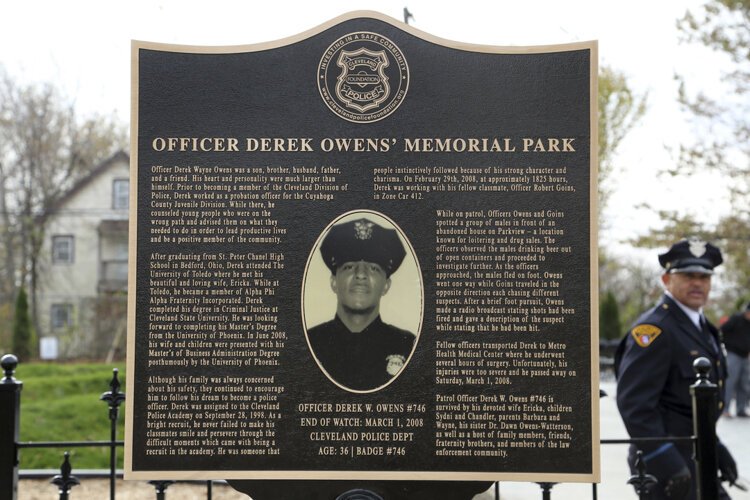

A new park in Buckeye carries on the memory of fallen police officer Derek Owens

An old adage states that “heroes never die”—and a new park is doing it justice by making sure the memory of fallen police officer Derek Owens stays alive for many years to come.

Located in Cleveland’s Buckeye/Woodhill neighborhood at 10404 Parkview Ave., the 18,022-square-foot park sits on three formerly vacant parcels of land—one of which was the house where Owens was shot and killed in 2008. The park features a playground donated by the Cleveland Browns and special touches like a mindfulness labyrinth and a Little Free Library shaped like an old-fashioned police call box.

Located in Cleveland’s Buckeye/Woodhill neighborhood at 10404 Parkview Ave., the 18,022-square-foot park sits on three formerly vacant parcels of land—one of which was the house where Owens was shot and killed in 2008. The park features a playground donated by the Cleveland Browns and special touches like a mindfulness labyrinth and a Little Free Library shaped like an old-fashioned police call box.

Though the park officially opens in spring 2020, a dedication ceremony was held Nov. 9 to celebrate the park's completion and honor all of the organizations and community members who came together to make it happen.

“It’s truly been a labor of love from the community—from the Cleveland Police Foundation to environmentalists to people committed to social justice,” says Jay Westbrook, special projects manager for Western Reserve Land Conservancy. “It truly hit on all the cylinders on that front.”

He’s not exaggerating: The project has been in the works for several years, having originated with Kimberly Fields of St. Luke’s Foundation and Nelson Beckford of the Cleveland Foundation. Over time, other partners such as LAND studio, the Western Reserve Land Conservancy, and the Cleveland Police Foundation came on board (with the Cleveland Police Foundation buying the property and committing to the ongoing maintenance and upkeep).

Along with purchasing the property, the Cleveland Police Foundation committed to raising the funds necessary to create the park (estimated at between $180,000 and $250,000).

Along with purchasing the property, the Cleveland Police Foundation committed to raising the funds necessary to create the park (estimated at between $180,000 and $250,000).

Captain Keith Sulzer says that they were able to raise $140,000 of the total amount and that the rest was garnered via in-kind donations—from the carpenters and painters unions that put together the Little Free Library to the cement masons that donated labor and 70 yards of concrete for the labyrinth.

“The only reason this happened was because we had that help—the labor unions were absolutely phenomenal,” says Sulzer. “If [the Cleveland Police Foundation] would have raised over $200,000, the park wouldn’t have the meaning it does today, because so many people were able to pitch in. They can drive by this park and say, ‘I helped build that.'”

represents prayer and reflection, while the serpent mound is meant to symbolize the journey of life. A pendulum representing the passage of time swings near three sandstone benches repurposed from homes demolished nearby; the benches represent Owens’ family members, wife Ericka and children Sydni and Chandler.

represents prayer and reflection, while the serpent mound is meant to symbolize the journey of life. A pendulum representing the passage of time swings near three sandstone benches repurposed from homes demolished nearby; the benches represent Owens’ family members, wife Ericka and children Sydni and Chandler.

“This project is on par with the Maya Lin garden at the Cleveland Public Library,” says Westbrook. “It may have different features, but both are very significant in the impact they have on the psyche of the visitor.”

Westbrook hopes that the park will also play an important role in bettering police-community relations, and Sulzer says there will be programming to that end—from yoga in the labyrinth to officers reading to children in the community space.

"Here we are in the heart of the black community, and its people are saying that, 'We treasure this officer and his gift and his sacrifice,'" says Westbrook. "From now on, kids will be playing on the playset, and parents can sit in a reflective location hearing the birds chirp. The park is turning an ugly, tragic incident into a healthy and beautiful site that benefits the community."