Meet the Cleveland nun who has been working on the frontlines of HIV/AIDS for decades

Courtesy of The Buckeye FlameSister Susan Zion.of the Ursuline Sisters of Cleveland serves as executive director of Ursuline Piazza.

Courtesy of The Buckeye FlameSister Susan Zion.of the Ursuline Sisters of Cleveland serves as executive director of Ursuline Piazza.

Not every nun lists their pronouns in their e-mail signature. But let’s be clear: not every nun is quite like Sister Susan Zion.

Since 2007, Zion—a member of the Ursuline Sisters of Cleveland—has served as executive director of Ursuline Piazza, an organization she founded to address gaps in service for the HIV-positive community.

Located within St. Augustine Manor in Cleveland’s Detroit Shoreway neighborhood, the Piazza’s mission is to educate and support HIV-positive people to live better, healthier lives—whether that means assisting clients with navigating doctor appointments, finding new housing, or just generally understanding the social services system.

Ken Schneck, editor of the Buckeye Flame, chatted with the inspiring and indefatigable Sister Zion about how this work got started, the importance of piazzas, and, yes, how this nun might be a bit different from all other nuns.

Let’s start with St. Augustine Manor. Not everyone knows their incredible history working with individuals living with HIV and AIDS.

That’s right. Since 1991, before anybody else was taking AIDS patients, St. Augustine opened their doors. Of course, for those first clients, it pretty much was a hospice. They came here and they died. But they died with dignity. Then as the medicines got better, individuals began to live longer.

By the time I came here in 2007, there might have been 14 beds in the unit. Most of the folks looked like they were getting better.

I remember meeting one of the guys and I asked him, “What are your hopes and dreams?” And he looked at me like I was crazy and said, “Well, I’m dying.” And I replied, “Well, we all are dying. But it’s not imminent.” And he said, “Really?” I said, “Really. You’re eating better. Your medicines are working.” He was getting much stronger every day. We were able to get him an apartment and now he’s doing very well. And it’s been 14 years since that first conversation.

How did you come to enter the space in 2007?

I had been working in an AIDS clinic in Youngstown with sisters who created that space. I was there for over 7 years, and it was time for me to come back to Cleveland, because this is home. When I came back, I thought, “Well, what am I going to do now with my experience?”

I was talking to a couple of people, and they said that there was an AIDS unit at St. Augustine Manor. I had never known that. So, I contacted people at the Manor and had a meeting with administrators. I wasn’t asking them for a salary. I said I would put something together myself but I needed a space to work. So, they gave me an office and phone service and they were very generous to me.

I went up on the HIV/AIDS unit and started talking to people and asked what they needed. I asked, “Do you need a support group?” And they said, “Oh no. That’s not what we need.” So that’s why we started Club 95, which refers to the goal of 95% adherence to medications.

Club 95 started with maybe eight people in a small room, and very soon we had to go into a bigger space. Before COVID, we had about 40 people who would come once a month. And not always the same 40. There’s probably a steady group of 25 people who show up.

I would just go around to people in the unit and ask what they needed, and most of what they needed was someone to rely on and someone to talk to. And that’s what I did. I started collecting donations—soaps, shampoo—and it started out small like that.

That word “piazza” sounds so central to your approach.

That word “piazza” sounds so central to your approach.

It is. A piazza is a public square in Italy, a place where everyone can come in, and everyone can sit and talk. My community was founded by Angela Merici who was born in Italy. In her writing to her followers, she said, “be a living piazza where all are welcome.”

So, when I started this program, I thought, “what better name to use than piazza?” I don’t have the red tape that other agencies have. When someone comes in to talk to me, I don’t say, “Can I see your ID?”

People don’t have to jump through hoops. Anybody is welcome here and when they come in, we’ll help them as best we can.

In your mission, you refer specifically to working with individuals who have “fallen out of care.” Talk to us about that focus.

The majority—not all—but the majority of people who are involved with Ursuline Piazza usually are in some type of recovery or are maybe using now or maybe have mental illness. For most of them, HIV is not their biggest problem. It’s usually their mental illness or alcohol and other drug use. Or they might be very poor, struggling in this economy.

I might not see people in a year. I might think, “I haven’t seen George in a while.” And then George calls me on the phone or comes in to see me. So, they usually don’t lose my number.

Tell us about those moments where you thought, “We’re really making a difference here.”

I worked with one man who got an apartment on his own and I helped him move. I got him a government phone and we made a list of the things he needed to do on his own. “You need to call your doctor and schedule an appointment. You need to make sure that you order your medications. You need to let social security and disability know your new address. And you have to call me to let me know how you’re doing.”

Well I didn’t hear from him!

So I finally went to his apartment and knocked on his door and he was so excited and relieved to see me. He said, “Thank goodness you’re here!” Well, he explained that you only get so many minutes on those government phones. He told me that every time he would call social security, he would be put on hold and it would use up his minutes. And he couldn’t even call me to let me know. So it worked out that I stopped by. Now he is doing very well. He is living and doing well. Those moments mean a lot to me.

I think the biggest thing is when I look out over Club 95 and see how well they are living. Those are the important moments for me.

Let’s talk about you a little bit. I will tell you that as a gay Jew, my interactions with nuns over my 44 years has been very limited, so I’m excited to learn more. What motivates you to do what you do? How do you talk about your calling to do this work?

To be honest with you, I don’t talk about my calling to do this work. I just don’t. If people ask me what I’m doing, I talk about the needs of the people I’m working with.

I went to an all-girls Catholic High school, and I met up with some of the girls 10 years ago for a reunion. I started telling the girls about what I’m doing. And now every month we get together for lunch, and they fill up my trunk with donations.

I don’t talk about what I do and who I am. I talk about what people can do to help folks who need help. Donations are a big part of that. We need paper products and soaps, things that clients can’t get with their food stamps. They can get candy and pop. But they can’t get toilet paper. Do you believe that? When I talk, I want people to know and understand how they can help.

Ok, but I am under the impression that it is not every sister who has pronouns in their e-mail signature. It does feel like you’re charting maybe a little bit of a different path?

<laughs> Yeah, I guess so. You’re right. <laughs> But it’s because of my experiences. I understand the importance [of pronouns]. A good number of the clients that I work with are gay, so let’s put pronouns out there. I’m sorry that the church is slow in that, but we’re getting there. I really do believe that.

For our readers who may have struggled reconciling their faith and their LGBTQ+ identity, what words of wisdom can you share?

Here’s what I say to people: My God loves everyone. That’s the God I know.

What do you want people to know about the work you are doing at Ursuline Piazza?

I want everyone to know that people who are living with HIV are just like you or me. And I want everyone to know that they can always do something to help someone else. And you feel good when you help others. So just do it.

This story is published with permission from The Buckeye Flame, where it originally ran on Friday, Aug. 27.

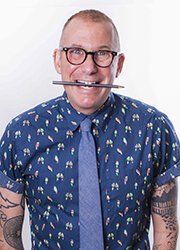

About the Author: Ken Schneck

Ken Schneck is the Editor of The Buckeye Flame, Ohio’s LGBTQ+ news and views digital platform. He is the author of Seriously…What Am I Doing Here? The Adventures of a Wondering and Wandering Gay Jew (2017), LGBTQ Cleveland (2018), LGBTQ Columbus (2019), and LGBTQ Cincinnati. For 10 years, he was the host of This Show is So Gay, the nationally-syndicated radio show. In his spare time, he is a Professor of Education at Baldwin Wallace University, teaching courses in ethical leadership, antiracism, and how individuals can work with communities to make just and meaningful change.