all aboard: urban transit stations redeveloped as neighborhood amenities

Even as the economy recovers, Americans are driving less. In urban areas across the country, people instead are choosing to walk, bike or take public transit.

When we have a long way to go, there's strong evidence that the Great American Roadtrip also is on the wane. Amtrak has set a new ridership record in 10 of the past 11 years, with fiscal year 2013 being its best ever with 31.6 million passengers riding.

With all that demand comes congestion and backups at major rail hubs, but smart cities are anticipating and adapting so that the train station of the future is full but not crowded, busy but not packed. And rather than being a place that commuters hurry through, the renovated train stations of tomorrow will be neighborhood amenities.

The $7 Billion Question in Washington D.C.

One of D.C.'s most-visited places and one of the country's busiest train stations is due for an upgrade. Union Station is packed to the gills with people -- almost 50,000 per day -- who funnel through narrow platforms and very few entrances and exits. A single MARC train can carry 1,050 people, roughly the equivalent of three jumbo jets.

An ambitious Master Plan for the station envisions widening the train platforms to move people more efficiently through them, doubling the amount of parking, more than doubling the amount of space for passengers waiting on the concourse and, above the tracks, adding three million square feet of office, residential, hotel and retail space, in a project known as Burnham Place.

"We're knitting a hole in the urban fabric," says Corinne Scheiffer, outreach and communications head for the Union Station Redevelopment Corporation, which manages Union Station.

David Tuchmann, vice president of development for Akridge, which will be developing Burnham Place, adds that while increasing capacity is an important goal, it's not the only goal. "We've succeeded if you say, 'I live right on top of Union Station,' and people say, 'Wow.'" The station, in other words, has to be an amenity in itself, not just a machine for moving people from point A to point B.

The new Union Station and surrounding area will get seven acres of parks and plazas (including a two-acre elevated greenway that will connect to the Metropolitan Branch Trail), a "substantial" amount of retail, and the train hall, a sweeping glass structure, will be viewable from nearly every proposed building in Burnham Place. The playgrounds, restaurants and shops in Burnham Place will be used by commuters and tourists, not just the people who live and work there. In that way the train station becomes part of the neighborhood and the neighborhood becomes part of the train station.

The design also calls for adding at least eight additional entrances to the station (currently there are only three, all clustered on the south and west sides) so that commuters coming from the north don't have to walk as far and neighbors can pass through the station rather than having to walk around it.

"It might be that people who live in this area will make this their everyday walk," Tuchmann says. "They can walk down the greenway, enter the station, get a yogurt or smoothie, and walk back. They're not a tourist or commuter." They're not even buying a train ticket. But that's okay.

Minor aspects of the first phase of the Master Plan are underway, but the overall plan will take 15 to 20 years and cost $7 billion dollars, paid for from a variety of sources still in negotiations. If completed at this cost, it would be one of the most expensive megaprojects in U.S. history. But, says Tuchmann, "The only solution is generational thinking. We're trying for the bigger moves, to make sure people look back 30 years from now and say, 'Wow.'"

It used to be that the train station was intended to be set off from city life. Trains were loud and smelly, and you only needed to get on one if you were traveling a long distance. Now, says Brian Harner, master plan coordinator for Amtrak, "We've learned about the power of transportation networks to create cities. The value of that goes way beyond the number of people you move."

The Porch in Philly

Philadelphia's main train station on 30th Street, on the banks of the Schuylkill River, is the nation's third busiest, with over four million passengers boarding or disembarking a train. Add in the local SEPTA trains and New Jersey Transit and that figure rises to seven million passengers per year. Thousands of people experience Philly for the first time as they exit the train station.

But until a few years ago, that initial view was of a parking lot. "It was my first impression of Philadelphia," says Prema Gupta, director of planning for the nonprofit University City District, an organization similar to a BID dedicated to revitalizing the neighborhood surrounding the Amtrak station and six nearby universities. "I got off the train, and you get out of the station and there's this magnificent view of the skyline, but then you're in this concrete jungle and surrounded by automobiles."

When the city decided to turn the parallel parking in front of the station into a pedestrian sidewalk, Gupta and UCD argued that it should not be just a pedestrian thruway, but a place where "people close their eyes and put up their feet, [a place where] we can civilize five minutes and encourage people to linger." In 2011, The Porch was born. UCD installed plants, tables and chairs and set up space for events like a farmer's market, outdoor concerts and fitness classes, even mini golf.

During its first summer, almost 25,000 people visited the space -- not just passed through, something Gupta can say with certainty because UCD surveyed the space every hour and every day to determine how The Porch was being used. UCD wanted to "demonstrate that there's a huge amount of demand to justify future investments."

With 11 acres of nearby surface parking under study by Amtrak, Drexel University and Brandywine Realty Trust for redevelopment, and with 30th Street Station itself scheduled for a future renovation, those future investments in a pedestrian-friendly, relaxing green space seem like a no-brainer.

Raising up Lowertown in St. Paul

If you were to take Amtrak into the Twin Cities today, you'd end up in Midway Station, located on the aptly named Transfer Road. About halfway between the downtowns of Minneapolis and St. Paul, the 1970s-era building is about as attractive as 1970s-era buildings typically are, which is to say not very much.

But if you ride Amtrak into the Twin Cities in a few months, you'd coast into downtown St. Paul's newly restored Union Depot, that city's original train station and the only historic train station remaining in the Twin Cities.

More than 10 years ago, the Ramsey County Rail Authority determined that bringing rail back to downtown would be a positive for the city of St. Paul. After Midway Station opened, the historic Union Depot in the neighborhood of Lowertown was used as storage for the post office. Finally, after a 10-year and $250-million renovation, Union Depot reopened to the public in 2012. It's currently a bus hub, but Amtrak is expected to move back before the end of the first quarter of this year, and a light rail line will open this summer. "Amtrak was really excited when the board undertook this initiative to... bring back Union Depot," says Tim Mayasich, director of the RCRA. "It's a much better experience for their passengers to be here."

The Twin Cities Amtrak station saw over 116,000 boardings and alightings in the last year, and the one route that runs through the Twin Cities is "busting at the seams," Mayasich says, because it runs west through North Dakota where the "fracking" boom is attracting thousands of workers.

Redeveloping the central train station has had predictable effects on the nearby neighborhood. Lowertown is now the fastest growing part of St. Paul, full of artists, restaurants and, soon, the local minor league baseball stadium.

Midway Station served its purpose, says RCRA real estate manager Jean Krueger, "but it's kind of nowhere. Whereas Union Depot is going to be one of those things where everyone is going to know where it is."

Booming Ridership, Expanding Service in Cleveland

All Aboard Ohio (AAO), a rail advocacy group, is pushing state and regional leaders to look past the turnpike and start paying more attention to its deteriorating Amtrak stations. In Cleveland alone, ridership has increased 38 percent over the past five years, and that's despite the fact that just four trains pass through town on any given day -- and all of those are in the dead of the night.

It’s not surprising that demand is high considering that the cost of driving has shot up 71 percent since 2000, according to the IRS.

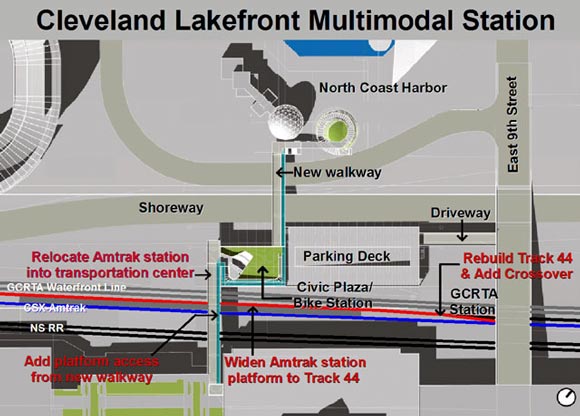

If AAO Executive Director Ken Prendergast gets his way, an ambitious new Lakefront Multimodal Station that would accommodate all intercity transportation services will coincide with rehabilitation efforts for the Amtrak station.

“As rail and transit ridership continues to rise and per-capita driving declines, creating such a multi-modal transportation center will create efficiencies and a foundation for more transportation services and future growth for the region," says Prendergast.

AAO estimates that there are 480,000 intercity boardings per year in Cleveland via service providers such as Greyhound, Megabus and Amtrak. Add to the mix 310,000 regional transit riders within a 60-mile radius and you end up with a figure that's roughly the equivalent of the total number of passengers boarding aircraft at Akron-Canton Airport.

Cleveland’s own RTA is experiencing a boom in ridership, with a two-percent climb overall (or about one million more rides) in 2013, a five-percent jump on the HealthLine, and a three-percent spike on the Red Line. In short, RTA had its highest ridership total in more than 25 years.

To best capitalize on the growing transit trend, RTA is studying service extensions eastward on both the Red Line and HealthLine. Valerie Shea, RTA Planning Team Leader, says the service provider currently is screening four plans that consider the costs and demand for extending the Red Line eastward past Windermere, or implementing “street running alternatives” via bus rapid transit (think HealthLine) or a rail car called “Rapid +.” Clevelanders can see the routes under consideration online.

Meanwhile, a revamped Cedar-University station is on schedule for completion by the end of this year with excess bus-only pavement converted to a pedestrian and cyclist path, which complement the station's updated, modern design. The Cleveland Foundation donated $250,000 to develop a "green" concept for the station, including new roofs and an enclosed vestibule that will allow riders to wait comfortably indoors.

Construction also recently began on the new Little Italy-University Circle station. RTA is eliminating the Euclid/E. 120th station and opening a new one in Little Italy, at Mayfield and E. 119th. That station -- a hop, skip and jump from Uptown in University Circle -- will open by 2016.