Safety first: How Hispanic police officers and residents are ensuring a safer Clark-Fulton

For decades, the Mercedarian Walkers met regularly for Wednesday walks throughout Cleveland's Clark-Fulton neighborhood. The group of seniors has become well-known in the neighborhood for their promotion of healthy lifestyles and advocacy for issues facing Hispanic seniors. But over the last four years, the group of 14 members has dwindled to about four or five people, and the walks happen less often.

According to 71-year-old group leader Esperanza Barillas, the decision to cut back on their club’s regular routines stems both from members’ declining health and a growing sense of uncertainty about safety in Clark-Fulton.

“For us, it’s too dangerous,” Barillas shares, sitting in the lobby of the Mercedarian Plaza Senior Complex, flanked by two other caminadores.“We’re no longer the group we were four years ago. But there’s not much we can do. No hay pasado la policia.We just don’t see enough police.”

The Hispanic Police Officers Association (HPOA) is trying to change that—and thanks to recent developments, they’ll soon be more equipped than ever to do so. In July, two HPOA officers were reassigned to focus exclusively on HPOA full-time, which will be a huge boon for the eight-officer team.

"Now we'll be able to dedicate more time to the mission of the association," says HPOA vice president Emmanuel “Manny” Velez, one of the two dedicated officers along with HPOA president Edwin Cuadra. (Velez previously split his time between the HPOA and being a Cleveland Police Department sergeant.) "We were the only association within the division that didn't have that privilege in the past."

"Now we'll be able to dedicate more time to the mission of the association," says HPOA vice president Emmanuel “Manny” Velez, one of the two dedicated officers along with HPOA president Edwin Cuadra. (Velez previously split his time between the HPOA and being a Cleveland Police Department sergeant.) "We were the only association within the division that didn't have that privilege in the past."

Velez hopes that the HPOA will also soon receive more resources toward addressing a bigger need: providing Spanish-speaking officers in times of crisis. According to Velez, there aren’t enough officers in Cleveland to respond to 911 calls in which the callers don’t speak English. He plans to use his new position to assist the division in recruiting within the Hispanic community.

“It’s all about that language barrier,” says Velez. “We’ll get a call saying, ‘Hey, I need a Spanish-speaking officer here.’ And the officers that do respond to that call do so without getting extra pay.”

As HPOA increases its presence, Velez hopes he and his fellow officer-liaisons—all of them bilingual—can turn back unsafe perceptions of the neighborhood, a sense he says that all starts with increased police presence, “just seeing a familiar face, whether in plainclothes or in uniform.”

Meet Velez and other local heroes working hard to restore a sense of safety in Clark-Fulton.

Staying connected

Over on Clark Avenue, Maisa Iwais, 37, who co-owns the Fli High Smoke Shop with her husband, Mohammad, says that her store has experienced three break-in attempts since last September. A native of Clark-Fulton—Iwais’ father used to own a car wash down the street—Iwais and her husband have since doubled down on store security, barring their windows and equipping Maisa with pepper spray.

“It was never like this back in the day,” Iwais says, sitting in the front of her shop, second to the Iwais’ storefront in Parma Heights.

But Iwais says she has generally been pleased with the police follow-ups after each incident, and that a neighborhood watch rep visited her upon opening. According to Metro West Development Corporation’s community involvement director Adam Gifford, three neighborhood watch groups in Clark-Fulton “meet at varying levels of activity.”

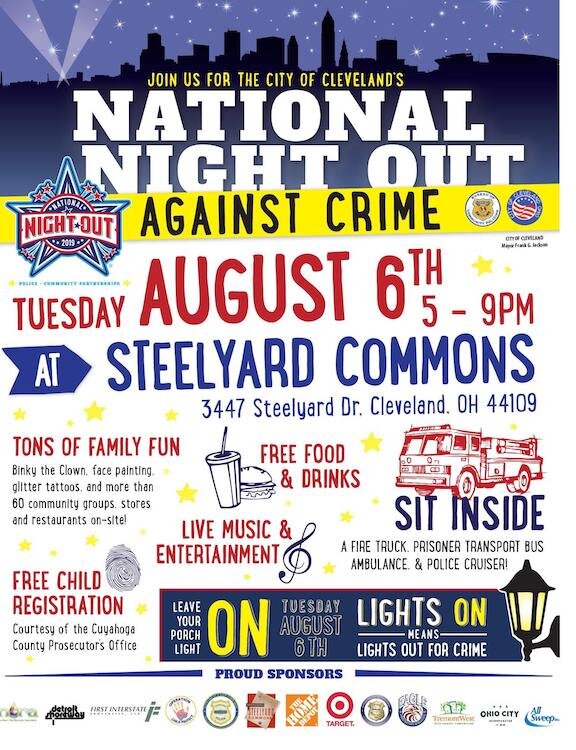

According to Gifford, Metro West’s neighborhood safety committee has hosted several “Cookouts with Cops” annually in recent years, and he also points to the monthly Second District Community Relations Committee (SDCRC) meetings as an effective means for police and citizens to connect. On Tuesday, Aug. 6, the SDCRC held a family-friendly “National Night Out Against Crime” event at Steelyard Commons, in which kids could sit inside fire trucks, prisoner transport buses, and police cruisers.

According to Gifford, Metro West’s neighborhood safety committee has hosted several “Cookouts with Cops” annually in recent years, and he also points to the monthly Second District Community Relations Committee (SDCRC) meetings as an effective means for police and citizens to connect. On Tuesday, Aug. 6, the SDCRC held a family-friendly “National Night Out Against Crime” event at Steelyard Commons, in which kids could sit inside fire trucks, prisoner transport buses, and police cruisers.

Gifford believes all of these efforts are integral to helping residents feel safe and secure in their surroundings—as well as gaining the faith of and attracting new residents at a pivotal time of neighborhood transformation. “People’s perception of safety could affect their confidence, even if it’s not necessarily reflective of what the reality is,” says Gifford. “Perceived safety issues have an effect on investment in properties.”

Ensuring accountability

Angelo Ortiz also has a vested interest in a safer Clark-Fulton, having lived in the area since he was 18 years old. Ortiz has been involved in Clark-Fulton crime prevention since his cousin Walter "Wally" Rivera died at 48 on a fentanyl overdose in 2014. Then, 24-year-old Giovanni Ramos, a friend of a friend of Ortiz’s, was shot and killed.

After a shooting took place outside of Club Alma Yaucana on April 22, Ortiz saw the incident as representative of a bigger issue. “It used to be that kids would knuckle up and fight, then become friends after. Now, young bucks just start shooting. They don’t play around,” says Ortiz.

Hoping to create a brighter future for his grandchildren, Ortiz partnered with José Reyes, a pastor at the Iglesia Nueva Vida, to respond to the Alma Yaucana shooting in a dire, nonviolent fashion. The result was a 30-person “Stop The Violence” march with Nayeli Negrón (Miss Latina Image’s 2018 winner) down Clark Avenue; Ortiz says the event went so well, he’s going to host a second in August.

As the radio host of “La Ruta del Sabor,” a Saturday program on WCSB 89.5 FM, Ortiz says he always caps his show off (in Spanish and English) with recent crime recaps of late. And more importantly, to speak up before they make news.

“I say, ‘It’s not about you being a snitch,’” he says. “If you see something, say something. If we don’t clean up the neighborhood now, then when?”

The same consciousness regarding Clark-Fulton’s struggles is well-known to the CDCs and City Council reps who work, live, and drive through the neighborhood regularly. Just as it is for Velez, the issue is strikingly similar at a political level: Division among neighbors is a detriment to preventing crime; unity is paramount to solving it.

“We’re so involved in our own worlds, it’s hard to go outside of it,” says Jasmin Santana, councilwoman of Ward 14, which includes the Clark-Fulton community. “We can’t just blame the police. We have to all be accountable, too.”

After a year and a half in office, Santana says she’s not only become privy to issues facing her ward—illegal dumping, petty theft, heroin use—but also the intricate complications involved in resolving such issues. It’s why Santana says she’s doubled down on social media and routine canvassing, along with advocating for a possible rec center in Clark-Fulton.

As for ramping up police presence (which Santana admits is low), she urges local folks to begin taking the reins themselves.

“We’ll get calls like, ‘Hey, there’s this drug house, it’s been there for five years,’” Santana says. “And I’ll say, ‘So, have you ever called police?’ ‘No!’ ‘Well, why not?’ That’s what our office is here for.”

Hispanic Police Officers Association outreach event at Primera Iglesia BautistaConnecting with youth

Hispanic Police Officers Association outreach event at Primera Iglesia BautistaConnecting with youth

On a recent Friday morning in July, Velez, Cuadra and two officers in HPOA, José Torres and Angily Gaviria, visit the Primera Iglesia Bautista Hispana for a routine meet-and-greet with 50 kids ages five to 15. Both Velez and Cuadra show up in high spirits despite their unrelenting schedule: besides HPOA’s full-time duties, this year, they recently spearheaded the annual Puerto Rican Day Parade, a $34,000 endeavor neither administrator got paid for.

“We’re blessed to know him,” says Maria Lourdes Cabán, director of the Primera Iglesia, as Velez shakes hands nearby in full uniform with Cabán’s kitchen staff. “He’s a very gifted man. Very loving. He’s the perfect person for the job.”

For about an hour, Velez and company speak to the 50 kids as they sit in the Iglesia’s pews, listening to the three officers, save for Cuadra, brief them on anti-crime procedures that could save their lives.

“How many of you guys know that the police [officer] is your friend?” Velez says amiably. About three quarters raise their hands. Velez and company continue, riffing on everything from cigarettes to kidnapping.

“Do we know what to do if we see a gun?” asks Velez.

“Like a Nerf gun?” one kid says.

“Get an adult?” another says.

“Call 911!” a third shouts.

“Good, guys,” Velez says. “You guys know you can call us."

About an hour into the meet-and-greet, Velez divides the room into two, giving half to him and Cuadra (the only one present in plainclothes), and the other to Torres and Gaviria.

With Cuadra standing behind him, Velez sits in the pews for a personal heart-to-heart, entertaining “any question you guys want to ask me.” He fields a tough load of insight into Clark-Fulton’s youth: a 14-year-old who repeatedly had his bikes stolen by a local gang, another who witnessed his father get arrested on drug charges. Throughout the talk, Velez maintains his ears-open demeanor, telling the kids through his straight, unwavering tone: This is how things are, but we are here to lessen the burden.

“It’s important that we all make good decisions in life,” he said to end his speech. “One of the things I want you to get when you walk away from this is that you know us. That when you see an officer on the street, or wherever, you think of me."

This article is part of our On the Ground - La Villa Hispana community reporting project in partnership with Dollar Bank, Hispanic Business Center, Esperanza Inc., Greater Cleveland Partnership, Cleveland Neighborhood Progress, and Cleveland Development Advisors. Read the rest of our coverage here.