A stinky job: Dung beetle expert hopes her work might save the declining population

Entomologist Nicole Gunter finds life in waste.

Gunter is associate curator of invertebrate geology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. She’s also a leading discoverer of dung beetles, which feast on animal droppings around the world.

In college lectures, public talks, and a forthcoming planetarium show, Gunter likes sharing the scoop on poop. Her favorite joke is, “A dung beetle walks into a bar and asks, ‘Is this stool taken?’”

Gunter’s discoveries of these barely visible bugs might not seem as impressive as the museum’s famous finds of dinosaurs and hominids. But her creatures are valuable, nonetheless.

“Dung beetles are important for healthy environments,” she says. “They’re as important as pollinators. Without them, there’d be a whole lot more dung everywhere.” The beetles bury waste, aerating and fertilizing the soil, releasing nitrogen and carbon.

But the ranks of dung beetles appear to be shrinking worldwide, like other insects, due to habitat loss, climate change, insecticides, and other challenges. Gunter hopes that documenting the beetles might strengthen the case to save them and the habitats that they share with other life.

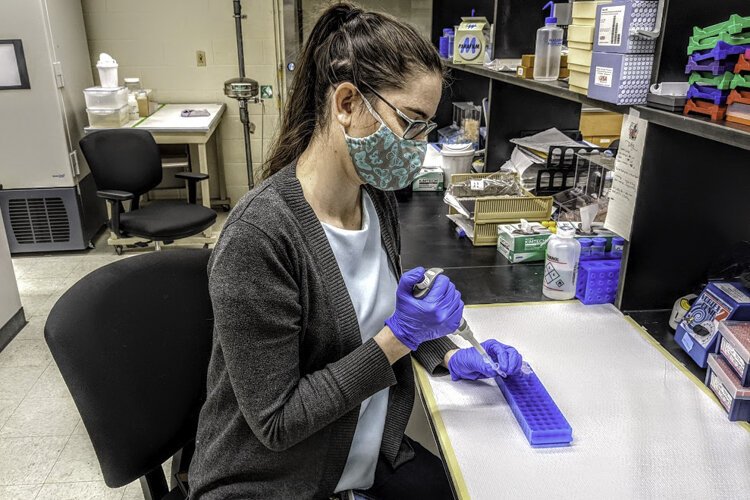

Nicole Gunter studies dung beetles at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.Before the pandemic, she used to scour the wilds of her native Australia every year for dung beetles. She had to produce her own “bait” for the traps.

Nicole Gunter studies dung beetles at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.Before the pandemic, she used to scour the wilds of her native Australia every year for dung beetles. She had to produce her own “bait” for the traps.

Gunter and her collaborators discovered 46 species of parasites—three species of jumping spiders, and 38 species of dung beetles. She also identified two genera, or groups of genus. For one species, she has found the only known specimens.

Admiring scientists have named three parasite species in Gunter’s honor, all ending with the Latin coinage “gunterae.”

Among her many honors, she won last year what the National Science Foundation calls its most prestigious award: a grant “in support of early career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and lead advances in the mission of their department or organization.”

Gunter, 37, is getting $974,412 for doing five years of research and making a show for planetariums about species diversity and distribution. The roughly 40-minute show will highlight research at the museum and elsewhere. Her show is expected to debut in Cleveland sometime after the planetarium renovations, scheduled to begin in July, are completed next year.

Nowadays, planetariums feature all kinds of science, not just astronomy. In about three years, Gunter expects to offer the show to 165 planetariums around the world with compatible software.

Dung beetles seldom exceed five milliliters, or about 0.2 inches. Gunter admires their adaptability. The parents roll droppings into little balls, then crawl backwards, pushing or pulling them to their burrows for consumption by babies and larvae.

In some of Gunter’s 29 co-written papers and six co-written book chapters, she has argued that scarab beetles, a group including dung beetles, arose about 115 to 130 million years ago, some 30 million year earlier than previously believed.

During the pandemic, she has been working partly at home and partly in a museum lab, studying her tiny finds with a microscope and sequencing their DNA. She is also doing the first studies of the feeding habits of Greater Cleveland’s nine documented species of dung beetles. She finds them at the museum’s Perkins Wildlife Center and its more than 10,000 acres of natural preserves around Northeast Ohio.

She gets all the bait she needs at Perkins or from the many local deer.

Gunter earned a doctorate from the University of Queensland and did post-doctoral work in Australia and the Czech Republic. She joined the museum in 2014 as collections manager of invertebrate zoology. She is also an adjunct associate professor at Case Western Reserve University.

She likes mingling with University Circle’s many leading researchers in varied fields. “There’s so much different expertise and connections,” she says, adding that she learns a lot from her coworkers.

For example, she recently found an uncommon species of dung beetle at the museum’s Grand River Terraces in Ashtabula County. A colleague told her that the preserve also hosts some of the region’s few remaining gray foxes. Now she’s finding that the beetle species seems to prefer that fox species’ dung. The more she can document a link between these species, the better she can argue for protecting the habitat they share.