Ticket to Ride: Stories of one teen runaway’s quest to meet the Beatles

In 1964, as Beatlemania gripped the U.S., two 16-year-olds made international headlines by running away from Cleveland to England in search of the band.

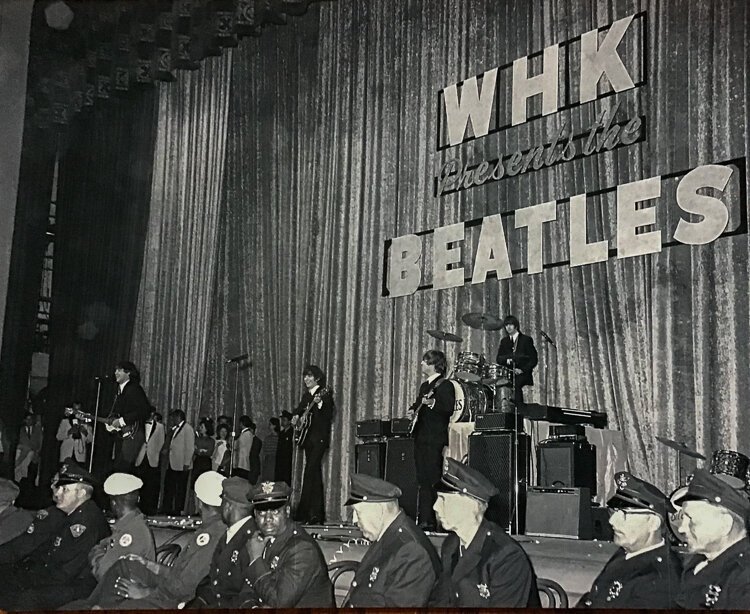

The night before they skipped town, the girls attended a Beatles concert at Public Auditorium. When screaming crowds rushed the stage, police stopped the concert, which later prompted an outraged Cleveland Mayor Ralph Locher to ban rock and roll from municipal stages for nearly two years in the city that had coined the genre’s name.

When the Beatles finally played Public Auditorium, fans drowned them with screams, broke seats and doors and windows, and tried to rush the stage.One of those teens, Janice Hawkins, now Janice Mitchell, went on to make more news as an investigator, helping to free a man convicted of double homicide.

When the Beatles finally played Public Auditorium, fans drowned them with screams, broke seats and doors and windows, and tried to rush the stage.One of those teens, Janice Hawkins, now Janice Mitchell, went on to make more news as an investigator, helping to free a man convicted of double homicide.

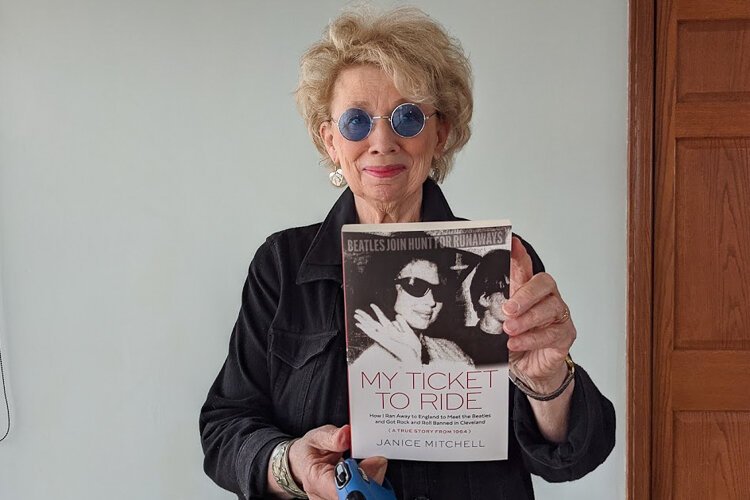

Now Mitchell has chronicled her teenage trip in “My Ticket to Ride: How I Ran Away to England to Meet the Beatles and Got Rock and Roll Banned in Cleveland (A True Story from 1964),” a $16.95 softcover from local publisher Gray & Company.

The Cleveland Heights girl wasn’t just seeking the Beatles but escaping a tough childhood.

Her parents had neglected and finally abandoned their children, and Janice was raised by a gruff great-aunt.

The girl found comfort in music. She sang in the choir at St. Ann Catholic Church and enjoyed rock and roll on the radio, sometimes through a hidden earphone in class at Ursuline Academy in East Cleveland.

At home one day in the winter of 1963-64, she heard the name of a new British group. Had she caught it right — the Beagles? But she heard the song clearly: “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

“The guitar chords and harmony electrified me,” she recalls in her memoir. “I jumped up from my kitchen chair, grabbed the radio with both hands, and held it close, straining to hear every note, every word.”

She identified with the lyrics. “I needed someone to hold my hand.”

Before long, Janice and a friend, Marty, made a daring plan. Marty would withdraw the $1,980 from her college fund, the girls would get passports, and they’d fly off to find the Fab Four.

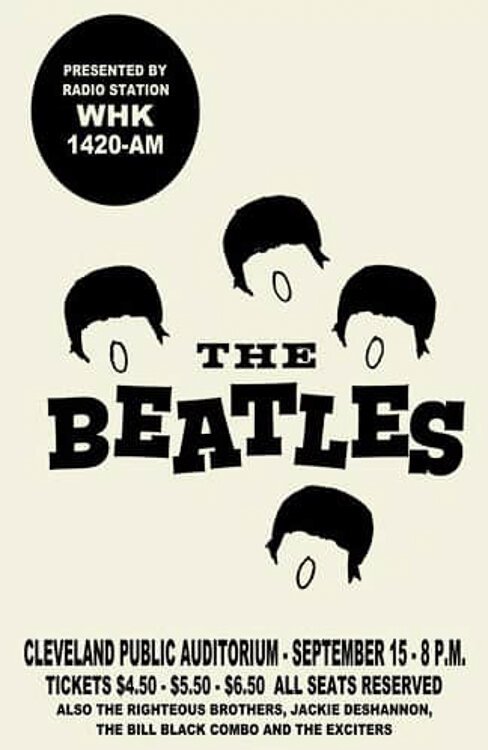

Soon they were winners in a pioneering computerized lottery to buy tickets on June 13, 1964, for the Beatles’ first show in Cleveland—a Sept. 15 gig at Public Hall. To get the best seats, Janice and Marty snuck out of their homes and spent the night before the sale at the front of the line outside Public Hall. They also set the date of their flights to London for the morning after the show.

Meanwhile, Janice had met KYW disc jockey Harry Martin at a school dance, and he'd given her a tour of the station. Now he invited her to a Rolling Stones show on June 18. Beforehand, she snuck backstage and found the band’s dressing room.

Guitarist Bill Wyman said, “Well, come in and sit down.” According to the memoir, “his brown, soulful eyes crinkled like stars.” Mick Jagger had “animal magnetism that didn’t quit.” Brian Jones “looked stressed, confused, and restless—like a wayward angel who was trying to get back to heaven but couldn’t remember how.”

Guitarist Bill Wyman said, “Well, come in and sit down.” According to the memoir, “his brown, soulful eyes crinkled like stars.” Mick Jagger had “animal magnetism that didn’t quit.” Brian Jones “looked stressed, confused, and restless—like a wayward angel who was trying to get back to heaven but couldn’t remember how.”

Janice watched the show from the wings. Afterwards, she writes, Wyman invited her to join the band’s tour. She said she couldn’t. He kissed her goodbye.

When the Beatles finally played Public Auditorium, fans drowned them with screams, broke seats and doors and windows, and tried to rush the stage. Janice clung to her seat in terror. Police suspended the show for about 10 minutes. The crowd finally settled down enough for the band to finish.

The next morning, Janice and Marty made their escape to find the Beatles. In London, they quickly found a flat and began to haunt the Soho district. “You could hear live music in all the clubs and coffee bars night after night,” Mitchell said in a recent interview. “Music was a big part of life.”

The girls also managed a brief pilgrimage to Liverpool, the Beatles’ hometown.

They never found the band. But they found friends and dates. Janice writes that she hung out with “the most fab boy,” who had “beautiful blue eyes” and mod clothes.

Meanwhile, newspapers and radio stations on both sides of the Atlantic publicized a search for the runaways. But the subjects never heard about it until three weeks into their stay.

Then a bobby approached Janice on the street. “Excuse me,” he said.

“Are you from the United States?”

“Yes,” said the puzzled girl.

“Would you happen to be from Cleveland, Ohio?”

Soon the girls were sent back to Cleveland, held in juvenile detention overnight, and released to their families. At a trial, Judge Angelo Gagliardo denounced rock promoters and teenagers’ families.

“The parents of Cleveland should hang their heads in shame that they allow their children to attend such concerts unsupervised. It is like feeing narcotics to teenagers... It could very well lead to riots.”

Gagliardo barred the girls from rock and roll concerts, and Mayor Locher banned those shows from city-owned stages awhile.

Janice grew up to be a reporter in Columbus, then an investigator in New York City. She found counterfeit products for Rolex, Gucci and other brands and investigated some notorious murders. In that double homicide case, she tracked down a witness and persuaded him to recant false testimony. The convicted man was freed eight years into a sentence of 36 to life.

The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 prompted Mitchell to leave New York. She settled in Bratenahl, investigated for the federal public defender’s office, and retired in 2013. She lives with adog named Dashiell Hammett and sometimes noodles on a piano. “I could play ‘Norwegian Wood,’” she says.

In preparing her book, she revisited England and enjoyed it again. She also encountered a 1964 article in London’s Daily Mail that quoted a Beatles spokesman: “We arranged to get Paul McCartney to see them off, but then the Embassy told us they did not want to encourage the girls. They said that if we fixed up a meeting with one of the boys, it would start a mass exodus of other American girls.”

Now Mitchell says, “I was very upset, having been denied that after everything I’d gone through to be there. Who turns down Paul McCartney? I guess the U.S. embassy.” But she admires his willingness to help.

Since the book’s release last September, Mitchell hasn’t heard from the Beatles, the Stones, or anyone else in its pages. But she says she’s heard from many readers with fond memories of Beatlemania.

Now she’s working on a book about her investigations.

Looking back on her teenage trip to England, Mitchell says “I have no regrets. It was the greatest adventure, wonderful. I’m hopeful that somebody would want to make a film about it.”

Nor does she regret her taste in music. “The Beatles are the best band ever, that’s all there is to it.”

To learn more about “My Ticket to Ride,” or order it, click here.