A tree grows in Old Brooklyn (and it's the stuff of legends).

Every tree tells a story, but this one is for the (record) books.

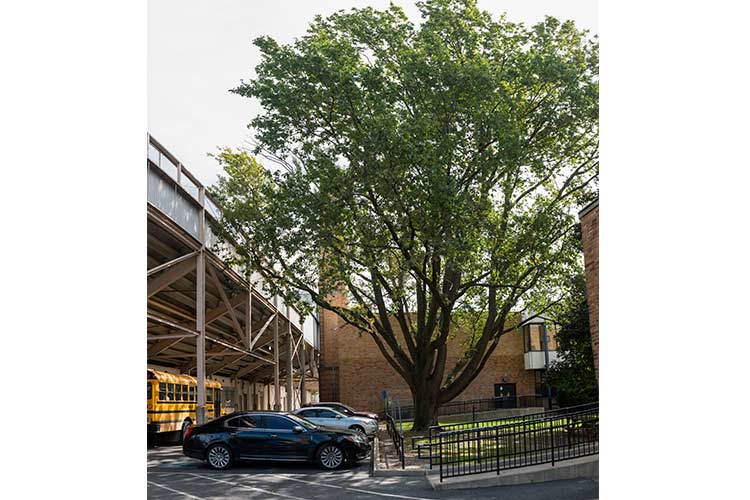

Aptly located behind the athletic complex at James Ford Rhodes High School, the Jesse Owens  Olympic Oak tree pays homage to the track star of the same name who brought home four gold medals from the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Owens' victory was two-fold—not only was he the first person ever to win four gold medals at one time in Olympic track history, but as a black competitor in Nazi Germany, he was able to powerfully disprove Adolf Hitler’s idea of Aryan supremacy.

Olympic Oak tree pays homage to the track star of the same name who brought home four gold medals from the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. Owens' victory was two-fold—not only was he the first person ever to win four gold medals at one time in Olympic track history, but as a black competitor in Nazi Germany, he was able to powerfully disprove Adolf Hitler’s idea of Aryan supremacy.

To commemorate Owens’ accomplishments, the German Olympic Committee gifted him four English oak saplings—which he later planted in Berlin, behind his childhood home, at The Ohio State University, and at James Ford Rhodes High School. (Owens attended East Tech, but was bused to James Ford Rhodes High School for track practice.)

Over time, the trees in Berlin and his one-time home were lost to the war and demolition, respectively, and no one is sure of the exact whereabouts of the tree at OSU, so it’s safe to say that James Ford Rhodes High School remains the only surefire spot to admire one of Owens’ Olympic Oaks.

And right now, both Owens and his Old Brooklyn-based tree are having a moment.

In July, Governor John Kasich announced that Ohio’s newest—and largest—state park would be named after Jesse Owens, and in early August, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) hosted a Q&A between the Plain Dealer’s Bill Livingston and Owens’ second cousin, Tyrone Owens, titled, .jpg) “Points of View: The Legacy of Jesse Owens.” (The tree is also featured prominently in Cyprien Gaillard’s Nightlife installation, currently running at MOCA through September 30.)

“Points of View: The Legacy of Jesse Owens.” (The tree is also featured prominently in Cyprien Gaillard’s Nightlife installation, currently running at MOCA through September 30.)

Tyrone Owens—Jesse’s second cousin—is also getting recognition. The former women’s track coach for James Ford Rhodes High School, Owens will be inducted into the James Ford Rhodes Hall of Fame on October 12 alongside Nicole Smith, another esteemed athlete and James Ford Rhodes alum who later played professional basketball in Europe.

Tyrone began his career with Cleveland Metropolitan School District in 1978, jumping from school to school until he was selected as the Rhodes track coach in 1982. Tyrone describes his 24-year-long career at Rhodes as "exciting"—having sent all types of students to state championships, many of whom received scholarships.

He has also played a big part in helping preserve the legacy of his second cousin, Jesse—whose story began in Oakville, Alabama, in 1913 and hit its stride in the 1920s after the Great Migration, during which Jesse’s family moved to Cleveland to find work. While Jesse’s other siblings had to get jobs because of the Depression, it was clear from the beginning that Jesse could run at unbelievable speeds. Charles Reilly, Jesse’s coach at the now-defunct Fairmount Junior High School, is credited to discovering his incredible talent.

“Even at his first track meet, his times were world-class, which was unheard of,” Tyrone says.

At the MOCA event in August, Tyrone shared his collection of Jesse Owens memorabilia, including a picture book from the 1936 Olympics and other original photos.

At the MOCA event in August, Tyrone shared his collection of Jesse Owens memorabilia, including a picture book from the 1936 Olympics and other original photos.

And, of course, the treasure of the Jesse Owens collection at is the Jesse Owens Olympic Oak. The tree received a plaque in October 2012 as part of a dedication ceremony held by the Old Brooklyn Community Development Corporation (OBCDC), and last year, OBCDC successfully worked with the Holden Arboretum to clone the Jesse Owens Olympic Oak.

Now Tyrone is turning his attention to spotlighting other hometown sports heroes—in hopes of encouraging future generations of Cleveland athletes. He and Smith have joined forces on a book and documentary that will tell the stories of Olympians like David Albritton, who followed Jesse from East Tech to The Ohio State University and to the 1936 Olympics, where he received the silver medal for high jump. Other athletes profiled will include Vivian Brown, an East Tech grad who competed in the 1964 Olympics, and Eleanor Montgomery, a John Hay High School alum who also competed in the 1964 Olympics.

“We've started doing the groundwork, and we hope we don’t leave anyone out that’s deserving. There are several other Olympians that went to East Tech and no one has heard of them,” Tyrone says. “These stories have just not been told."

This article is part of our On the Ground - Old Brooklyn community reporting project in partnership with Old Brooklyn Community Development Corporation, Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, Cleveland Development Advisors, and Cleveland Metropolitan School District. Read the rest of our coverage here.

.jpg)

.jpg)