Phone calls and fliers: Clevelanders go back to basics to fight vaccine hesitancy

Carmella Tidmore started working with a state of Ohio COVID-19 response team to fill appointment spots at the Cleveland State University Wolstein Center’s mass vaccination site in late March. But trying to convince people to get the shot in Cleveland’s Buckeye, Mt. Pleasant, and Central neighborhoods—where vaccine hesitancy is running high—was not an easy sell.

“I had people literally tear the fliers up in my face,” she recalls of the flat-out refusal of people to take the information she was handing out at McDonald’s and Dollar General.

Eventually, Tidmore found business and apartment building managers willing to post the fliers. Then, in private, people started picking up the notice for the vaccine and calling the phone number with questions.

Mariano Collazo asks some questions about the vaccine to Jessica Centeno and Jennifer Sobrowski from Neighborhood Family Practice."I had an elderly [Black] lady say she 'really wants the shot but is afraid of needles and didn't have transportation," Tidmore recalls. "I said, 'you know what, I’ll take you.' So, I took her and another lady. When I dropped her off [after] she said to those in her building, 'It didn’t hurt, you guys. You better get signed up with Ms. Carmella. I think God sent her to me.'"

Mariano Collazo asks some questions about the vaccine to Jessica Centeno and Jennifer Sobrowski from Neighborhood Family Practice."I had an elderly [Black] lady say she 'really wants the shot but is afraid of needles and didn't have transportation," Tidmore recalls. "I said, 'you know what, I’ll take you.' So, I took her and another lady. When I dropped her off [after] she said to those in her building, 'It didn’t hurt, you guys. You better get signed up with Ms. Carmella. I think God sent her to me.'"

“It's about the groundwork,” says Tidmore. “I have to build relationships to get them to trust me."

As millions of Americans have lined up to get vaccinated, public health and government officials are concerned about the widening gap of vaccination rates between racial groups. Of the 3.36 million people in Ohio who are fully vaccinated, a relatively small number (335,116) are Black, for example.

In April, the Centers for Disease Control granted $105 million to the State of Ohio to expand access and acceptance of the vaccine—75% of the funding is going to organizations who are hiring individuals like Tidmore to increase the vaccination numbers among racial and ethnic minority groups.

The work of vaccine “angels” like Tidmore comes as the COVID-19 national vaccination strategy shifts from mass vaccination sites to the next phase in the rollout: Trying to convince reluctant Americans to get vaccinated.

Organizers say that barriers like isolation because of the pandemic and lack of proximity to medical establishments in parts of Cleveland make volunteers and paid staff members like Tidmore essential. They’re picking up calls to hotlines, knocking on doors, handing out fliers, and arranging for transportation to the Wolstein Center, or driving residents themselves if necessary.

Where hesitancy runs high

The data from the state's weekly reports on who is getting the shot reflects a larger trend in the country: People of color and white, evangelical Christians continue to sit on the sidelines instead of getting vaccinated.

Mistrust of vaccinations in the Black community has not dissipated, even with 50% of all Americans receiving their first dose, says Tiffany Allen-White, director of community relations and internal operations at Burten, Bell, Carr, Development, Inc., an east side community development organization.

"It has not gone by the wayside," she says. "Even though Black and Brown communities have been heavily impacted [by COVID-19], it is still mistrustful. We’re saying, 'should you want it, we want to make sure you have access to it, just like anyone else. We are not keeping you from something that is your right.'"

Tidmore says she is hearing concern among Black residents about National Guard personnel administering the shot, but also interest in receiving the shot from doctors and pharmacists.

"We have heard from our community that a lot are just nervous going to get a shot," says Allen-White, adding that the distance between downtown and neighborhoods where car ownership rates are low also act as a barrier. Pop-up vaccination events in the Central and Buckeye areas, like those held at local churches, are one way to lower that barrier, she says.

An act of faith

Maureen Dee, a volunteer with the Hispanic Roundtable who has been signing people up for the shot in the Latinx community, agrees that church pop-up events are influential. These temporary vaccination events, like the one recently held at La Sagrada Familia on West 78th Street and Detroit Avenue, help decentralize and bring the vaccine into a more familiar setting, she says.

Houses of worship have been cornerstones in the fight against the disease, Dee says, adding that St. Michael's Church at Scranton and Clark Roads contacted the Hispanic Roundtable early in the pandemic when they had an outbreak among the largely Latinx parishioners.

"There was a lot of worry about the virus, so they requested that people speak during mass about the options and, in general, protective behaviors,” Dee says. “So, we're working with them."

Trying a new strategy

Enlisting the once-hesitant to persuade friends and family to get the shot is a strategy worth considering, says Earl Pike, executive director of University Settlement, Slavic Village's organizational “hub” in the Greater Cleveland COVID-19 Rapid Response network.

"What we really need is grandmothers and Uncle Ted saying, 'I got the shot,'” explains Pike. “We need a block-by-block strategy. We almost need to send people out with backpacks [filled with] syringes.

"With any behavior change, there are the people who are on the fence," Pike adds. "It's going to come down to, what are the 10 people closest to my life doing?"

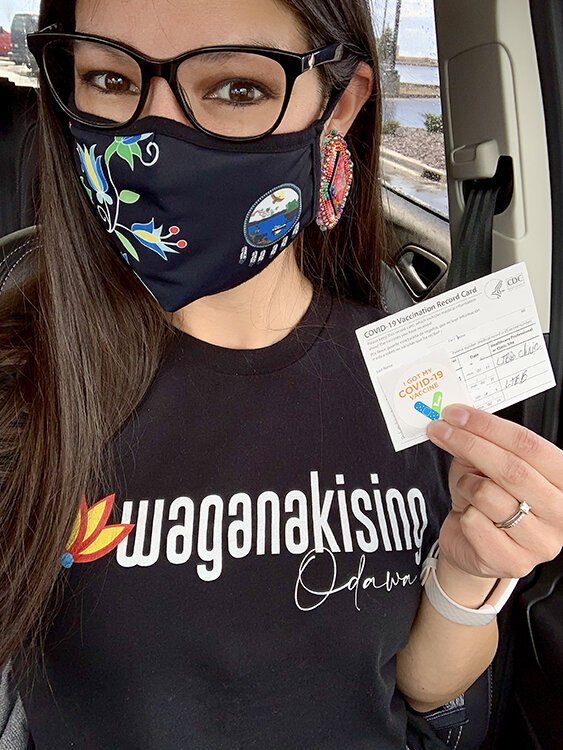

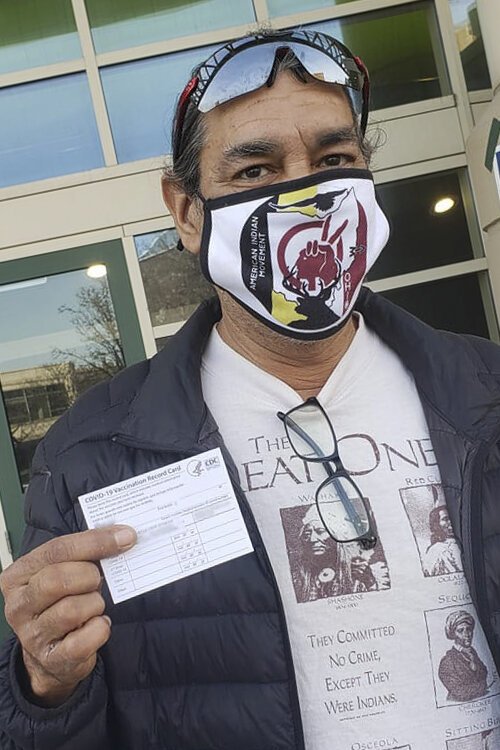

Cynthia Connolly, a volunteer working with University Settlement to reach Native Americans living in the Greater Cleveland area.Though harder to predict, Dee, Tidmore, and Cynthia Connolly, a volunteer working with University Settlement to reach Native Americans living in the Greater Cleveland area, have seen the power of networks to transform hesitancy into resolve.

Cynthia Connolly, a volunteer working with University Settlement to reach Native Americans living in the Greater Cleveland area.Though harder to predict, Dee, Tidmore, and Cynthia Connolly, a volunteer working with University Settlement to reach Native Americans living in the Greater Cleveland area, have seen the power of networks to transform hesitancy into resolve.

"Word-of-mouth takes over, because family members tell other family members," Dee says. "Before I knew it, I was training [a woman who signed up for a shot] who was reaching an immigrant community living in a trailer park in [the suburbs]. I had three calls from restaurant owners, operators of Mexican and Central American places, who are interested in signing up their staff who work in the kitchen. Little by little, we're making inroads in a community that otherwise we have difficulty reaching or hearing from."

Delivering on its promise

Connolly has observed that using cultural norms such as the protection of elders and “first language speakers” has helped. So has the promise of healing and a return to normal.

"I think a big, encouraging factor is, with more nations being vaccinated, as we've seen in the Navajo nation, cases have plummeted," Connolly observes. "A lot of us have family who were decimated by this."

Returning some social events, such as their annual Pow Wow or a simple cookout, is a motivator for some.

Burten, Bell, Carr was provided $60,000 from the state for its vaccination outreach, and Allen-White says most of the funds will be used for paid staff like Tidmore.

Additionally, residents can earn a small stipend going door-to-door, dropping fliers in mailboxes. Tidmore has signed up 75 residents so far, and BBC has distributed more than 700 fliers. In addition, the budget covers time for BBC to post announcements using social media and broadcast daily announcements on radio station WOVU 95.9 FM.

Dee estimates she and four other volunteers working without compensation have signed up 3,000 people for the shot so far.

Of the 538,170 people who had their first shot of COVID-19 vaccine in Cuyahoga County, 87,374 are Black (23% of the Black population), 1,296 are American Indian (40% of the Native American population), and 22,831 are Hispanic or Latino (29.5% of the Latinx population), according to state data.

They agree the work is necessary, if not sufficient, to reach the hardest to reach.

"It’s not a silver bullet, but it would not work without it," Connolly says. "A lot of people are nervous about going to crowded indoor places and would rather go to their local drug store. That’s a whole other challenge—making sure there is equitable access closer to their homes. That would be a huge step."

In the long run

In a time of isolation and with hesitancy still running high, even a six-mile round trip from Slavic Village, Buckeye-Woodland, or Central neighborhoods to the Wolstein Center represents a barrier that should not be underestimated, Pike says.

With more nations being vaccinated, as seen in the Navajo nation, an encouraging factor is cases have plummeted.In Slavic Village, Pike says many residents feel the vaccine just isn’t accessible in the neighborhood, which could mean transportation and childcare expenses and lost wages for taking time off. “The access [to the vaccine] may be the pharmacy six miles up the road,” he says. “So, you can’t compare that vaccination to my vaccination as a straight white guy [living in the suburbs] because mine didn’t cost a dime.”

With more nations being vaccinated, as seen in the Navajo nation, an encouraging factor is cases have plummeted.In Slavic Village, Pike says many residents feel the vaccine just isn’t accessible in the neighborhood, which could mean transportation and childcare expenses and lost wages for taking time off. “The access [to the vaccine] may be the pharmacy six miles up the road,” he says. “So, you can’t compare that vaccination to my vaccination as a straight white guy [living in the suburbs] because mine didn’t cost a dime.”

President Biden, recognizing some of those barriers, introduced a $500 per employee tax incentive in late April for businesses that allow employees to take time off for vaccination purposes.

Locally, United Way’s 211 Help line provides support for registration and transportation options, including a free Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) bus pass and ride-share services to mass vaccination sites like the Wolstein Center and a newly established site at MetroHealth facility in Maple Heights.

For volunteers like Dee, hearing back from those she served that they are having conversations with family and friends about their experience, is a form of currency being paid forward.

"I get a lot of gratitude," Dee says. "People who are grateful for the help in making it easy and accessible for them. They tell me their mom won’t get it and a few weeks later they call and say [the parent] changed their mind. No one’s being forced, but it's good to be available because they will loop back and have conversations with their families and some will call and say, 'Okay, I’m going to take the plunge."

This story was sponsored by the Northeast Ohio Solutions Journalism Collaborative (NEOSOJO), which is composed of 20-plus Northeast Ohio news outlets including FreshWater Cleveland.