in digital world, indie pubs aim to fill void left by waning mainstream print

Amid the cozy paper-and-paste-scented confines of Mac's Backs on Coventry is a small basket filled with booklet-sized, self-published magazines. Some of these stapled-together specimens have a charmingly slapped-together feel, filled with handmade drawings or photocopied walls of tiny text. Others are crafted with finer makes of paper, but offer the same art, poetry, short fiction, music reviews and diary-like entries of their more roughhewn brethren.

The concept of an underground press might seem antiquated when any punk with a computer and Internet access can post drawings or poetry on a website, Tumblr page or WordPress blog.

"So much creativity has gone online," says Mac's co-owner Suzanne DeGaetano.

This statement comes with a caveat: While zillions of gigabytes are available for artists, writers and would-be philosophers wanting to promote their work, self-published periodicals are still being made by folks who prefer the tactile sensation of thumbing through an honest-to-goodness magazine over moving a cursor across a computer screen. What's more, these independent publications are filling voids left by declining mainstream print.

Cleveland doesn't have a dedicated underground publishing community, notes DeGaetano. A few decades ago, the so-called "zine" movement centered locally around rock music, and since the '90s many young artists used zines as their own easily distributed creative spaces. Self-publishing has dissipated, but a do-it-yourself ethos can still be found here if you know where to look.

Mac's, for example, has an entire back shelf brimming with self-made poetry publications called "chapbooks." There's also stuff like Small Victories, a collection of short stories published by Clevelander Mark Anthony Cronin, and The Lake Erie Monster, a comic from Fairview artist John Greiner. Fresh Water spoke with a handful of self-supporting publishers doing the 'zine thing in Northeast Ohio.

Something from the Heart

Miser Magazine, a Cleveland arts and literature publication, carries some of that DIY charm that DeGaetano is talking about. The periodical is the love's labor of Nicole Hennessy and Lauren Dulay, two 28-year-olds who have been friends since meeting in seventh grade at Fairview Park Middle School.

There is no great origin story surrounding Miser's creation. The duo had been bandying the idea about for a year or two, with the simple philosophy of "making a magazine to do whatever we wanted with," says Hennessy, whose previous publishing experience included a self-made nonfiction work about Cleveland poets of the 1970s.

The name Miser, they believed, fit right in with curmudgeonly, big-hearted Cleveland. Sure, their bug-eyed, bedraggled mascot is somebody you might avoid on the street, but not that much unlike the city he represents. "Once you sat down and got to know him, you'd find out he's interesting," says Dulay, a tattoo apprentice and artist who counts Walt Disney among her inspirations.

With a budget on the nonexistent side, the friends produced their first issue in Dulay's brother's garage, where three printers were set up. They hand stapled 300 copies of the 50-page pub, distributing the issues for free in arts-friendly neighborhoods around Cleveland. Subsequent runs have gone as high as 600 copies. (Readers can also subscribe to the magazine for $35 a year.)

Miser, which publishes six times per year, is a bohemian blend of art, poetry and prose from new and established contributors. There are limits, however. One aspiring abstractionist who did not make the cut sent the magazine a copy of his homework.

"We look for anything as long as it's creative," says Hennessy, of Lakewood. "We want something from the heart."

The magazine has received an outpouring of positive responses, and its young publishers are happy to give Cleveland creatives an outlet, even if there's no real money to be made in the offing.

"We're not doing this to up ourselves in the world," says Hennessy. "We love to do it."

Yes, they 'CAN'

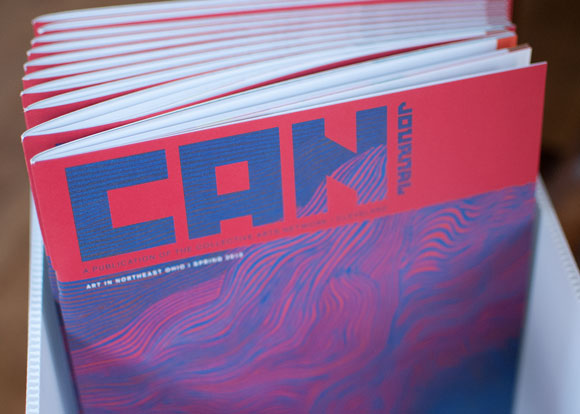

While Miser gives the perspective of artists working on the fringes, CAN Journal was created to fill another kind of void. The publication from the Collective Arts Network was founded in 2011 as a reference guide written by artists and arts organizations to reach their potential audiences.

It turned out readers liked having three dozen pages covering the schedules of their favorite galleries, as well as pieces about Art Therapy Studio, the Cleveland Institute of Art, the Print Club of Cleveland and other member organizations, along with a listing of upcoming arts festivals.

"It's a collective way of presenting the energy that's in the Cleveland art scene," says editor Michael Gill, who carries an arts journalism background that includes a stint with Scene Magazine. "There's no other publication offering that."

Bounded in colorful, high-quality paper stock, CAN Journal now has 50 galleries, studios and arts organizations providing material for the magazine. Each quarter, some 10,000 copies are printed and distributed at 200 locations throughout Greater Cleveland.

Launched by Zygote Press, a Cleveland-based independent printmaking studio, the journal has come a long way from members choosing names out of a hat to conduct interviews about each other's operations. Gill, 48, knows online blogs may contain similar information, but most aren't including schedules of the tiny galleries that don't have other promotional options.

"CAN Journal exists to provide voices to these galleries," says Gill. That voice has faded in the last 15 to 20 years as arts magazines died out and newspapers like The Plain Dealer no longer dedicate seven days of space to arts coverage. "The Internet can fill the void, but there's no one-stop shop where you can look at the broader spectrum."

That's not to say the magazine is eschewing technology. There is an online version of the journal that member organizations will eventually be able to update themselves. Still, the print version is CAN's focus, and will continue to be so.

"It's been a great project," says Gill. "It's motivating to have an impact on the arts landscape."

Thought for Food

If the arts are covered, then Edible Cleveland feeds a hunger for mapping out the local food scene. Since April 2012, the husband-and-wife team of Noelle Celeste (publisher) and Jon Benedict (editor) has been linking readers to the people making the Northeast Ohio food scene vibrant.

The seasonal publication gets down on the farm with stories about how pasture animals are raised in the region's tough climate. Other pieces explain what's on your plate, be it a recipe for sheepshead fish or all the appetizing things you can do with asparagus.

"There's no breaking news or in-the-moment restaurant coverage," says Benedict. "We want to tell stories of people involved in the food scene."

The attractive print quarterly is part of the Edible Communications family, which has similar publications around the country. The local version retains its independent chops by keeping all content regional, notes the Cleveland Heights couple.

"It's an incredible experience to know people [in Cleveland] creating and cooking delicious food day in and day out," says Celeste.

Nor is Edible Cleveland meant to be filled with impenetrable "foodie" esoterica, she adds. Instead, the magazine is aimed at readers looking for great restaurants or knowledge about choosing the right vegetable at a farmer's market.

With two children, jobs and no prior publishing experience, the most difficult part of starting the magazine was simply deciding to do it. The couple had been vacationing on Martha's Vineyard and looked to a copy of Edible Vineyard to find the best local eats. Cleveland, they thought, could use something similar.

"There was very little planning, and a lot of faith and enthusiasm," Celeste says.

That fervor has spread to the print publication's approximately 20,000 readers, and championing the energy of the local food community will always have a place here, the publisher believes.

"People care about what's happening in their backyard," says Celeste. "Our challenge is to keep that going."

In that vein, bookseller DeGaetano thinks there is a permanent place for independent print magazines in a world of increasing digital creep. "It's an art form that can't be reproduced," she says. "People keep bringing them into my store. They will always be with us."

Photos Bob Perkoski except where noted