Clark-Fulton is a known food desert. Can new health initiatives change the way a neighborhood eats?

The swollen joints and high fevers started sometime before Patty Esparza moved out of El Paso. She’d been living with her husband and son José for years, working as a healthcare liaison for the Mexican Consulate, traveling across the border to Juaréz to visit her mother.

Then, the pain began, and Esparza was diagnosed with lupus. Harassment from Chihuahuan gangs pushed the Esparza family to Cleveland, where, in June 2011, Esparza finally began two years of kidney dialysis.

“I was very sick,” she says, sitting in a small office cubicle at the Spanish-American Committee, where she works part-time. “My kidneys didn’t work. I was scared, but I knew we had to do something.”

“I was very sick,” she says, sitting in a small office cubicle at the Spanish-American Committee, where she works part-time. “My kidneys didn’t work. I was scared, but I knew we had to do something.”

University Hospitals doctors told Esparza she needed a kidney transplant. Fortunately, the Esparzas were insured: two years of hemodialysis and her 2013 operation cost roughly $500,000. Then came the anti-rejection drugs—about $2,500 a month—along with the psychological effects of high blood pressure and weight gain.

Through all this, Esparza kept a family mantra in mind: Si no tienes salud, no tienes nada. Without your health, you’ve got nothing.

With Hispanic-Americans almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than non-Hispanic whites, reaching the Hispanic community seems requisite for local healthcare providers. In Clark-Fulton—which is roughly 40 percent Hispanic—food ministries and healthcare coaches are actively engaging in specialized efforts to not only provide low-cost services, but prevent such diseases in the first place.

Esparza is among their ranks as the head of the Northeast Ohio branch of La Ventanilla de Salud (“Window of Health”), a healthcare referral service bankrolled by the Mexican government. She hosts free screenings every final Wednesday of the month at the Spanish-American Committee, where EMS personnel administer blood pressure readings and three-minute finger-prick tests for diabetes. On other days, Esparza drives an hour to Lorain or Painesville—cities dense with Mexican immigrants—to set up “Mobile Consulate” stands at local events.

Esparza believes La Ventanilla de Salud's presence is much-needed due to the misconstrued skepticism of doctors she finds in the Latino community.

Esparza believes La Ventanilla de Salud's presence is much-needed due to the misconstrued skepticism of doctors she finds in the Latino community.

“La gente no quiere ir,” she says. “They only go to doctors for serious conditions, [and] others just rely on home remedies. But I tell them, ‘What if what you have is more serious than you think?’”

Creating an oasis

In the Cuyahoga County Board of Health’s 2017 “Supermarket Access Assessment” study, it was found that nearly half of Clark-Fulton lives in a “distressed” food-desert area—signifying low vehicle access and high poverty—with roughly 60 percent of the neighborhood focus area 0.6 to two miles away from the nearest major grocery chain (the Save-A-Lot on Clark Ave. and West 30th St.). With half of Clark-Fulton’s residents under the poverty line, a $300 monthly grocery bill isn’t just implausible. It’s pretty much unthinkable.

“Hey, food’s expensive,” says Stan Sifers, founder of CityReach Church on 38th and Clark. “And I know I like to have more choices in my life than Save-A-Lot or a Family Dollar.”

Sifers, the former owner of a food ministry in Arizona, started ramping up his produce giveaways after monthly events started to bring in over 100 families a week. With grant assistance from the Greater Cleveland Food Bank, Sifers is able to “fill in the gaps” in a health-conscious, curated manner.

Most of the food Sifers offers—pastas, zucchinis, chicken legs, and fresh soups—is not only given out without quotas to attendees shame-free (“It’s not a hand out, but a hand up,” he says), but also accompanied by a package Sifers believes is of utmost importance: organic recipes along with a stocked-full grocery bag.

“Maybe 10 percent of [attendees] don’t know how to cook squash, let alone eat it,” he says. “Sure, good food is expensive. But as far as cooking goes? Most people just don’t know in the first place.”

"More than just our diets"

they made Hispanic cuisine—and gravely change their lifestyles.

they made Hispanic cuisine—and gravely change their lifestyles.

After two and a half months, Ramos was floored.

“Their blood pressure dropped,” she says. “There was a 50-pound weight loss collectively. It was absolutely beautiful.”

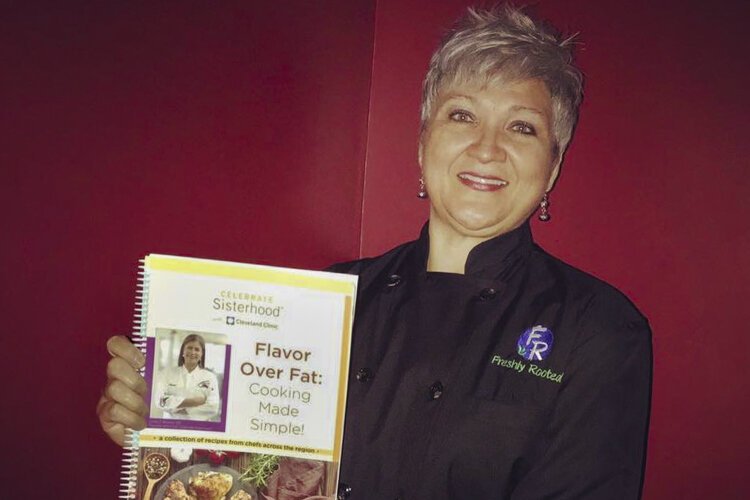

Ramos says it's little wonder that the Latino community suffers from diabetes and obesity considering the starchy, high-fat nature of many favorite foods. A professional chef with Puerto Rican background, Ramos first assumed what she calls a "conscious awareness" about Hispanic cooking after seeing depressing statistics about heart disease from the Cuyahoga County Health Department.

She knew the age-old empanadillas recipes from the island had to go—science beckoned for a re-evaluation of tradition, or as Ramos says, "[willingness to] look at what your blood is saying versus what your grandmother did in the kitchen.”

She knew the age-old empanadillas recipes from the island had to go—science beckoned for a re-evaluation of tradition, or as Ramos says, "[willingness to] look at what your blood is saying versus what your grandmother did in the kitchen.”

VIDA!’s popularity helped fuel MetroHealth’s decision to open the "Food as Medicine Clinic" in Outpatient Care last September, a fully-stocked pantry of produce and dry goods—currently in its pilot stage—that supplies 100 enrollees with monthly groceries. Director Jennifer Bier says the food pharmacy acts as a “stopgap measure for people who simply don’t have enough access to food.”

Banking on the food ministry

It was about two decades after kicking his drug addiction and ending a 13-month prison sentence when Henry Flonnoy decided to become a pastor. He’d lived most of his life on Cleveland’s east side and founded Drama Free Ministries in Clark-Fulton after meeting his wife Junia.

Over the next five years, Flonnoy witnessed a growing concern in the neighborhood: more and more residents were going day-to-day without sufficient resources.

“People don’t start seeking help until they’re desperate,” says Flonnoy, who also works as a drug dependency specialist. “As far as that goes, you can say I’ve heard it all.”

Like many other ministries, Flonnoy began setting up a 10-foot by 10-foot tent on one Sunday per month, offering those in need fresh fruit and vegetables, backpacks, and kids’ socks and shoes. No ID or excuse was needed, “just name and contact information.”

Like many other ministries, Flonnoy began setting up a 10-foot by 10-foot tent on one Sunday per month, offering those in need fresh fruit and vegetables, backpacks, and kids’ socks and shoes. No ID or excuse was needed, “just name and contact information.”

In 2018, Flonnoy contacted newly elected councilwoman Jasmin Santana to see if she could help ramp up food offerings at Drama Free Ministries. She responded by awarding Flonnoy a $1,500 grant to help buy equipment and supplies for the ministry’s pantry expansion project. (Flonnoy’s construction company is covering the $10,000 build-out.)

“This screams to me that she needs help,” Flonnoy says. “And that we can be a part of her voice.”

According to Junia Flonnoy, they plan to open the hot food pantry in September, and Drama Free Ministries will also be hosting a one-day health clinic with free blood pressure screenings and diabetes checks as the first of what the Flonnoys hope will be many free health-centric community events.

It's all part of a bigger push to empower and educate Clark-Fulton residents around better health from all angles. Says Ramos, “This is bigger than food access, more than just our diets. It’s a community working together for the health and wellness of its people.”

This article is part of our On the Ground - La Villa Hispana community reporting project in partnership with Dollar Bank, Hispanic Business Center, Esperanza Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, and Cleveland Development Advisors. Read the rest of our coverage here.