school's out forever: the challenge and opportunity of surplus schools

In the early 1960s, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District struggled with overcrowding as the population in Cleveland exploded. But since the 1970s, administrators have faced a very different problem: the district’s enrollment has declined by more than 100,000 students.

As a result, the district has closed and demolished many school buildings. Others have sat vacant for years.

Cleveland, which has lost more than half a million residents since its population peak in the 1950s, is one of many U.S. cities struggling to manage an oversupply of school buildings.

“We’re left with the legacy of schools that were built when Cleveland was the sixth largest city in the country,” says Patrick Zohn, the district’s chief operating officer.

Since 2005 alone, CMSD has closed 35 schools and demolished 14 as enrollment plummeted by more than 26,000 students, with about 39,200 students enrolled today. Enrollment projections from the Ohio School Facilities Commission estimate that by the 2018-2019 school year, the student population will fall to 32,443, and by 2023-2024, enrollment will be about 30,526 students.

In February 2013, The Pew Charitable Trusts released a report examining 12 cities with surplus schools, including Cleveland, Detroit and Philadelphia, and what happens to buildings once they close. Since 2005, the 12 districts had sold, leased or reused 267 properties, and had 301 empty buildings on the market. When the report was conducted at the end of 2012, Cleveland had repurposed, leased or sold 25, and 26 buildings were on the market.

Gary Sautter, Deputy Chief of Capital Projects for CMSD, says the district works closely with the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission to determine the viability of renovating versus replacing a school.

When a building is closed and there are no plans to reopen it, the district goes through the necessary steps to determine if the building should be maintained or torn down, he says.

“We work with [the OFCC], and it’s a balanced approach,” Sautter says. “We have when necessary removed buildings that really have no use to us or anybody else that are either aged or need significant repairs.”

Yet the process is a lengthy one, and surplus schools can sit vacant for years as the district figures out what to do with them. In the meantime, they’re vulnerable to thieves and the elements. Kathleen Crowther, Executive Director and President of the Cleveland Restoration Society, has tried to protect historic schools from demolition, but said she has had a “limited impact.”

Yet the process is a lengthy one, and surplus schools can sit vacant for years as the district figures out what to do with them. In the meantime, they’re vulnerable to thieves and the elements. Kathleen Crowther, Executive Director and President of the Cleveland Restoration Society, has tried to protect historic schools from demolition, but said she has had a “limited impact.”

“The schools that were built in Cleveland were built as really monuments to education. They were built of very fine materials that would last through the centuries … And they were embellished in the architectural style of the day, with lots of symbolism of the importance of education and the idea of advancement through study,” Crowther says. “Even if the school district did not want to fix up the building, I think it would be better for them to convert that building for a new use, [such as] housing, which is a wonderful adaptive use of school buildings.”

An old problem

Surplus schools in cities are not a new phenomenon.

Thomas Matheny, vice president and CFO of architecture and design firm Schooley Caldwell Associates in Columbus, co-authored a report, “A Guide for the Adaptive Use of Surplus Schools,” published in 1981.

“It’s a problem that communities have been dealing with for decades now, but somehow districts are still unprepared,” said Matheny, who specializes in adaptive reuse and historic preservation.

Often schools “mothball” structures as they wait for the market to improve or enrollment to change.

“They are investments that the communities made, and there is this fear that the demographics are going to turn around and all of a sudden they’ll need those buildings,” he said.

Of the 35 buildings closed in 2005, eight have been restored for other CMSD purposes, such as swing space during construction projects.

And selling property isn’t easy, Zohn said, in part because the district has to follow specific procedures. Government entities get first dibs if they want to pursue a land swap. Then, the district must give community schools a 60-day window to decide if they would like to purchase buildings. After that process is complete, buildings go through a public auction phase, but the Board of Education has to approve the offer from the highest bidder. If the offer is not approved, then the option of selling the building is considered. There are no buildings actively for sale at this time.

Developers that specialize in finding adaptive reuses have helped offset the number of vacancies in some cities, including Detroit.

“The process [of selling or repurposing schools] takes considerable effort on the part of districts,” according to the Pew report. “Districts must pay for maintenance, security and insurance while they search for new occupants … Finding new uses entails dealing with market challenges, working within state and local policy constraints, and balancing sometimes conflicting goals about a property’s best use.”

As buildings are in limbo, they continue to deteriorate, reducing their value and investor interest. Boarding up buildings costs anywhere from $50,000 to $100,000, Sautter said.

“When a building becomes vacant, it’s symbolic because now there is an empty building that’s in the center of the community,” Matheny said. “They deteriorate, which is not good for the surrounding community … it changes the whole dynamic of the community, and not for the better."

One example is the historic section of Watterson-Lake Elementary School on W. 74th Street and Detroit. The original school, designed by early Cleveland School architect Frank S. Barnum, was built in 1906. Since the 1980s, that portion has been unused and "appears as if it's crumbling; there are literally pieces falling off of the building,” says Jenny Spencer, managing director of the Detroit Shoreway Community Development Organization. “The community has watched this building fall apart.”

One example is the historic section of Watterson-Lake Elementary School on W. 74th Street and Detroit. The original school, designed by early Cleveland School architect Frank S. Barnum, was built in 1906. Since the 1980s, that portion has been unused and "appears as if it's crumbling; there are literally pieces falling off of the building,” says Jenny Spencer, managing director of the Detroit Shoreway Community Development Organization. “The community has watched this building fall apart.”

The building was designated by the Cleveland Landmarks Commission about 10 years ago, and Spencer says numerous studies were conducted to determine its condition.

“Neighbors had immediate concerns about the building’s safety and structural integrity, and pulled together with DSCDO and Councilman Matt Zone to ensure that CMSD would secure the building,” she says. “While many neighbors would love to see the historic 1906 building preserved, others believe it would be better to demolish the building to make way for a new construction development site, potentially housing.”

Watterson-Lake is slated to eventually close under the district’s current Facilities Master Plan, and the recommendation is to sell the site for redevelopment. Spencer says that due to the challenging conditions of the Watterson-Lake site, a potential developer would need to come forward with a viable rehabilitation plan and extensive experience with historic tax credits.

Renovating, rebuilding and razing

Despite the declining enrollments in Cleveland, the district has razed and rebuilt many school buildings with the help of state money from the Ohio School Facilities Commission, established in 1997 to manage K-12 construction projects and recently merged with the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission, which now approves projects. Sautter says the OFCC pays for 68 percent of the cost of state-approved demolitions, which run $600,000 to $2 million and convert sites into green spaces.

The state funding available to districts is the most significant change Matheny says he’s seen since he wrote the surplus schools study.

“As a result, there are a significant number of new buildings being built … to replace existing buildings that are seen as outmoded and unable to be modified to meet current standards,” Matheny said. “We’d much rather see school districts take their historic schools, which are in most cases in the center of the neighborhood, and renovate them to meet the contemporary standards, and that is absolutely possible.”

The latest Facilities Master Plan, the CMSD’s roadmap for school buildings through 2019, aims to “minimize the number of school closings in order to give the district flexibility in accommodating growth or shifting enrollment patterns,” according to the board-approved plan. Thirty four schools have been rebuilt and seven renovated with Issue 14 money since 2001. The latest plan, made possible by a $200 million bond approved by voters in November and more than $2 for every $1 the district spends from state, outlines recommendations for 49 additional buildings.

Those recommendations, which are a result of community meetings and work with the OFCC since 2012, call for replacing 20 to 22 structures on the existing school site or a nearby new site, and refurbishing 20 to 23 others. A handful of schools are slated to be closed. Some have undetermined futures, recommendations call for others to be sold and those in disrepair to be demolished.

Zohn said they are currently working on segment agreements with the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission, which they will likely present to the school board for approval in February or March.

Nine schools (not including Watterson-Lake) are vacant and “past their useful life,” Zohn says, but are still in limbo. Audubon Middle School, Empire Junior High School, Robert Fulton Elementary School, Mt. Auburn Elementary School and Willson Middle School, built between 1903 and 1929, are landmarked by the Cleveland Landmarks Commission. “Until the landmark designation is removed, it makes it difficult for us to move forward with demolition,” Zohn said.

The Cleveland Landmarks Commission must review a landmarked building’s architectural and historical significance, condition issues, architectural integrity and other factors before it approves a demolition. Four other empty schools – built in 1914, 1917, 1924 and 1940 – are not landmarked. There are at least two dozen buildings in the district that have official landmark status.

Historic preservation is important but not ‘first priority,’ state says

Rick Savors, spokesman for the Ohio Facilities Construction Commission, says 40 to 45 percent of the projects the OFCC oversees are renovations of existing structures, but that rehabbing older buildings isn’t always the best option.

“The way we provide educational programming in Ohio has changed dramatically over the past 40 to 50 years. What was at one time a very fine building to provide education is now extremely outdated,” Savors says, explaining that teachers need bigger, more flexible classrooms to house small group work. “We build 900-square-foot classrooms, but some of these buildings have 600 square-foot rooms.

“You may have a building that’s structurally sound, but it would cost so much to reconfigure.”

The OFCC has also encountered unexpected costs when renovating historic buildings, Savors says. As layers of buildings are peeled away, problems are revealed. Some structures can’t be saved.

The OFCC has also encountered unexpected costs when renovating historic buildings, Savors says. As layers of buildings are peeled away, problems are revealed. Some structures can’t be saved.

Matheny said this is an “oft-stated” argument against historic preservation.

“Existing buildings require a different approach, but you already have the foundations, the building structure … all of which have to be created for a new building,” Matheny said. “We have not yet encountered a case where the community wants to save a historic school, and it couldn’t meet contemporary standards and be cost competitive.”

New buildings have “their own issues,” he added, as “aggressive schedules and tight budgets have produced some buildings already needing repairs.” His firm is working on some projects now.

“We do not reject renovation. In fact, if it’s the better way to go, we’re in favor of it,” Savors counters. “It’s just not our first priority. Our bottom line is making sure the district has a facility that allows them to provide their educational program in the best way possible.”

Finding new uses for old buildings

According to the 2013 Pew Report, 42 percent of vacant schools in the 12 cities studied have become charter schools, which have contributed to declining enrollment in cities. Between 2005 and 2011, charter enrollment grew by 66 percent in Cleveland, and 18,575 Cleveland Metropolitan School District students were attending community schools during the 2013-2014 school year, according to the enrollment projections draft report published in January 2014.

Since Zohn was hired in 2010, three schools were sold to Breakthrough Schools, and one was leased to the charter group, he said.

A quarter of vacant schools in the 12 cities studied are used by government or nonprofit agencies, and about 10 percent are converted into housing. Older, successful examples of this in Cleveland include Murray Hill School and Hodge School, which were converted into condos, apartments and art galleries in the late 1980s, and West Tech High School, which was turned into luxury apartments and lofts in 2003. The district also recently sold its East Sixth St. administration building to Drury Hotels, which plans to restore the exterior historic features.

“We supported the idea of the district selling the building to a property owner who would restore it using historic tax credits,” Crowther said. “[The district] wisely waited for the real estate market to come back.”

CMSD has also found new purposes for two buildings slated for demolition back in 2010 – East and South high schools.

The district has spent $1.5 million bringing what’s now known as the East Professional Center back in to operation to serve as headquarters for various district departments, including safety and security, athletics, food service and instruction and curriculum development, to name a few. About 150 people work there now, said Zohn, but by the time the building is complete, he estimates there will be 200 people working there.

South will serve as the records repository and archives center for the district, Zohn said, and should open in the next few years.

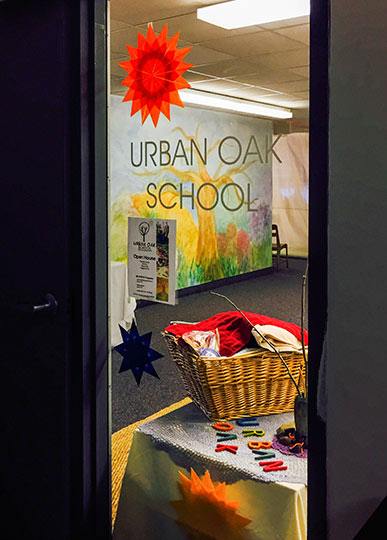

Other districts have also found new uses for surplus schools. Instead of selling the former Coventry Elementary School, which closed in 2007, the Cleveland Heights-University Heights School District leases the building to organizations that serve the neighborhood, including Lake Erie Ink, Ensemble Theatre, Urban Oak School and offices for Reaching Heights.

Other districts have also found new uses for surplus schools. Instead of selling the former Coventry Elementary School, which closed in 2007, the Cleveland Heights-University Heights School District leases the building to organizations that serve the neighborhood, including Lake Erie Ink, Ensemble Theatre, Urban Oak School and offices for Reaching Heights.

The monthly total from tenants is $9,145, which helps offset some of the operational costs. Maintenance averages $50,000 a year and utilities have ranged from about $70,200 to more than $100,000 a year for the 61,200-square-foot building, according to George Petkac, assistant director of business services.

The district worked with Cleveland Heights’ economic development director to secure tenants, which was the biggest challenge, said Steve Shergalis, director of business services.

“We are not set up to find tenants for space,” he said. “The Coventry building and property are valuable assets to our community; the ideal use for any of our properties is to support teaching and learning. If, at some point, the Board of Education decides that it’s in the best interest of the district to sell the Coventry property then we would move in that direction, but for now, we are comfortable with how it’s being used, and so is the Coventry community.”