Organizers must restore trust to combat Glenville's lead crisis, with federal grant's help

Among the water-safety advocates and tie-sporting health commissioners, no one at the Glenville Rec Center gym seemed more passionate about lead than Kevin Conwell. It’s the first evening of Lead Safety Week, and the Cleveland Ward 9 Councilman steps up in his black vest and slacks to speak to a handful of attendees, a spatter of them residents. The audience, a conscious observer might note, could equate to less than 5% of Glenville’s lead-affected population.

“This problem is about our children!” Conwell, the Glenville native who’s been on City Council for 18 years, says into the mic. A cluster of balloons behind him read, “Get kids 6 yrs old and younger lead tested.” “We live through our children,” Conwell continues, “they are our future. We gotta go door to door, then. As Jesus said, ‘We gonna have to go fishin’.’”

Conwell’s enthusiasm isn’t just piggy-backing off a national awareness campaign.

The week before, on Oct. 1, it was announced that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development was awarding the city of Cleveland a $9.7 million grant to specifically aid four census tracts—the majority of them in Glenville—in combating the city’s historic problems with lead poisoning (the largest grant in Ohio, second to Columbus). Although city officials appear unsure of what the bulk of a 750% funding increase will be allocated for, hundreds of thousands of dollars are being used as a salve to a long-running gap: resolving issues of trust between at-risk Glenville residents and “badge-wearing” governmental officers who come rapping at their doors.

Staffing 14 new community engagement specialists at community development corporations around Cleveland—four in Glenville, along with others at Clark-Fulton and the Stockyards—officials believe will encourage even the most skeptical residents to seek lead remediation efforts. Such specialists, says Tania Manesse, director of Cleveland’s Department of Community Development, will also put legal pressure on area landlords, “holding them accountable for the condition of their home.”

“Frankly, right now everyone knows the biggest issue,” Manesse says. “We just don’t have enough contractors. We don’t have enough people trained to do this work. I see this as an opportunity to train.”

Bolstering the 380-member Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition, the cluster advocacy group at the forefront of Cleveland's lead issues, and creating a Lead Safe Resource Center, Manesse says, is only half the battle. The remainder, she says, is out of her hands.

“It’s not that [residents] don’t care,” she says. “An issue as big as this has to do with the community saying, ‘This is going to be a priority.’ ”

‘Will they take my kids?’

If I’m a resident of Glenville, and I live in a home that is suspected to contain lead (and was built before 1978, when lead paint was banned in the United States), a number of things could happen.

If I’m an adult, and I get sick—either from wall paint or windowsill scraps—I may experience an array of symptoms, ranging from abdominal cramps to random memory loss. If I’m a child, and I get sick, the diagnosis could be a lot more disheartening: High levels of lead in my blood could mean stunting my growth and causing learning difficulties. If I’m a pregnant woman, enough lead could result in a miscarriage.

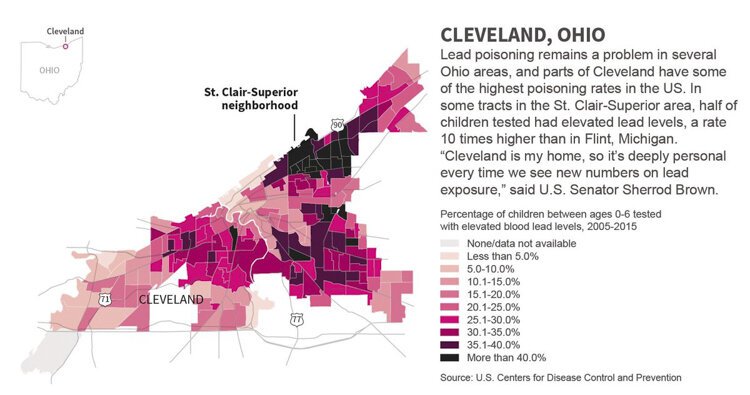

A 2017 study of Cleveland children from the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University found that nearly 13% of kids under 6 had lead in their blood “at or above the level” where officials urged action. Just two years before, nearly one out of four were estimated to be poisoned. At that time, nearly 80% of Glenville children had “dangerous” levels of lead in their blood. Such reportage influenced critics of city officials to suggest that Glenville children were essentially “being used as human lead detectors.”

“You can’t broadstroke this issue,” says Kim Foreman, executive director of Environmental Health Watch, an advocacy group at 5802 Detroit Ave., Cleveland. “I mean, some [residents] don’t want to even let the city in. ‘Will they find hazards just to take my money?’ ‘Will they take my kids?’”

A lifelong social activist and health educator in Northeast Ohio, and director of Environmental Health Watch for 21 years, Foreman has earned her stripes as an expert on the city’s lack of lead crisis resolution.

In fact, well before HUD granted its $9.7 million, Foreman had been advising the Lead Safe Coalition’s multipronged Healthy Homes Initiative, a $3 million effort to bolster neglected houses everywhere from Clark-Fulton to Mt. Pleasant. And in the past year, Foreman has been working hand in hand with 17 Action Team Members, on-the-ground volunteers creating rapport with residents, as Foreman says, at “beauty shops or at their front doors.”

With her underlying focus on preventive lead education, rather than the reactionary process of the past, Foreman knows that bettering the 1,200 Cleveland kids at risk truly does come down to hard dollars. Glenville, though it’s ground zero, is merely the beginning of a wider array of outreach, she says.

“I can’t impact the whole city,” Foreman says, “unless I have the resources.”

Knee deep in renovations

Leon Stevenson’s own personal lead crisis happened in 2015. As the owner of two rental units, Stevenson, 67, was approached one day by one of his tenants after she returned from a doctor’s visit: Her 5-year-old daughter was sick. The catch?

“She had only been in that place for two weeks!” Stevenson said, standing outside the gym of the Glenville Recreation Center. “But [the officials] didn’t care. They were on me. By the virtue of her living there, they put it on me.”

Following the woman’s complaint to the Health Department, Stevenson’s properties were under inspection for possible lead poisoning—a process that would extend seven months into summer 2016. He asked Conwell to “speed things up a bit,” yet by July of that year, it was too late: Stevenson had lost six months rent, roughly $10,000. All of his tenants had vacated, and Stevenson had to find other work in home remodeling. His tenant had admitted the lead came from her previous house, but Stevenson was already knee deep in his own renovations.

“All I could do was deal with it,” he said. “Sometimes your hands are tied, and at that time mine sure were.”

After repainting stairwells and replacing old window sills and porch doors, Stevenson came to a sort of double-edged sword situation: He could rest assured that his properties were lead-free—thus gaining home equity—yet had hit a deep financial setback. Under the new citywide lead prevention law, in effect come 2021, all landlords in Glenville will, like Stevenson, have to undergo mandatory lead inspection.

Since Stevenson’s own crisis, he’s decided to play offense, volunteering in street outreach and code enforcement for Ward 9. Part of his push, he owes to Conwell.

“That man, he fights for all the right things,” Stevenson said. “If you need money? I swear, he’ll go right into his own bank account to help you out.”

To the mountaintop

In the middle of Lead Safety Week, Conwell attends a press conference in Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson’s Red Room to help formally accept HUD’s $9.7 million grant. To the right of Jackson at the podium, Conwell nods affirmingly when Jackson says, “All of this would not have happened without the leadership in City Council.”

When a National Public Radio reporter questions Jackson about a plausible end to the crisis, the mayor refers to the future of the Lead Safe Resource Center, and echoes the predictions of past administrations. “We’re going to have a lead-safe Cleveland in 10 years,” he says.

Mayor Frank Jackson stands with Joseph Galvan, regional administrator of the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development, and Kevin Conwell, Ward 9 councilman, to receive a check for $9.7 million for Cleveland’s lead crisis.After the check-holding photo-op, Conwell sticks around the Red Room to greet members of HUD he’ll be corresponding with in 2020, when the grant money goes fully into effect. In traditional Conwell fashion, everyone appears to be a long-lost friend, everyone receives a back pat or felt handshake. It’s clear why fellow councilmember Blaine Griffin amiably refers to Conwell as the “Mayor of Glenville.”

Mayor Frank Jackson stands with Joseph Galvan, regional administrator of the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development, and Kevin Conwell, Ward 9 councilman, to receive a check for $9.7 million for Cleveland’s lead crisis.After the check-holding photo-op, Conwell sticks around the Red Room to greet members of HUD he’ll be corresponding with in 2020, when the grant money goes fully into effect. In traditional Conwell fashion, everyone appears to be a long-lost friend, everyone receives a back pat or felt handshake. It’s clear why fellow councilmember Blaine Griffin amiably refers to Conwell as the “Mayor of Glenville.”

When asked how he will ensure the new grant money is funneled appropriately and accurately into his ward, Conwell says he himself will be “following the goals and objectives” directed by HUD, engaging in monthly meetings with HUD Field Director Pam Ashby, along with Manesse herself.

And for meeting residents at their level, Conwell says he himself will need to “show leadership” and be his own boots on the ground.

In his own words: “If the mountain won’t come to Muhammad,” he says, “then Muhammad must go to the mountain.”

Calls To Action

Volunteer as a door-to-door canvasser for Environmental Health Watch’s on-the-ground Action Team.

Apply to be one of the 14 future community engagement specialists to start in early 2020.

Call the Cleveland Department of Public Health hotline at 216-263-LEAD, to find out more information about proper lead risk assessment.

This article is part of our "CLE Means We: Advancing Equity & Inclusion in Cleveland" dedicated series, presented in partnership with Jumpstart, Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership/The Commission on Economic Inclusion, YWCA of Greater Cleveland, and the Fund for Our Economic Future.