the freelance life: how some locals are cobbling together the careers of their dreams

When I was downsized in 2009, I was terrified. I had a two-week-old daughter at home and no Plan B. But I soon discovered that plenty of people were willing to hire me for my writing skills. Almost none of them wanted to hire me full-time, however, and I wasn’t interested in the non-writing jobs that were out there. Pretty soon, I was piecing things together.

Welcome to the "gigging life," a livelihood consisting of hopping from one job to the next like an Eskimo on an ice floe, cobbling together a family budget from small checks that never arrive on time, learning to do your own taxes (while deducting everything under the sun), and -- here's the good part -- working from home with the shortest commute imaginable.

Since making the leap to writing full-time, I've written for publications as diverse as Modern Farmer, Agence France Press and Rails to Trails, interviewed everyone from college presidents to cupcake shop proprieters, and found an audience for my work. I've never been more fulfilled. Although I sometimes miss the benefits and regular hours of traditional employment, I'm doing what I love.

And I'm not alone: There are at least 15 million self-employed Americans, according to 2012 numbers from the U.S. Department of Labor. Emergent Research, a California firm that conducts a national survey of independent workers, says that number could balloon to 24 million by 2018.

In the wake of the recession, more and more people are working multiple jobs because they have to and -- if they’re fortunate like me -- because it's a way to pursue one's passion. In our virtual, fast-changing world, many employers also find it easier to hire people on a project basis.

I recently caught up with several Cleveland-area freelancers in their 20s and 30s to find out what they’re doing, how they’re doing it and whether Cleveland, with its affordable cost of living, is a good place to hang out one's own shingle.

Max Stern, 24, musician and graphic designer

Cleveland Heights native Max Stern started college in the grimmest days of the recession, an experience he describes as “terrifying,” but also one that galvanized his career.

“I had no clue what I’d do after college -- I thought I’d work at an Apple shop or a guitar store,” says Stern, who lives in Tremont and plays in the bands Signals Midwest and Meridian. “But the idea of working for a big company was not that appealing. It’s nice to be able to carve out my own path.”

Getting here was tricky, though. Stern has worked as a landscaper, sign maker, babysitter and house painter, to name but a few of his gigs. After graduating from Cleveland State University in 2012 with a degree in advertising, Stern moved home where he had a Lena Dunham-esque freak out: What am I doing with my life? he brooded.

To get perspective on “the looming possibilities of adulthood,” he traveled to Israel and lived on a kibbutz as part of a program for American Jews to learn their heritage. “I got lost in the desert for a month. It was a pretty good time.”

When he came home, he found an email in his inbox asking him to freelance on some graphic design projects, and he slowly built up a roster of clients, including a private college near Boston and a big record label in L.A. He's noticed that he's not alone in his situation as more and more of his peers also have found jobs that allow them to continue pursuing creative lifestyles, a way of life he cherishes.

“I don’t have to answer to anyone if I don’t want to. I can do it on my own terms.”

Ashley Shaw, 28, local food advocate

With just one in five of her friends finding "real jobs" after college, Berea native Ashley Shaw was too scared to turn down her first big job offer. But after two years of being a mid-level publicist in L.A. -- and hating the hectic, traffic-clogged lifestyle that accompanied it -- she wanted out.

“I didn’t think I should love my job and nothing else about my life,” says Shaw.

She came back to Cleveland to pursue a Master’s degree in Urban Planning from Cleveland State University, but after graduating she couldn’t find a full-time job. Instead, she took a part-time job running the Downtown Farmers Market, which moves during the winter months to the 5th Street Arcades. She loves her work building the local food scene.

“There are more businesses now because they have more outlets to sell their products,” she says.

She also juggles three other part-time jobs: she is Special Projects Coordinator for the Historic Warehouse District, she works on weekends for Fresh Fork Market (“grocery money” and a steady supply of fresh food), and she does freelance marketing and PR for her former employer.

The good part? Working from home on Mondays and having lunch at the West Side Market. The bad part? Paying her taxes and surviving without healthcare for five years.

“I’ve been able to enjoy these things because I don’t spend a lot on my living costs,” she says. “In L.A., I worked 10- to 12-hour days and still couldn’t make a living.”

Lynn Rodemann, 33, urban chicken farmer

Lynn Rodemann is a homeschooling mom and barista with a five-year plan. She leased an acre of land in the almost-wilderness around E. 82nd Street off Kinsman, where she's created the largest urban chicken farm in Cleveland since… well, probably ever.

“I had an epiphany one day a few years ago,” recalls Rodemann, who used to be a vegetarian. “Some [chicken-farming] friends and I went into the woods to slaughter chickens. It was such an intimate connection doing this with my best friends.”

Although Rodemann jokes she had a "Portlandia moment" -- “This is Collin and he’ll be your meal today. He last ate a meal of wild foraged hazelnuts…," she jokes -- it’s really more than that. “That was the closest I’ll come to church or a spiritual experience,” she says.

Food is the mortar that holds Cleveland’s disparate enclaves together. “What makes a city communal and transcends lines of race and class? Food does,” she posits.

Aided by a $5,000 grant from the city, Rodemann purchased moveable chicken coops, a feather plucker and other equipment she'll need to process 100-plus chickens before the holidays. In the spring, she'll ramp up production even more, adding 80 layer hens for eggs and processing 100 meat birds every five to eight weeks. Her typical day involves getting up at 6 a.m., driving out to Kinsman to feed her chickens, homeschooling her two sons all day, and pouring lattes all night.

“It’s make-it-or-break-it,” says the entrepreneur, who dubs her startup Cleveland Urban Egg. She enrolled her family in public assistance to get through lean times, a fact she’s proud of because she defies the stereotypes, but she aims to become a self-sufficient farmer.

“I feel fulfilled for the first time,” she says. “I know I’m not wasting a minute of my time. I’m going to do it -- I’m the most determined person I know.”

Tara Pringle Jefferson, 27, mommy blogger

Tara Pringle Jefferson got the idea for her blog while sitting in the doctor’s office during her second pregnancy, leafing through glossy magazines.

“I picked up a parenting magazine and it had a $600 stroller and gadgets that were a 'must-buy,'” says Jefferson, who became pregnant with her first child as a student at Kent State University and navigated young motherhood on her own. “I looked at the pictures -- nobody reflected the way my family looked.”

She worked several years in PR and marketing for the Cleveland Foundation, but left in 2010. Today, she has a marketing and social media consultancy and has developed a mommy blog, The Young Mommy Life, aimed at moms under 25.

“I created a website because of the lack of diversity I found in parenting media,” says Jefferson, whose blog attracts 20,000 readers per month and has earned advertising through the BlogHer network.

The hardest part of freelancing is setting limits and all the paperwork. “You’re the accounting department, marketing department and mailroom,” she says. “A lot of people that branch out on their own don’t realize: It’s not just about following your passion.”

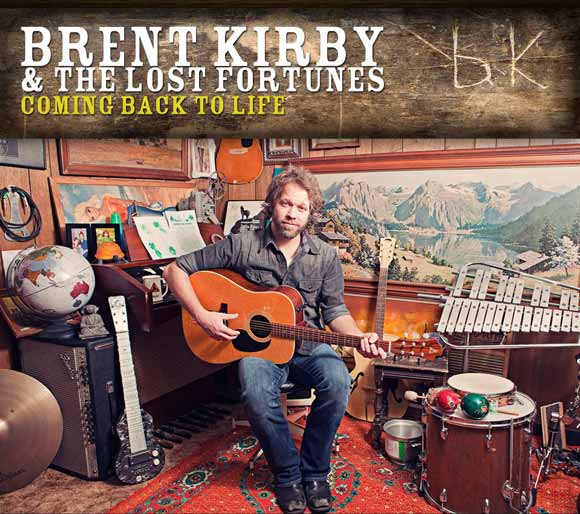

Brent Kirby, musician

Brent Kirby has won Best Singer, Best Musician and Best Rock Band from Scene’s Music Awards. He makes it work by playing in five different bands, including Hey Mavis, Brent Kirby and the Lost Fortunes and the Gram Parsons cover band The New Soft Shoe.

“I started the band as a drunken dare,” he says of the Parsons outfit, which plays once a month at the Happy Dog. “‘Who wants to play Gram Parsons tunes at the Happy Dog?’”

Although some cover bands are lucrative, Kirby started The New Soft Shoe out of passion for the music. “If I wanted to make money, I shouldn’t have picked Gram Parsons. But now we’ve met his daughter and worked with the Gram Parsons Foundation.”

Kirby does make money, though; a rare full-time living as a musician, actually. He’s put it together by being a savvy businessman, diversifying his musical offerings and connecting with audiences. “One of my favorite parts is when people quote song lyrics. They come up and say, ‘What do you mean by this?’ Then I know they’re listening to the words.”

Kirby, who has been playing in bars since he was 13 and says it’s “in his blood,” worked for Sam Ash Music and Verizon Wireless in the past. “I made more money than I’ve ever made in my life, but it was high-pressure sales. I hated every minute of it.”

Today, he hustles to find gigs in the local music scene, but finds it all fulfilling. “Cleveland is experiencing a renaissance. I’m constantly hearing of new places that are adding music.”

Lynn Rodemann photos Bob Perkoski