and DeVry, CEOs for Cities is offering a $1 million Talent Dividend prize to the city that produces the biggest per capita increase in college-degree earners over a three-year period. The prize will be used to launch a national promotional campaign focused on talent development.

And while 57 cities across the country -- including our own -- are competing in the contest launched in May, that million-dollar carrot merely is an incentive and rallying cry. The point, and the larger prize, is for each city to raises its college graduation rate, and thus increase per capita income.

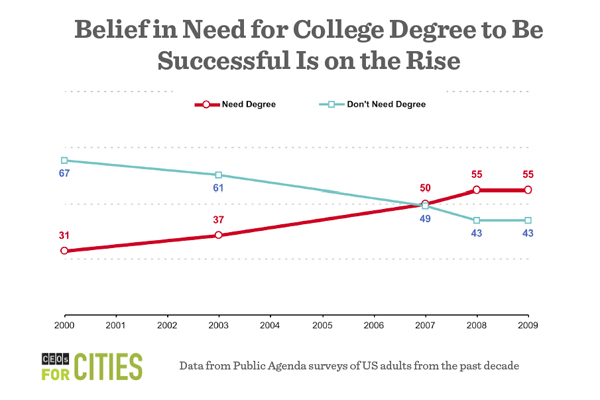

But there's even more at stake for society, as New York Times columnist David Brooks recently argued. In writing about the polarization of our country, Brooks said, "the crucial inequality is not between the top one percent and the bottom 99 percent. It's between those with a college degree and those without.

"Over the past several decades," he writes, "the economic benefits of education have steadily risen. In 1979, the average college graduate made 38 percent more than the average high school graduate, according to the Fed chairman, Ben Bernanke. Now, the average college graduate makes more than 75 percent more."

Increasing college attainment by one percentage point in each of the 51 largest metropolitan areas would be associated with an annual increase in personal income of $124 billion for the U.S, according to the Talent Dividend research.

NOCHE is on the job

In Northeast Ohio, 30.2 percent of adults aged 18 and older possess an Associate's, Bachelor's, or post-graduate degree. This compares unfavorably with the national average of 37.3 percent. That figure not only is regrettable, it's surprising given the quantity and quality of higher learning options in our region.

"If you live in Northeast Ohio, you have access to almost every college option available," says Shawn M. Brown, Associate Director of Northeast Ohio Council on Higher Education (NOCHE). He should know; his organization is the one leading the charge locally to up our region's college attainment level.

From open-admission two-year universities to some of the most elite private liberal arts colleges, Northeast Ohio is blessed with a wide range of higher learning options. Spread across our region is a diverse network of two-year community colleges, public state universities, and private colleges.

"The future economy in Northeast Ohio is going to be dependent upon having an educated workforce," Brown explains.

The goal of NOCHE and the Talent Dividend initiative is to raise the percentage of local degree holders from 30.2 to 32.3 by 2014. In real numbers that means adding 60,000 pieces of parchment to the walls of Northeast Ohio homes. To get there, NOCHE will attack on multiple fronts.

By improving the college readiness of both high school and adult students before they step foot in their first classroom. By increasing student-retention figures so that more people who start college actually finish college. By allowing high school students to earn college credit by taking certain classes – a concept called "dual enrollment." By giving adult students college credit for real-world experience gained in the workplace or military. And by focusing on adults with some college experience but no degree -- what Brown calls "low-hanging fruit."

"There are 583,000 people in Northeast Ohio -- more than a half million -- with some college credit," he explains. "These are people we know are college material because they have already been admitted to a college." Not only do these older students have college credits to transfer, they are more mature, motivated and know first-hand the importance of a degree in today's world.

On December 16, NOCHE will host the annual Talent Dividend Summit, where it will describe the progress that has been made thus far. Dr. E. Gordon Gee, president of The Ohio State University, will be the keynote speaker.

The Need for Cultural Shifts

While citywide initiatives like those of NOCHE and the Talent Dividend could be effective in getting more people through college, it would help for colleges to be more flexible. In an article in Forbes last year, Carol Coletta, former head of CEOs for Cities, argues that since almost three-quarters of college students today are adults in the workforce, "colleges must adapt their schedules, their product distribution channels and their methods to serve these students and make degree completion more likely."

Employers, too, have a role to play, she notes, by offering flextime and place to workers trying to complete their degrees. And universities, especially those that are publicly funded, must make it easier to transfer credits between institutions.

In the end, "education gains are a product of a shift in entire skill distribution - not just moving a certain number of people from no degree to college graduation," says Cortright. Any gain is good and while three years is a short time, it's a good start.

Prize or no prize, it's hard to lose in this contest.

Tracy Certo is publisher and editor of Pop City in Pittsburgh, a sister publication of Fresh Water.

Photographs of University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University copyright Brian Cohen