The art of papermaking is alive and well at Morgan Conservatory

In an 80-year-old former machine shop on the eastern edge of Midtown, Morgan Conservatory is preserving the ancient art of papermaking on Cleveland's east side. One of only about 20 studios of its kind in the country, the papermaking studio is celebrating its 10th anniversary—and its intrepid team is still learning new things every day.

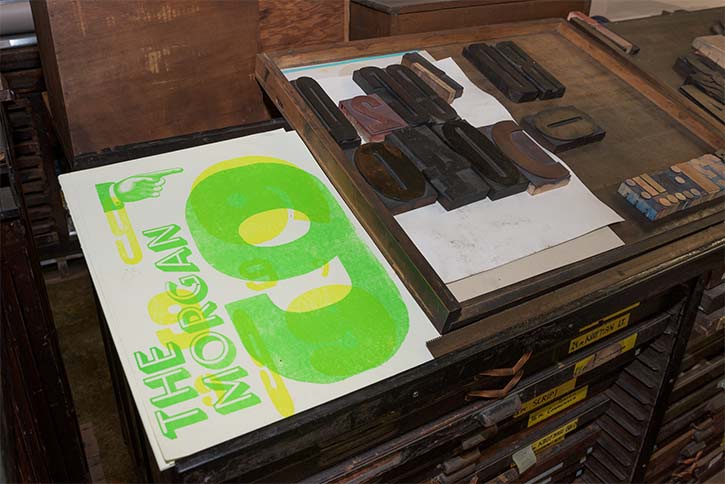

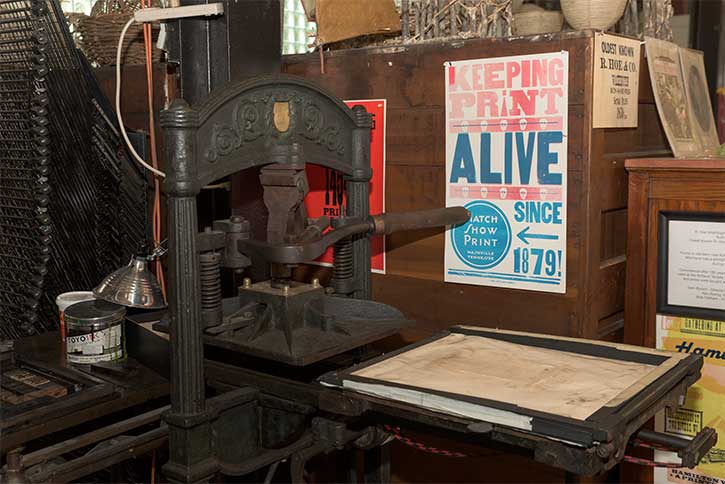

“You go into the process knowing that you might not get what you’re hoping for,” Allie Morris, an intern from Xavier University, says as she prints on fresh paper using a letterpress. Around her, a half-dozen botched pieces are strewn. “All of this is the beginning of print,” she adds. “I like knowing what I do has a foundation in it. I guess we’re embracing the past.”

The "past" is a colorful and rich one, indeed. Long before the West sprouted the printing press, an enterprising Chinese eunuch named Cai Lun began experimenting with materials including tree bark, fish nets, old rags and hemp waste to produce the first paper in 105 CE. Lun’s brainchild spread to Islamic nations in the 8th century, then to Europe in the 11th, when medieval paper mills churned out reams powered mainly by river water.

Paper, as we know it, was born.

As industrialization beefed up the mills, Lun’s concept—gleaned from observing paper wasps make their nests—remained simple: felted sheets of pressed fiber laid in water, dried and matted. As many craft papermakers might say: Remove the complexity, you have the art.

As industrialization beefed up the mills, Lun’s concept—gleaned from observing paper wasps make their nests—remained simple: felted sheets of pressed fiber laid in water, dried and matted. As many craft papermakers might say: Remove the complexity, you have the art.

Though antiquated, Lun’s approach is still practiced sparingly throughout the States—making Morgan Conservatory part of a select group keeping the art alive. Spacious, tranquil and open to all, Morgan is a niche artist’s dream: 15,000 square feet of throwback art production in three studios (from a print room with century-old iron letterpresses to a full book bindery and gallery). The prime attraction? A two-room “wet studio” covering every stage of paper construction: boiling fibers (such as hemp, denim, cotton), pulping it in one of three beaters, and then pulling sheets using a mold and deckle.

It's a process that Morgan Conservatory has refined over its decade in business, which has its own interesting origins. The papermaking venture began with an octogenarian financial manager and art collector named Charles Morgan and his ceramicist protege named Tom Balbo. Balbo graduated from Syracuse University in 1980 with a heart set on using paper as the artistic medium; after graduation, he relocated to Cleveland to find studio space. For the next three decades, Balbo worked the nationwide “craft circuit” as a potter, while experimenting with the niche medium he'd first encountered at Syracuse.

Morgan was intrigued. Come 2006, the retired collector—who was losing his vision and mobility—decided to put his savings toward funding a worthwhile creative pursuit. He called upon his main caretaker, Balbo, who was coincidentally aspiring to teach.

“[Morgan] said, ‘My intent is whatever you decide,’” recalls Balbo, a soft-spoken 61-year-old clad in T-shirt and Nikes. He's sitting in the Conservatory’s Caraboolad Garden, the largest U.S. grove of Japanese kozo (the Eastern bast fiber from paper mulberry tree bark, thought to be one of Cai Lun's choice materials). “I could have done pottery. I could have done whatever. But he saw my interest in papermaking, and we went with that.”

In late 2006, Balbo began hunting for warehouse space on Cleveland’s east side with the help of Morgan’s endowment. Optimistic about the east Midtown spot, Balbo went “gung ho” and put in all his earnings to renovate the dormant machine shop into a papermaking mecca—spending $500,000 on insulation and $150,000 on window treatments and roof drains. In 2007, the Conservatory held its first open house with a distinct mission: to provide Northeast Ohio paper artists a refuge when most art schools had begun minimizing—or even eliminating—programs that fostered the pulping craft.

For his part, Morgan was delighted. “It was a wonderful experience for Mr. Morgan,” Balbo says of that first open house. “That’s why I named it after him. Without his endowment, I couldn’t have done all of this at this scale.” On August 5, 2009, a year after the Conservatory officially opened, Morgan died at the age of 98 years old.

Today, as the Conservatory marks its 10-year anniversary, the studio operates pretty much without pause. Balbo and his staff run not only a full paper operation, but also an on-site store carrying everything from denim bound books to 6-by-8-inch kozo canvas to marbled dyed sheets. (The Conservatory's paper creations are also carried at Cleveland Museum of Art, MIT and the Frick Collection in Manhattan.)

Balbo's focus is primarily on preservation, and he performs exhaustive outreach to keep neophyte artists involved with the craft. His goals include buying a nearby building for artist residencies and holding 10-week workshops for area high school students. Other ideas include solar panels, a roof garden, a library of paper-centric materials—anything to keep the Conservatory in business.

As Balbo turns 62, the veteran craftsman seeks to slowly inch away from his institutional post and ease back into the art himself. Although he’s cognizant of authentic papermaking’s ever-decreasing presence globally, Balbo’s self-assured that the Conservatory will always have value in an art world dominated by digital.

“Maybe it’s selfish, because I love the craft so much,” he says with a laugh. “But I mean, we’ve grown accustomed to paper for 2,000 years now. People still want that hand[written] invitation in the mail. That letter they can touch. Something to show there’s still a sense of humanity.”