Trending: urban wineries

Cleveland has amassed a hefty repertoire of craft beer vendors, some of the best in the Midwest, from the solid selection at Great Lakes Brewery to the DIY options at the Brew Kettle. Hence it’s no surprise that at the 2015 Great American Beer Festival, five of the top medal winners were from greater Cleveland. Make no mistake: this is a beer town.

But what about wine?

Although the collective brewer’s shadow may eclipse the Cleveland market, local winemakers are gradually setting up shop and moving in vats and stainless-steel tanks by the truckload while others are planting vines in urban neighborhoods. All of it is culminating to form the future of Cleveland wine.

Cleveland's Wine Companion

The number of wineries in Ohio has risen dramatically, from 43 in 1997 to some 150 in 2013. Ohio wines are mostly produced by wineries along Lake Erie’s coastline, from Debonne’s medal-worthy vinifera vintages to the sweet offerings of Heineman’s. Northeast Ohio vintages are no longer a secret to national - and even international - tasters. Anyone in doubt can ask Destiny Burns, a Cleveland Heights-based entrepreneur and wine enthusiast.

“Northeast Ohio wine is already a big thing,” she says, “but you have to go fifty miles from here to reach it. And not everybody here in the city is willing or able to make that trip.”

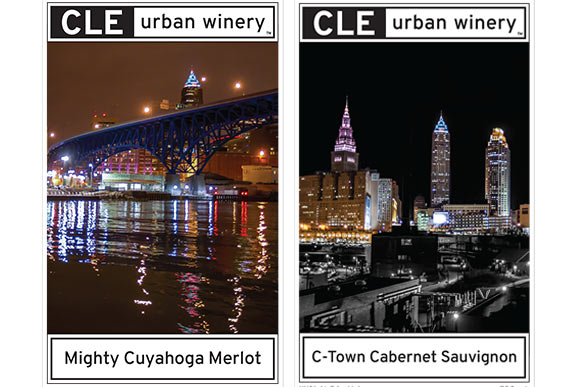

Last November, Burns, a former Navy cryptologist-turned-winemaker, started building CLE Urban Winery, an inner-city response to the traditional bucolic vineyards dotting the north coast. Modeled off a Maryland winery Burns used to frequent during her years working in Washington, D.C., CLE Urban is the “wine companion” to Cleveland’s craft beer scene: one complete with its own fermentation room and lab analysis space (both of which are open to curious guests). Burns plans to offer about a dozen house wines, each with their own themed homage to the city, including one to pair with the venerable Great Lakes Christmas Ale.

CLE Urban Winery tasting bar rendering

CLE Urban Winery tasting bar rendering

With traditional vineyards requiring significant acreage and funding reaching upwards of seven figures, becoming a grape grower is no easy feat. The alternative is to ditch the idea of planting a vineyard and operate a wine production facility much like a brewery, importing grapes as brewers do hops.

Since last September, Burns has been renovating a vacant space on Lee Road in Cleveland Heights by erecting walls to facilitate a tasting-room and a 70-foot, industrial-chic bar tessellated with wine corks. She's also lugging in the required equipment such as stainless-steel tanks. Though Burns has included a small kitchen for cutting cheeses and charcuterie, CLE Urban’s utmost raison d'être is to craft good wine with a fast turnaround, “meant to be drank young.” She hopes to have the first batch ready by the beginning of next month.

Though CLE Urban is the first of its kind for the area, dozens of urban wineries have sprouted up throughout the country, from New York to Portland, with a similar aim in mind: to bring locally-made wine closer to city dwellers. The idea appeals to Burns.

“I’m definitely not a farmer,” she admits, “and I don’t want to be a farmer. Not even … ,” she holds up her hand in jest, “I might break a nail.”

Her partner-in-wine, Dave Mazzone, a former Debonne winemaker fluent in the language of the craft, says that CLE Urban’s plan to “demystify” wine is more easily achieved when rooted in the neighborhood versus wine country. With his decades of experience creating wines from Rieslings to cabernets, Mazzone is giddy about what he and Burns can do for Cleveland’s future wine market.

“I think that we’re on the cusp of having a sort of resurgence of an identity,” he says, “of not just being great growers, but holistically producing just great beverages.” He adds that the craft has a regional history.

“It’s kind of natural that a wine country has sprung up here again.”

Of Times and Grapes Gone by

Ohio, particularly Northeast Ohio, used to be the number one state in grape production in the nation. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, German grape growers settled along the lake to benefit from the fertile soil, which is ideal for cool-climate varietals, the French-American grapes and vinifera (the variety used for cabernet sauvignon and Riesling). The barrels of vino produced in Northern Ohio led to the area’s sobriquet: “The Lake Erie Grape Belt.”

Though the market plummeted during Prohibition, when many vineyards turned to making grape juice, there was a strong resurgence of the so-called urban winery in the 1980s, which was influenced by the French in-house-wine-fabricant concept of the garagiste (literally “garage owner”). Most of these winemakers cite a two-fold reason for producing in the city: cheaper production and access to consumers. The City Winery in Manhattan, a hot East Coast example of the urban resurgence, claims they were built largely to “stand out from the Long Island wine world” that surrounds them.

Barrel tasting party at North Coast Wine Club

Barrel tasting party at North Coast Wine Club

“It’s sort of like coffee shops. There’s one, and then there’s twenty of them,” says winemaker Tom Radu, who is also president of the North Coast Wine Club in Solon, wherein members can make wine utilizing commercial style equipment. “It’s indicative that people like to have a closeness to their food source. And also, they want to have a hands-on approach to it, as well. Nonetheless, you go where the people are.”

Radu, who produced 11 different wines in 2015 with his small team, considers the dilemma of tradition versus urban, posing: is being “urban” worth sacrificing what traditional vineyards offer? Just to call a merlot "local"?

Though Lake Erie’s coast includes pockets of soil viticulturists dream of, operating a vineyard and production plant is difficult in urban areas due to space constraints and zoning restrictions. Hence an urban winemaker often has no choice but to import grapes, which Radu notes, one must do very carefully.

“As I see it, the type of wine, and caliber of wine, you want to make determines the type of grape you’ll need to source,” says Radu. “Some of them you can source locally, and other ones you just can’t.”

Hough Vines, Award-Winning Wine

Although CLE Urban will be importing grapes from all over the country, there are a few northeast Ohio grape growers, including entrepreneurs Jim Conti, of Cleveland Jam, who is converting Old Brooklyn sites into grape-producing greenhouses.

Others operate in more surprising neighborhoods.

Mansfield Frazier of Vineyards of Chateau Hough

Mansfield Frazier of Vineyards of Chateau Hough

Located on the site of a former crack house on East 66th Street and Hough Avenue are the Vineyards of Chateau Hough, an 11-row vineyard no bigger than a baseball diamond. Owned by the 83-year-old Mansfield Frazier, Chateau Hough is Cleveland’s lush poster child of the inner-city vineyard. The staff includes more than 50 ex-cons and volunteers from a nearby halfway house. No surprise that, considering Frasier is a former convicted con man-turned community philanthropist.

The vineyard began as an effort to put the vacant lot near his home to good use. Frazier enlisted the help of his friend Radu and business partner Michael Conti, along with a $15,000 grant from the city, and set up shop. The venture now produces, on average, hundreds of bottles a year.

“Here, our grapes just shoot out of the ground,” says Frazier in his trademark gravelly voice. “And that’s how we get award-winning wine.” Chateau Hough garnered its first ribbon in 2014.

Unlike Radu and Burns, Frazier grows the grapes and produces the wine off-site, but that will soon change. This year, noticing a spike in the local market, Frazier is ramping up. Along with more than 25 more acres of grapes, he’s building a fully functional winery right next to where volunteers harvest the grapes in a building nicknamed "The Library." Frazier is so adamant about this development that he’s halting any other expansion until the winery is finished.

“If you can make a wine that is as good as any other wine,” Frazier says, “then why would people want to buy some wine that’s imported from California, instead of one made right in your neighborhood? To me it just makes sense.”

Looking ahead, Frazier hints at tiptoeing into the craft beer market.

“Wine is the same thing as beer,” he says matter-of-factly, “except that nobody cares where the hops come from.”

Cheers to Community

While CLE Urban awaits its July 1 grand opening, which will be a weekend-long event, Burns is looking over cork designs and labels festooned with names such as “Rust Belt Rose” and “Lake Effect Snow Vidal Ice Wine” for Mazzone’s offerings. Though the duo will be importing grape varieties from vineyards all over the world, CLE Urban will also aim to source locally.

Burns isn’t stopping at wine sales. Following in Frazier’s philanthropic footsteps, she also plans to share profits with organizations such as Greater Cleveland Fisher House or the National Fallen Firefighters Foundation as giving back to the community was in part the impetus of CLE Urban.

“Also,” Burns quips, “I just like wine.”